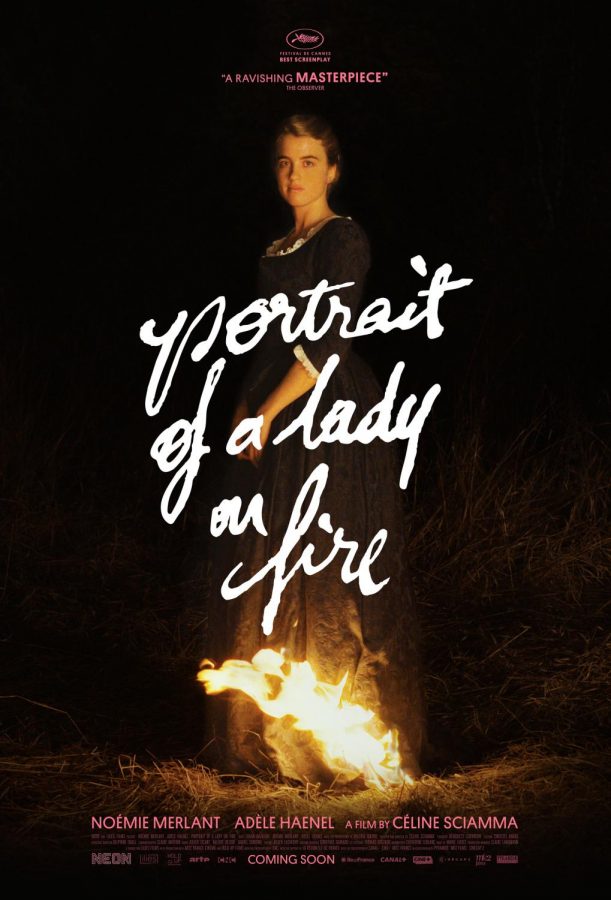

Review: “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” burns with feminine passion

February 17, 2020

“Portrait of a Lady on Fire” is a beautiful and understated masterpiece that stands on the shoulders of great queer cinema.

Set in France during the late 18th century, the French period drama follows professional artist Marianne, played by Noémie Merlant, as she is tasked with creating a portrait of the reclusive aristocrat Héloïse, played by Adèle Haenel, and having the painting sent to her subject’s future husband, a Milanese nobleman. However, it is not without some challenges as Héloïse herself proves to be a difficult subject, as she refuses to pose and even smile. Moreover, her sister, who was previously betrothed to the same man, had killed herself to avoid the marriage. As a result, Marianne tries her best to be her companion while secretly committing her physical features to memory.

As the two get to know each other better, what follows is a tale of forbidden love that is disarmingly enthralling. Sure, Marianne and Héloïse’s romance might be doomed when taken into context with the time period at which it’s based, but what’s interesting is that the film doesn’t deal in sentimentality when dealing with it. Writer and director Céline Sciamma paints a picture of feminine bliss unrestrained by the forces of society. The fact that it is mostly set on a remote island punctuates that utopian feeling, where the world outside, not yet introduced to women’s rights, can never condone the fact that women can be free to be whatever they want to be.

Sciamma visually treats the film with elegance with the help of luscious cinematography from Claire Mathon. Each of the frames are sensationally gorgeous with their use of candlelight and embers, evoking the likes of Stanley Kubrick’s “Barry Lyndon.” Music is used sparingly, but when its is featured, it effectively makes for powerful moments. The use of Vivaldi throughout the film is a great example, as well as an intricate, spine chilling acapella piece from women gathered on a bonfire during a local village festival.

The women in question sing a simple Latin phrase, “fugere non possum”, which translates as “we cannot escape”. This dual expression of fatalism and faith features prominently throughout the film. While Marianne and Héloïse cannot dodge their feelings for each other, they find themselves at the same time longing to stay in the remote island they are situated in, where they know they can live free of the restrictions imposed by a patriarchal society. This also plays into the film’s theme of equality. Young household maid Sophie, played by Luana Bajrami, is treated like a young sister by both Marianne and Héloïse, even accompanying her to an abortion.

With its relative absence of the male gaze, it can be tempting to describe “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” as a feminist tale. It certainly has such elements, as its female characters inhabit a utopian wonderland after all. But Sciamma refuses to reduce the film to such a description. Instead, it effectively shows that with isolation comes possibility, and even a measure of freedom. When Marianne first meets Héloïse, she becomes fearful when the latter breaks into a run towards a cliff. Héloïse responds as a matter of fact that she had dreamed of running along the fields. Suddenly, what appears to be fatalistic turns out to be exhilarating.

With “Portrait of a Lady on Fire”, Sciamma has a great command of structure. Most of the action is structured as a flashback, which is triggered at an art class where present-day Marianne teaches a group of young women how to craft portraits. Moreover, the theme of love and longing permeates the film, with overt and implied allusions to the legend of Orpheus and Eurydice as well as Marianne’s hidden grief over the end of her tryst with Héloïse. The film takes its time building up into a big emotional climax, cementing its status as a trendsetting fixture in the LGBTQ canon.