Tetlow hopes to start funding faculty retirement contributions again

February 3, 2020

Loyola’s decade of financial difficulties has impacted every facet of campus, but perhaps no other faction as significantly as faculty and staff.

Loyola faculty will soon finish their eighth year without a meaningful salary raise or cost of living adjustment, and they are closing in on two years without any university contributions to their retirement funds.

At spring convocation, University President Tania Tetlow told faculty members she hopes the university will be able to start contributing retirement funds retroactively beginning in January should the fiscal year end with the university successfully meeting its balanced budget.

“The faculty and staff have been incredible,” Tetlow said. “But it’s not about what they’re willing to put up with, it’s about what they deserve. And they deserve more.”

If the funds are retroactively contributed, faculty would have lost one-and-a-half years of retirement contributions.

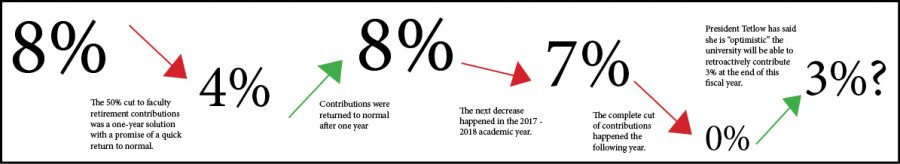

According to music professor Alice Clark, until enrollment misses began to negatively affect university income around 2013, faculty were receiving 8% toward their retirement.

“Eight percent is a lot in some areas, but not higher education,” Clark said.

Clark, who also served as chair of the university senate from 2013 to 2015, said during her tenure as president, those contributions were cut in half to 4% for one year before being raised back to 8%.

The contributions were then decreased to 7% at the start of the 2017 — 2018 school year. Then, as accreditation loomed and a balanced budget was more important than ever, the contributions were cut completely at the start of the 2018 — 2019 academic year.

According to John Lovett, university senate chair, faculty was told the cut was an emergency measure. He said the Board of Trustees passed a resolution that would automatically return the contributions after a year, unless the board passed an additional resolution allowing for its continuance.

At the start of this school year, with the threat of another year of probation hanging over the university, the board did pass a resolution to continue the cuts.

“I understand it,” Lovett said. “I think the faculty were unhappy about it, but they weren’t protesting it as irrational.

While both Lovett and Clark believe Tetlow is serious about returning the contributions to 3%, they both expressed worry at the number.

“My concern is that 3% becomes the new normal, without a promise of restoration to 7%,” Clark said.

In addition to retirement contributions, faculty are also eager to see salary raises and cost of living adjustments.

Lovett said faculty had been receiving steady raises up through 2012, despite the challenging climate created post-Katrina. But the last significant raise happened in 2012.

When it comes to salary raises, Loyola uses a merit-based system, in which the dean of each college is given a pool of money and the discretion to award faculty bonuses. In 2016, Lovett said an across-the-board raise was given that, at the law school, amounted to a 2% salary pool. Lovett said his dean chose to give it to everyone at the law school equally.

“It made sense, because we hadn’t had raises in a long time,” Lovett said.

At Clark’s college, the former college of music and fine arts, Clark said her dean took a different route. He chose to treat the possible raise as a cost of living adjustment, and instead of giving each person the same percentage of a raise, he gave every full-time member of the college the same dollar amount, in order to be as equitable as possible.

“There’s a level of justice to this,” Clark said. “Throughout all of these hard times, there are glimmers of positive things.”

Tetlow said throughout these struggles, the university has been able to keep healthcare costs flat.

“We’ve ended up sort of subsidizing healthcare more and more, so it’s not that benefits have been entirely flat,” Tetlow said.

Still, she said in addition to funding retirement, she is eager to end the wage stagnation and be able to start giving more frequent raises.

The retirement cuts and salary freezes, which happened before Tetlow became president, created a wary air of distrust between faculty and the president, she said. She knew she would have to work hard to overcome those doubts.

“I’ve been extremely careful about being transparent and of rebuilding faith in a place that has gone through lots of transitions,” Tetlow said. “And how critical that work is to honor the sacrifices that this community has made and do right by them.”

The news that Loyola would not be put on another year of financial probation meant everyone could breathe a little easier, according to Tetlow.

“This process required running the university at the same time you had to document running the university, and that latter part took an enormous amount of time, and energy from lots of people,” Tetlow said.

Lovett saw it as an opportunity to start making things right with faculty.

“I think this should give the university administration and board of trustees the confidence to restore the retirement contributions,” Lovett said after the news broke in December.

But while Tetlow is relieved to be off probation, she’s made it clear the hard work isn’t over.

“While I’m so embarrassed to have to ask [faculty and staff] to be patient still…we’re not quite there yet.” Tetlow said.

Despite needing to see the final outcome of this fiscal year, Tetlow has said multiple times she is “optimistic” retirement contributions will be restored.

But Clark isn’t so sure.

“I am hopeful. I have hope,” Clark said. “I’m not ready for optimism yet on this or more things. I need to see more evidence. It’s been a long slog.”