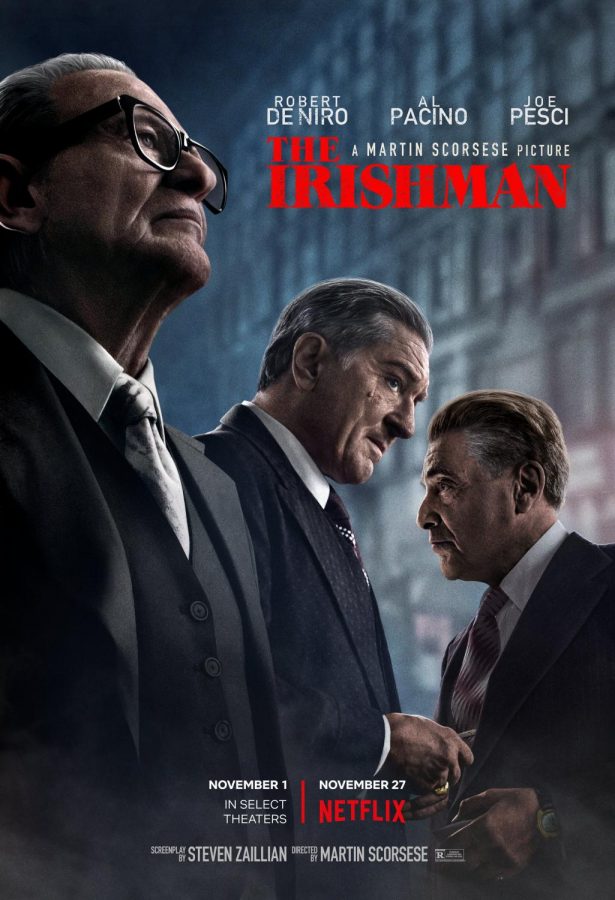

Review: “The Irishman” takes the mob myth to the grave for good

January 2, 2020

Martin Scorsese’s latest crime epic “The Irishman” showcases the celebrated auteur’s usual penchant for gripping spectacle, but this time imbued with worn reflection.

The three-and-a-half hour Netflix film charts the rise and fall of real-life former mob hitman Frank Sheeran, played by Robert De Niro, over the course of the 20th century. As an unreliable narrator (according to crime historians), Sheeran recounts his experiences as a truck driver in Philadelphia during the 1950s, who becomes initiated into a life of crime by capo and eventual mentor Russell Bufalino, played by Joe Pesci. He eventually gets introduced to Al Pacino’s Jimmy Hoffa, who is the powerful president of the Teamsters labor union at the time. Their long and politically fraught friendship shapes history, from the Bay of Pigs invasion to the Kennedy brothers’ crackdown on the labor union. Sheeran eventually wrestles with what to do about Hoffa’s gradual status as a persona non grata within Teamsters as well as the mafia.

A who’s who of crime genre fixtures populate the world of “The Irishman,” some of them having acted in Scorsese’s films before. De Niro excels in his haunting performance as an emotionally distant man, in what is perhaps a culmination of similar roles he has played over the years. Pesci, who came out of retirement after almost a decade, is a far cry from his role in “Goodfellas” as the volatile Tommy DeVito, and all the more menacing for his character’s calm demeanor. Pacino, who amazingly hasn’t worked with Scorsese before, is magnetic as Hoffa; in fact, he makes him come off as Tony Montana’s long lost cousin.

One popular consensus about the shortcomings of “The Irishman” concerns its lack of strong female characters, which are typical of Scorsese’s oeuvre like in “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore” and “Casino.” This ultimately pointless argument is personified in Frank’s daughter Peggy, delightfully played by Lucy Gallina and later Anna Paquin. She may hardly speak a word or two every time she appears on screen, but her silence is effectively conveyed as she looms in the shadows like an accusatory ghost, reminding her father of the weight of the terrible things he had done.

As usual, “The Irishman” is packed with the usual Scorsese hallmarks, from deadpan comedy and sudden bursts of violence to dolly shots and the customary voiceover. They are helped along by dazzling cinematography from Rodrigo Prieto as well as razor sharp editing from Scorsese’s longtime collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker. Meanwhile, one of the talking points about the film is its tricky use of de-aging technology to better illustrate Sheeran and company through the years. They are not necessarily distracting, so it’s best for the viewer to just go with the story.

“The Irishman” is based on the non-fiction book “I Heard You Paint Houses” by Charles Brandt, which features his interviews with the real Sheeran before his death in 2003. The book’s title refers to a euphemism for murder uttered in gangster circles, and is uttered by Hoffa when he first meets Sheeran. Scorsese, as well as screenwriter Steven Zaillian, wastes no time conforming to the book in theorizing about the mafia’s role in several events throughout recent history, from the assassination of JFK to Hoffa’s disappearance in 1975. But he doesn’t necessarily focus on conspiracy theories with the same gusto as Oliver Stone. Instead, he turns to the passage of time to indicate that the universe simply didn’t dwell on whatever these messengers of violence did.

For Scorsese’s latest entry to the crime genre he helped bring into the mainstream, “The Irishman” notably lacks the flash associated with the likes of “Mean Streets”, “Goodfellas”, “Casino” and “The Departed”. In fact, it feels like he is determined to convey the brutal aftermath of violence this time. In fact, most of the gangsters introduced in “The Irishman” get a freeze frame accompanied by the date and manner of their eventual death. For example, Gangster A will get blown up with a nail bomb at his porch in 1981. For all the romanticism associated with menacing figures like Sheeran, Hoffa and Bufalino, the bodies piling up at the end of the day are not a pretty sight.

With “The Irishman,” Scorsese acknowledges his mortality in the same vein as Clint Eastwood, Sergio Leone and Ingmar Bergman. In fact, its last half-hour is devastating in its depiction of old age. It also deals with the age-old question of whether killing someone for the greater good is wrong or a necessary evil. While Scorsese (and by extension Sheeran) doesn’t provide a clean-cut answer, he leaves something for the viewer to think about. While the long runtime may turn some prospective viewers off or think about watching it as a miniseries, it’s all a blur as much as an equally long film like “Avengers: Endgame” was. The film’s use of slow, unhurried momentum ultimately pays off in the long run, as its surviving characters finally face the inevitability of death, not from violence but from isolation.