Classics Review: “Manila in the Claws of Light” is a timeless tale of working-class hell

April 7, 2020

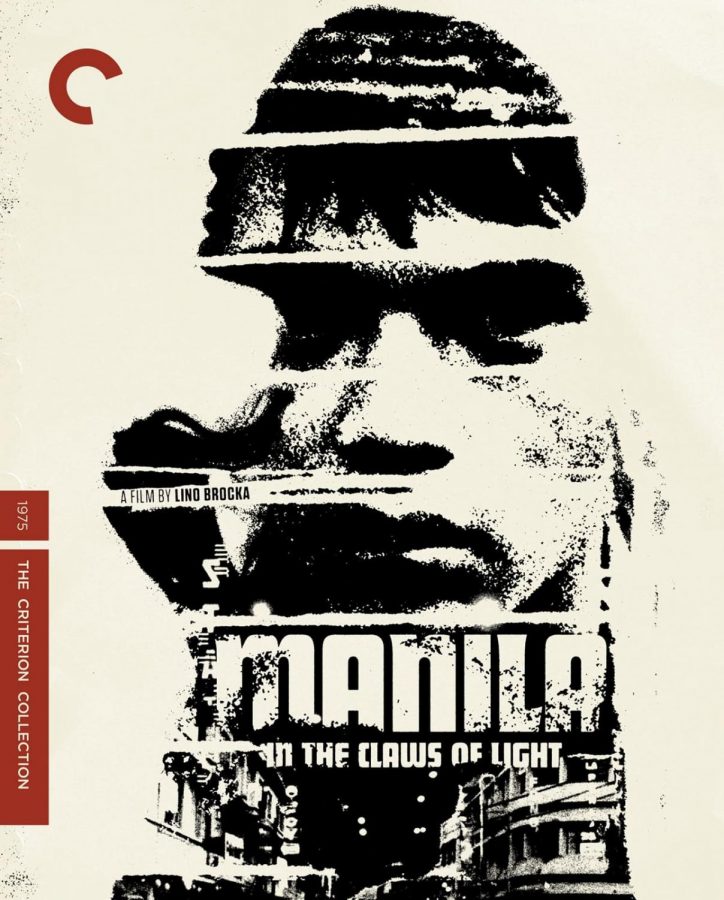

Lino Brocka’s seminal 1975 masterpiece “Manila in the Claws of Light” offers a realistic look on the titular city while also providing a universal story on life and death in the metropolis.

The film centers on Julio, played by Rafael “Bembol” Roco, Jr., a young fisherman from the country who ventures into Manila in search of his sweetheart Ligaya, played by Hilda Koronel. She had been lured into prostitution disguised as the promise of a better life and education in the city, and now Julio is determined to bring her out of Manila and the hellhole it represents. But first, Julio has to work through a grossly underpaid job as a construction worker if he has to financially make it in the city, and his brief travails into gay prostitution do not help matters.

Based on the novel of the same name from Edgardo Reyes, “Manila in the Claws of Light” owes its distinct brand of cinema verite to Italy’s postwar neorealist cinema of De Sica’s contemporaries. Cinematographer Mike de Leon, who also produced the film, emphasizes the hustle and bustle of the city, with several panoramic shots and deep focus compositions that do not bother to look away from the scrappiness of the streets as well as the people in it. A diversion from the concrete mess of Manila are the quick flashback scenes from the province where Julio and Ligaya used to live, evoking a sense of nostalgia with its diverse color palette that evokes the beauty of nature. Additionally, the tension of the city is also accompanied by the equally restless soundtrack of city chatter and melodramatic strains.

However, where De Sica ends “Bicycle Thieves” on a hopeful note, Brocka’s film does not. It plays like a scene out of “Dante’s Inferno,” only this time, the ever imposing metropolis that is Manila pays no heed to the struggles of its otherwise hopeful occupants and sends them to their fiery despair. Julio gradually finds himself disillusioned in his quest for Ligaya, and by the film’s final frames has his glimmer of hope erased by a newfound bitterness.

But it’s not always doom and gloom in Brocka’s world. In Julio’s construction gig, he finds solidarity in fellow workers who treat him as an equal and share their frustrations with their unfair boss, who pockets about a third of their salary every payday. One of them, Atong, takes Julio into his simple home in the cramped and dirty slums of the city. This sense of brotherhood comes out of the burdening weight of social inequality caused by capitalism, with Brocka providing a social commentary in the context of the Philippines being in a state of instability since President Ferdinand Marcos had declared martial law three years prior.

The indelible image of Julio standing by the signpost at the corner of Ongpin and Misericordia Streets, where he tracks down Ligaya to the Binondo district, is one of several symbols in a film rife with such symbolisms. Ongpin refers to Roman Ongpin, a longtime resistance fighter from Philippine history, while Misericordia means pity. Julio finds himself in this intersection of pity and revolt several times throughout the film, signifying his limbo on what to do when he eventually reconnects with Ligaya. Will he take pity on himself and his lover, or will he resort to rebellion to break free of the suffocating cycle that Manila represents?

“Manila in the Claws of Light” is not without risks, however. There have been whispers of Chinese racism in the film, from the unflattering depiction of the city’s Chinatown as a hotbed of prostitution to the character of Ah Tek, played by Tommy Yap, who has a role in Ligaya’s descent into the sex trade. Another point of contention is the subplot of Julio’s foray into gay prostitution, not in the novel but which Brocka added to Clodualdo del Mundo’s script. While deemed unnecessary by some, it can be argued that it is a clever and indispensable way to place Julio through the ordeal that his lover Ligaya had to go through in the same trade.

Owing to its title, the film explores the fatality of being drawn to the light. Julio searches for Ligaya, the “joy” and the light of his life, but finds himself ruined in the process. He ventures into the city, the light that supposedly brings financial stability, and faces disillusionment instead. The film’s last act hammers home this realization, making “Manila in the Claws of Light” Brocka’s magnum opus in Philippine cinema and cementing its reputation as one of the greatest films in the world.

To watch the film, click here.