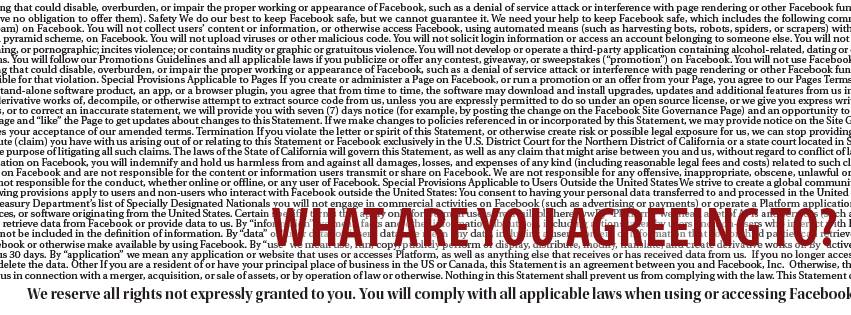

What are you agreeing to?

College students may be relinquishing more rights than they know.

August 28, 2014

Liking, sharing, connecting and communicating — these are the perks that users of the popular social media site Facebook enjoy when creating an online profile.

But before all that, there is one sentence with which every user must comply: “I agree to these terms and conditions.”

The Terms of Service of a site or service outlines what a company, like Facebook, can and cannot do with its users’ content and personal information.

By accepting these terms, users are agreeing to abide by and uphold this contract, regardless of whether they have actually read and understand the terms of service.

However, despite the fact that accepting these terms creates a binding contract, some students admit that they are often too preoccupied with enjoying the perks of their social media profiles to commit to reading the full terms.

“I first signed up for Facebook going into my freshman year of high school,” Kayla Allain, psychology junior, said. “Back then, I was more concerned with having a Facebook page than reading through the terms and conditions. I probably spent more time filling in the ‘About’ section and choosing a profile picture than I did signing up for the site.”

One of the reasons commonly cited for skipping over the Terms of Service is simply the length of the conditions. In fact, Carnegie Mellon researchers recently conducted a study about private policies, concluding that it would take the average American 76 work days to thoroughly read through the privacy policies they encounter in just a year of Internet use.

Alex Kolpan, mass communication sophomore, said that he would rather pass on reading the full Terms of Service than to spend so much time dissecting the terms of a site.

“I hate reading Terms of Agreements and Service,” Kolpan said. “Most of them say the same thing. My PlayStation 3 had over 100 pages of terms — that isn’t going to happen. Getting all my class reading done is hard enough.”

Tedious as the read through might seem, the fact remains that Facebook has the right to access all information provided throughout an individual’s personal profile, just because they are users of the site.

Scott Sternberg, law professor at Loyola, said the majority of this collected information is used for revenue. Sternberg said that the purpose of gathering personal information is to tailor ad presentation to the individual, resulting in more clicks and more revenue for ad clients.

“Facebook, for example, is really just an advertising company,” Sternberg said. “When you agree to their terms and conditions, you allow them to use your information — like your name, age, sex or interests — and this allows you to see targeted ads.”

Kolpan said that he takes care to adjust his privacy settings in order to share only what he chooses; however, he said that he has been using Facebook for 7 years, and cannot remember if he was ever prompted to reaccept the privacy terms after any changes were made to the site’s conditions.

According to Facebook’s terms of service, simply reading through and accepting the terms upon account activation does not necessarily restrict the site’s ability to make further changes.

In fact, Facebook’s terms remind users that the site maintains the right to change its user conditions at any time. These changes, the site reads, are announced seven days prior to implementation on the Facebook Site Governance Page; however, unless a user has ‘liked’ the Page, the updates could go unseen.

Even if a user has not seen the proposed changes within the seven-day period, which allows users the opportunity to comment on the changing conditions, they agree to the new terms by simply continuing to use the site.

The amendments section of Facebook’s privacy laws states, “Your continued use of Facebook following changes to our terms constitutes your acceptance of our amended terms.”

This means that by logging into the site, liking media and continuing to make use of the site’s services, users accept the terms of service as they currently stand, regardless of the terms they first agreed to honor upon joining the site.

“I feel like a change of terms like that should be a bit more direct,” Kolpan said. “It seems sneaky.”

These terms might be enough to deter some users, but others said they benefit from the site in ways that might be permanently lost if they chose to delete their accounts.

Many business professionals strongly advise and even require social media accounts like Facebook and LinkedIn – especially those who want to pursue a career in the communications field.

“Because I have traveled and have made contacts abroad, I like to be able to keep in contact with them,” Maeve Brophy, music industry senior, said. “A lot of times that means keeping my Facebook account.”

Kolpan said that certain aspects of an individual’s personality and presence could permanently be undone by deleting a Facebook profile.

“When you lose Facebook, you lose a sort of separate Internet persona that probably slips into real life more than people think,” Kolpan said.

Whether the pros outweigh the cons, Sternberg said, is a personal choice, but he said caution is necessary when creating an online persona.

“All in all, the best advice is to be careful and be smart with what you post online,” he said. “If you don’t like the contract, you don’t have to sign up.”