To whom it may concern

After a letter from an unconfirmed source is distributed around campus raising concerns about faculty course load, Loyola administrators respond

This letter from an unconfirmed source was distributed around campus raising concerns about faculty course load.

May 1, 2015

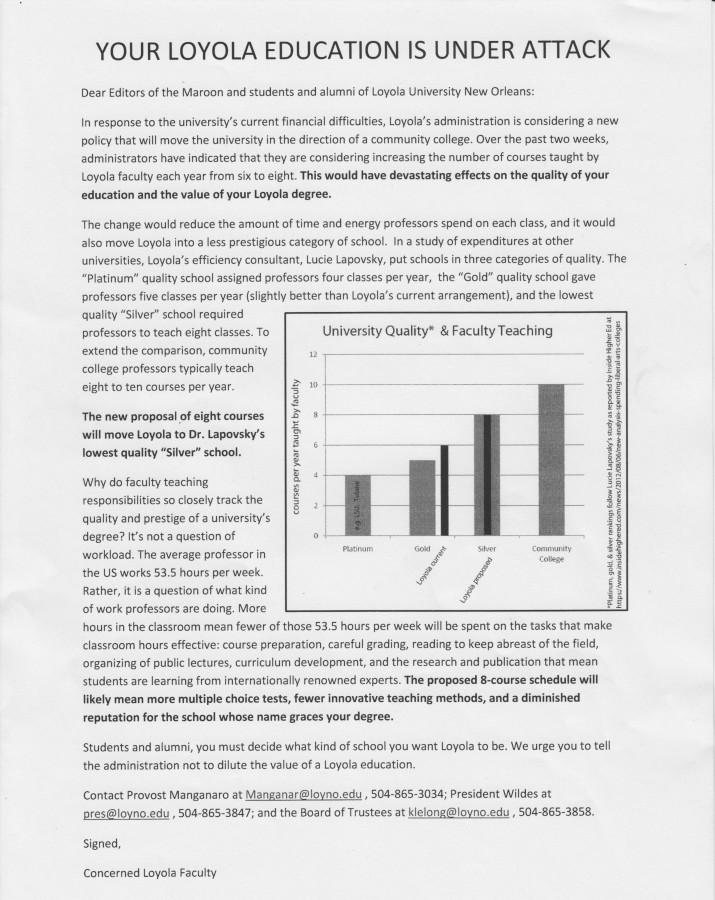

During the week of April 19, a letter emblazoned with the heading “Your Loyola education is under attack” began circulating campus.

The letter, signed “Concerned Loyola Faculty,” claimed that Loyola was considering shifting faculty from teaching six courses per year to eight. When asked if this claim was true, Marc Manganaro, provost and vice president for academic affairs, and Maria Calzada, dean of the College of Humanities and Natural Sciences, simultaneously replied “no.”

“There’s no recommendation at all to go to a generalized four-four teaching load,” Calzada said, referring to a system in which all professors teach four courses per semester.

Calzada is the chairperson of a sub-committee under the Presidential Advisory Group to Develop a Long-Term Financial Equilibrium Plan. Her sub-committee examines faculty workloads and efficiency.

Currently, the faculty handbook states that tenured or tenure track faculty, called ordinary faculty, teach a maximum of four classes per semester, comprised of a maximum of three different courses.

Manganaro said that for several years there has been a provision to release ordinary professors from one course per semester so that they have time to conduct research outside of class.

He and Calzada emphasized that the committee examining faculty workload is considering many different ideas, and that none of these ideas have been finalized.

“I would just caution people not to assume that if there is an idea that one has heard of as something that is being discussed, like for example, having some faculty teach a four-four course load as a possibility, that people not assume that that is a done deal,” Manganaro said.

“Nothing is a done deal,” Calzada replied.

Linda Carroll, a member of the American Association of University Professors’ governing council and Tulane Italian professor, said that any change in faculty course load can raise opposition from faculty members.

Carroll said that there are two main issues with possibly changing the faculty’s workload. The first is that faculty choose to work at universities where the workload aligns with their personal teaching goals. Changing this may cause faculty members to want to leave the university.

“There’s a way in which you would have been attracting faculty to one kind of academic life with one kind of profile, and people have made those choices and built their careers on those choices. At a certain point saying, ‘no, we want something else,’ that could lose you a lot of good faculty members,” Carroll said.

She also stated that faculty members may be concerned that they do not have enough of a voice in the process of making these changes, especially if, like at Loyola, the committee deciding on faculty workload was ultimately appointed by university administrators.

It is ultimately unclear whether the letter distributed around campus was actually written by Loyola faculty members. The letter’s sender set up an email account but could not provide evidence that the Maroon deemed convincing to verify their identities.

Connie Rodriguez, vice chairperson of the university senate, the governing body of the faculty, said that she had nothing to do with the letter.

“What this document says is a flat-out lie,” she said.

She recounted having seen Loyola through two other crises similar to its current financial situation, and that both times the faculty rose to the occasion, even teaching a summer session without pay after having been paid through the semester when Loyola closed for Hurricane Katrina.

“What everybody did in the ‘90s and what everybody did in Katrina was they put their big kid pants on and they took on teaching overloads, and we took on doing extra things to help the university get by,” Rodriguez said.

She stated that should professors leave in the event of a workload increase, Loyola would easily be able to find younger professors to take their places.

“If you think about it, the university could hire one person to take the place of two people who are only getting a two-two load. That’s going to save the university money,” Rodriguez said.

Manganaro said that Calzada’s committee is looking into whether ordinary faculty members are really teaching their three-three course load, along with other concerns such as class sizes, to develop a plan that is equitable for faculty, efficient financially, and ultimately provides the best learning environment possible for students.