Phishing scams plague student emails

LUPD Captain Roger Pinac offered students some tips on how to avoid common phishing scams. Photo credit: Emma Ruby

November 7, 2019

Two weeks before school, incoming political science freshman Caroline Budd was baited by a promising email delivered straight to her new university email inbox. The message advertised an internship with an alleged Loyola history professor, and offered considerable sums of money in exchange for simple services, like filing paperwork and running odd jobs.

“Nothing looked out of the ordinary with it,” Budd said. “It was from a gmail account, it wasn’t from a crazy email. The beginning part was set up how the teachers have their emails set up.”

Not doubting the email’s credibility, she contacted the person who emailed her, the “teachers assistant,” and was redirected to the supposed professor.

At 10 p.m. that night, she was ordered to buy office items at Walmart in return for a Google Play card. When she refused, the professor became aggressive, she said. Budd was sent a slew of messages demanding to know where she was, and why she wasn’t doing what she was asked.

It was then that Budd realized something was wrong.

“I looked up the professor’s number on a free web service and it said, ‘warning this number has been known for scams,’” she said. “It said it was a computer generated phone number, so it wasn’t even a real number.”

With that, Budd confronted the scam artist and blocked them immediately.

Even though she recognized the scam before becoming a victim to any consequences, the amount of information they had on her was unsettling, she said.

“They knew my major, they knew I was a freshman coming to campus, so it’s very real how much they knew,” she said.

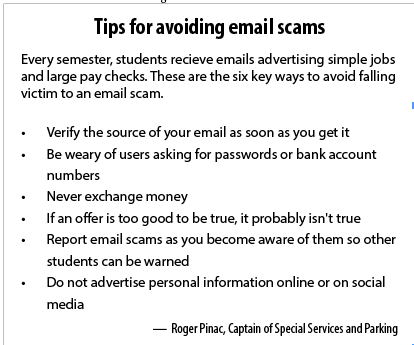

According to Roger Pinac, captain of special services and parking, perpetrators use technology such as mirror websites, the dark web or even valid information like nonprofits to legitimize their scam.

Pinac said students have received emails claiming to be professor’s offering internships before, just as Budd did. To differentiate authentic emails from scams, he stressed verification.

“Anytime someone contacts you, say via email, and you don’t know who they are, verify who they are before you give them any information,” Pinac said.

According to Pinac, students would most likely already know of professors offering valid internships and would be contacted individually before receiving the email, but said that professors are verifiable under the find people tab on Loyola’s website if a name needs to be verified.

Among the Loyola community, the most prominent scams are internships or work-at-home opportunities where students are tasked with depositing checks in their bank accounts,withdrawing a certain amount of money and sending it to other accounts, Pinac said.

In the past, student accounts have been flagged or locked out for depositing invalid checks. A few times those accounts are subsets of a student’s parents, he said.

“Anytime someone asks you for money or tells you get in touch with us, get in touch with (the) university” he said. “The university will never ask students for account numbers or passwords, banks will never ask for account numbers or passwords.”

According to Pinac, the standard regarding pay is “if someone is offering you a deal that’s almost too good to be true, it is.”

“I know it’s difficult,” he said. “Students look for ways to make some money and still be able to go to school. Let’s face it nobody is going to pay you $200 a week to mail a letter for them.”

LUPD encourages students to report scams in order to prevent them from becoming mass baits for students. This year, however, Pinac said there has been a lower number of reports than anticipated. One reason students may not report, Pinac speculates, is because students may be embarrassed to admit they fell for the scam.

Students can make themselves less vulnerable by being mindful of the information they share, Pinac added.

“We live in a social media age obviously,” Pinac said. “You gotta be careful of what you put online.”

While scams continue to circulate in student emails, Pinac assures that the university has a strong firewall against scams, as well as LUPD bulletins on reported scams. The containment of these scams he stressed are contingent on students willingness to report.