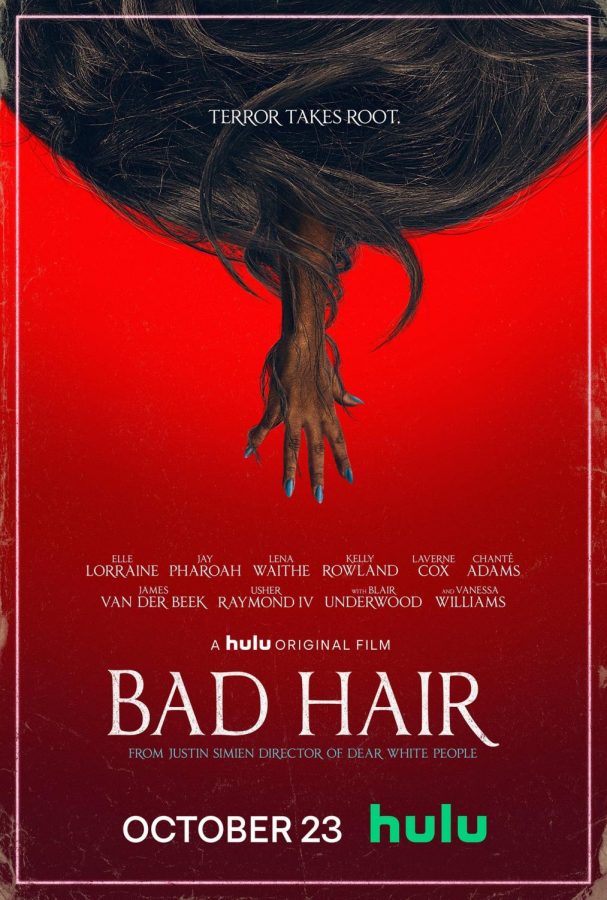

“Bad Hair” review: It’s not “just hair”

November 25, 2020

The delegitimization of Black women’s features, specifically their hair, has taken place throughout history. This is showcased in Hulu’s latest satirical horror film “Bad Hair.” Directed by “Dear White People” writer and director Justin Simien, it takes place in 1989, but many aspects of the film can be applied to society today.

The film’s main character Ana, played by Elle Lorraine, works for a music television station for years. However, her supposed progression through the ranks becomes stagnant. Ana desperately wants to become one of the hosts of the show, but her natural hair makes her a social pariah and according to her superiors, she did not have “the look” to have the spotlight.

The station later hires a new manager named Zora, played by Vanessa Williams. She introduces Ana to a new hairstyle: a sew-in which braids natural hair into cornrows and requires sewing in hair extensions. Ana’s life improves immensely once she gets this sew-in, as she gets the guy, the job and the respect. But at what cost?

Ana’s hair extensions turn out to be evil, possessed by the spirits of witches. She realizes these extensions have the ability to take over her whole body, leaving her powerless. She witnesses Zora and the rest of her counterparts get murdered by their own sew-ins. The extensions were later revealed to be shipped from a haunted plantation in Louisiana owned by Grant, played by James Van Der Beek, who owns the TV station that Ana works in.

“Bad Hair” does a great job of touching on westernization and how it negatively impacts people who are not white. Essentially, white people are to blame for a lot of racial issues, such as the delegitimization of a Black woman’s hair. The film stresses that the straighter your hair is, the more successful and accepted you will become. This can be seen interchangeably with the fact that the whiter you are, the more successful and accepted you will become.

This act of preferring straighter hair over tightly coiled hair is called texturism, which is an issue that Black women face on a regular basis. The fact that Ana was not chosen to be the host of the television station because of her natural hair is ironic because the purpose of the station was to promote and embrace Black culture.

The movie also touches on important issues such as sexism, fetishization, racial aggression, and cultural appropriation in the workplace. “Bad Hair” takes place in 1989, and yet it is scary how relatable a lot of these issues are 31 years later when we are supposed to be improving as a society. When I say improving, I mean making social spaces more comfortable for everyone who is not only cisgender, white and male.

I did not like how the movie implies that Black women only get sew-ins to elevate in social status or to look “better.” Many Black women get sew-ins to protect their hair or switch up their look, which is far from the reasoning of self-hate or wanting to be accepted. However, I do think that the hair extensions taking on a life of their own is a metaphor for self-hate and whitewashing. The reason why the extensions suck blood might be because of the way self-hate and whitewashing are emotionally and physically draining.

Simien’s brilliant balance of satire and horror for “Bad Hair” was a great choice. The jumpscares definitely went hard, but my fear subsided when I realized how low budget the film is. Still, this particular aspect adds to the comical feel of it all.

For me, the goal of this movie was to show how marginalized and oppressed Black women are in the workplace and in the world, with their hair being one of the main reasons. So saying things like “it’s just hair” is extremely ignorant because it is not “just hair.” Hair literally impacts how Black women are seen in society, and ultimately affects what life path they go down. “Bad Hair” also wants Black women to love their hair the way it is. Changing it always just ends badly.

To watch “Bad Hair” on Hulu, click here.