Remembering The Maroon’s first female Editor in Chief

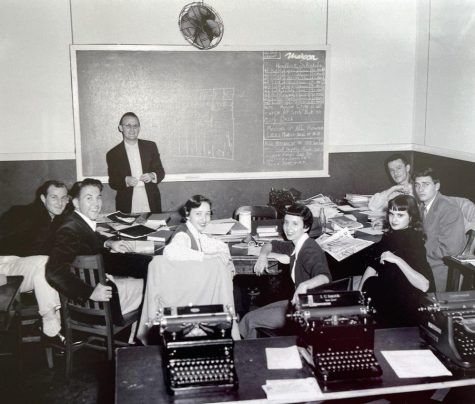

Shirley Rhode and John Nicosia stand holding an issue of The Maroon in 1954. The two served as editors in chief of The Maroon during that year, which made Rhode the first woman to hold that position.

December 26, 2022

During the final line of Glenda Rhode Pausina’s eulogy for her mother, Shirley Rhode, her voice began to quiver with emotion.

“Heaven is a happier place now, for her smile is there. I love you mother dear. Your eldest, Glenda,” she said.

Christmas day, Dec. 25, marked the one month anniversary of Shirley Rhode’s passing.

Sixty-eight years earlier, Shirley Rhode had been the first female editor in chief of The Maroon. While it had been a major accomplishment, it was only the beginning.

“Those 87 years she lived on this Earth, she truly made a difference in so many people’s lives,” Rhode-Pausina said.

Attending Loyola

Shirley Rhode had graduated Cum Laude from Dominican High School, and was offered a full-ride scholarship to Dominican College, Rhode-Pausina said.

“She said ‘no thank you’ because she wanted to meet a husband. She didn’t want to go to an all-girl university,” Rhode-Pausina said.

Shirley Rhode instead attended Loyola University in New Orleans where she majored in Journalism.

Tootsie Williams, also a journalism major of the same year, met Shirley Rhode in college, and the two started a friendship in school that lasted for 70 years, Williams said.

“She taught me how to be disciplined,” Williams said. “I really credited her with that, though, because she was like the little mother.“

While the two attended many of the same classes, they also both became involved in The Maroon at Loyola.

The Maroon

Shirley Rhode served as Co-Editor with John Nicosia in 1954, and then served as the Executive Editor on her own in 1955. She was the first female Editor in Chief of The Maroon just two years after Loyola began to formally admit women into the college of arts and sciences.

Williams said this was a time when a lot more women began to attend the university.

Rhode-Pausina said gender barriers were never something that stopped Shirley Rhode.

“I can never remember a time when my mom was hesitant,” she said. “She just marched straight forward.”

As an editor, Shirley Rhode was disciplined as usual, and tough on deadlines, said Williams.

During her time as Editor in Chief, the paper won the national award for excellence.

Even as The Maroon’s leader, she never stopped displaying her sense of humor and wit.

Shirley Rhode said in a memoir that she wrote a column for The Maroon called “Steppin with Stoma,” with Stoma being her maiden name, that made waves on campus.

“I got teased unmercifully for writing about one of the fraternity boys and his little organ,” she wrote. “It was truly an organ, you know, the musical kind, but that didn’t stop the teasing.”

Shirley and George

Amidst exploring her love for journalism while at Loyola, Rhode-Pausina said Shirley Rhode also met the love of her life, George Rhode III.

At the time, the two also worked at The Maroon, where Shirley Rhode was the Associate Editor and George Rhode III was Sports Editor.

The two weren’t good at hiding their growing feelings, Williams said.

“Shirley and George tried to keep it a secret that they were falling in love,” she said. “They didn’t want anybody to know at The Maroon office, so they would try and pretend that they didn’t even know each other. Then you would see them holding hands around the campus.”

George Rhode III was a veteran who was attending university as part of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, which offered various benefits to returning war veterans, including funding for college. He planned to make a career out of the military, Rhode-Pausina said, which was an idea he abandoned after meeting Shirley Rhode.

“I know soulmates is an overused term, but they were truly like that,” Rhode-Pausina said. “They were each other’s biggest champions, and in turn they were their children’s biggest champions.”

Shirley wrote in her memoir, “graduation night was anticlimactic. The night before, I hosted a Maroon-Thespian party in my backyard, a crawfish boil. We (Shirley and George Rhode) snuck away for a few minutes to be alone on my front porch. And that’s when he gave me my engagement ring.”

Shirley Rhode sat in the front row at the convocation the next day as she graduated Cum Laude, she wrote.

“I made sure the light caught my ring,” she said.

The Seven Gs

Shirley Rhode continued to work at the New Orleans States after graduation, which she started during her senior year at Loyola, said Rhode-Pausina. The New Orleans States was one of the two afternoon papers in the city at the time. Shirley Rhode served as the religion editor and a general assignment reporter.

That was where she worked until she gave birth to Rhode-Pausina, and stayed home until the youngest child, Gretchen Rhode, was in kindergarten.

George and Shirley Rhode had seven children in less than eight years with no twins. All of their children had names starting with g: Glenda Rhode-Pausina, George Rhode IV, Gayle Rhode, Glynis Rhode Nacozy, Gardere Rhode, Geoffrey Rhode, and Gretchen Rhode.

“We are her beloved seven g’s, and she was so proud of us all,” Rhode-Pausina said.

Williams said Shirley Rhode was an incredible mother.

“She managed her eight children extremely well, she and George,” Williams said. “Her children are just sweet, loving. All of them.”

Shirley Rhode and George Rhode III originally wanted to have 12 children before they settled for seven. Shirley Rhode was an only child, and George Rhode III had one sibling, which is why Rhode-Pausina said the two had wanted such a big family.

“They were real emphatic that we grow up close, and that we would always be there for one another, and even after they were both gone,” Rhode-Pausina said. “We’re all truly one another’s best friend, and we still hangout. They raised a really close, loving family.”

A welcoming home

They also built a welcoming family, Rhode-Pausina said.

“Our home was always the home where everybody hungout. And so many friends who didn’t have the best of parenting in their homes always gravitated to mom,” she said. “There was never anyone I can remember in my life, and I’m almost 65, who didn’t like my mom.”

When it came to her daughters, Shirley Rhode raised them to not let their gender stop them from achieving their full potential, Rhode-Pausina said.

“Mom taught us daughters to always stand up for ourselves, never disparaging men but letting us know we were every bit as good as (them),” she said. “That’s something very empowering to get from your mom in the 60s and 70s, because not a lot of moms were teaching that back then.”

Rhode-Pausina said her mother wasn’t a prejudiced person, and taught her children that through leading by example.

While Shirley Rhode was the Girl Scout leader for Gayle Rhode’s troop at Saint Frances Cabrini school, she took three Black girls into the troop, making them the first Black children allowed to join.

“Three or four girls pulled out of the troop because of that,” Rhode-Pausina said. “Mom was so courageous because to her, she wasn’t doing it because it was a big deal. Three kids wanted to be in a troop.”

Lasting legacy

When Shirley Rhode went back to work after her youngest daughter started school, she worked as an executive assistant at an insurance agency for quite some time, Rhode-Pausina said. That was before she switched to doing restaurant books for various establishments before the Rhode family began to start up their own restaurants, she said.

George Rhode III and his son, George Rhode IV, had started the Olde N’awlins Cookery in 1984, which Rhode-Pausina said is still operating downtown. The family eventually went on to open George IV in 1985, and Georgios in the early 90s.

Georgios was opened around the time when George Rhode III and Shirley Rhode retired in Mississippi. For a while, Shirley Rhode worked at banks, which Rhode-Pausina said was because Shirley Rhode couldn’t just be retired.

Eventually the couple moved back to New Orleans to be with family around 15 years ago, she said.

“They were true New Orleanians their whole life. They loved New Orleans. They were very proud of New Orleans,” Rhode-Pausina said.

The couple had founded the Press Club of New Orleans, and were founding members of the Gridiron Show, a part of the Press Club which puts on shows that satirize current events and headlines.

Shirley Rhode would write parodies for the Gridiron Show, Rhode-Pausina said.

“She would take a song, like ‘there is nothing like a dame,’ and mom would change it into something like ‘there is nothing like campaigns,’ and then write the whole song and they did shows for years,” she said.

Writing was always a big part of Shirley Rhode’s life, Rhode-Pausina said.

“She wrote her whole life. She always wrote. She wrote poetry. She would make poems for any occasion,” she said.

Along with writing, Shirley Rhode was an avid reader, Rhode-Pausina said.

“She was extremely smart, and loved to read, and did until the end of her life,” she said. “She read the newspaper every single day. She did both crossword puzzles. She did the sudoku. She did the word jumble. And she was just constantly working her brain.”

Cooking was also a major part of what Shirley Rhode was known for in the family, particularly meshee, an arabic dish made by stuffing grape leaves. Shirley Rhode was 100% Syrian, which is why her family often referred to her as sitty, the Arabic word for grandmother, Rhode-Pausina said.

Shirley Rhode’s recipes, Rhode-Pausina said, have since become something that the family passes down from generation to generation. As a family full of chefs, food has always been a big part of the family, she said.

“That’s kind of something mom has always been the center of,” she said.

While the death of George Rhode III in 2017 was hard on Shirley Rhode, the COVID-19 pandemic is when Rhode-Pausina said she started to truly see her mother’s decline.

“She just started getting a little forgetful, and then it just started escalating because we did the same thing every day for so long,” she said. “But even during all that time, she was still just the best mom in the whole world. She loved to go anywhere. We called her FOMO, fear of missing out, because she always wanted to be right in the middle of us. If she was with five of her children, she wanted to know where the other two were.”

Despite whatever health complications came up for Shirley Rhode over the years, Rhode-Pausina said her mother never let it stop her.

“She just loved life. She dressed up for Mardi Gras. Even when we couldn’t go to Mardi Gras for COVID, she put her purple, green, and gold wig on, and her mardi gras shirt, and her big necklace,” she said. “She was just so present. That’s the perfect word for Mom. She was always so there. You never had any doubt that Sitty was in your life. That’s the weird part now because when someone’s like that, they’re so present, and then all of a sudden they’re gone, it makes it even harder.”

Her passing

When Shirley passed the day after Thanksgiving, Rhode-Pausina said she was glad that her mother saw the whole family before her death.

“She was at home with us in hospice for the last couple of weeks. She was in her own bed, in her own room, surrounded by her children and her grandchildren and not in a hospital, which was really wonderful,” she said. “She made our lives so wonderful and so good, and we tried to do that for her in the end.”

Williams said for Shirley Rhode, it’s hard to put to words all that she was.

“It’s not the years that are so important, it’s what the dash represents,” she said, referring to the dash between a birth and death date on tombstones. “It’s just a dash, but if you start to flesh out the dash, so much comes to life. Anyway, that was Shirley. That dash doesn’t even begin to represent what she was.”

Rhode-Pausina said Shirley Rhode was teaching her children all the way until the end.

“She truly taught us how to have a dignified death, how to really be there for your kids all the way until you take your last breath,” she said. “We are so blessed to be her children.”