History complicates the Black community’s decision to get the COVID-19 vaccine

February 10, 2021

The COVID-19 vaccine has been introduced into the world, but many people of color, particularly Black Americans, are hesitant to get the vaccine due to distrust in the healthcare industry based on a history of exploitation.

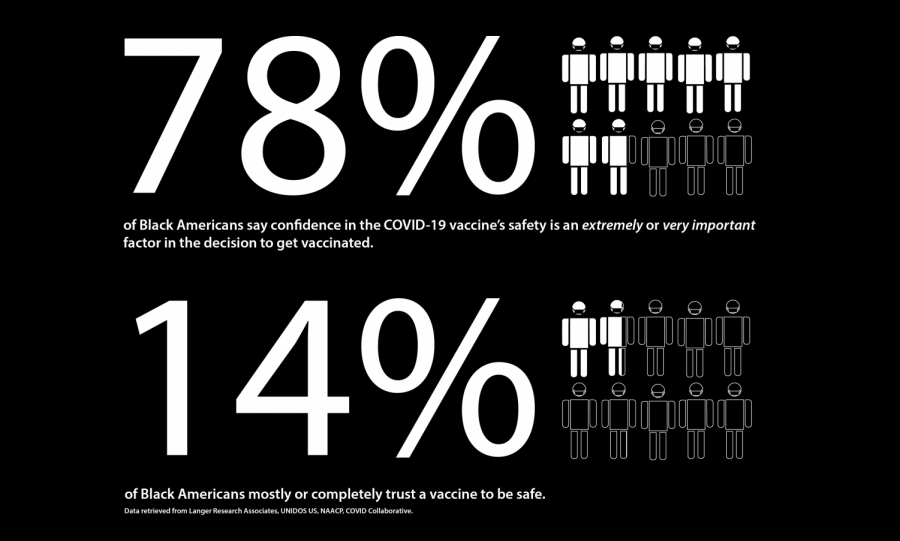

The NAACP, Langer Research Associates, and UNIDOS US conducted a research study in Fall 2020 about vaccine hesitancy in Black and Latinx Communities that revealed 78% of Black Americans surveyed feel confidence in the vaccine’s safety is extremely important in the decision to get vaccinated. However, the same study held that only 14% of Black Americans trust in vaccine safety.

The Coronavirus Vaccine Hesitancy study discovered that 55% of Black Americans know someone who has been diagnosed with COVID-19, and 48% know someone who has been hospitalized with or died from COVID-19.

Dr. Yvens G. Laborde, medical director of public health and global health education for Ochsner Health, said it’s important for the Black community to be included within the vaccine roll out as COVID-19 has disproportionately affected them.

“It is even more important that we ensure the Black community get equitable access to the vaccine. Getting the COVID-19 vaccination is one of the most important tools to ending this pandemic” said Dr. Laborde.

History is a major factor in the distrust between the Black community and the healthcare industry. According to the Coronavirus Vaccine Hesitancy study and Dr. Laborde, historical trauma from medicine within the Black community must be considered and treated as a valid concern.

Dr. Diana Grigsby-Toussaint, associate professor of behavioral and social sciences and epidemiology at Brown University School of Public Health, said that contemporary and historical evidence of unequal treatment for Black people in health care was laid bare by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Old wounds that had not properly healed in the first place have been reopened. For example, Ernest Hendon, the last survivor of the Tuskegee experiment died in 2004, less than 20 years ago – so the memory of Tuskegee is still fairly recent. With any relationship where there has been a betrayal, it takes a long time to rebuild trust. We can only hope that efforts will continue by members of the healthcare industry to institute policies to ensure health equity” said Dr. Grigsby-Toussaint.

In 1932, the Tuskegee Institute began the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” in Macon County, Alabama according to the CDC. Six hundred African American men, most of whom were sharecroppers, enrolled after being promised free medical care.

The study was conducted over 40 years although penicillin was discovered for syphilis treatment 15 years into the 1947 study. According to the CDC, researchers provided no care as the men died, went blind or insane to observe the severity of the disease.

While the Tuskegee Syphilis experiments were the most well-known example of the healthcare industry abusing the Black body without consent, this treatment happened decades before and after Tuskegee.

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks visited Johns Hopkins Hospital complaining of vaginal bleeding later discovering a cancerous tumor on her cervix. Dr. George Gey took a sample of the cells and was astonished when Lacks’ cancer cells doubled every 24 hours.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, Her “HeLa” cells were used without her knowledge to develop a cancer research method that is still used to this day. Her family struggled to get access to cancer health care even though their mother’s cells helped make it possible.

This history informs the choices Black Americans are making about getting the COVID-19 vaccine today.

Noel Jacquet, biology senior with a forensic science minor, had the opportunity to get vaccinated through her job, a toxicology lab at LSUHSC in Shreveport. As a Black student, she felt it was important to encourage others to get the COVID vaccine also.

Jaquet said she was skeptical about getting the vaccine but after researching the results of the clinical trials and how the vaccine worked, she was not hesitant.

“I researched the specific vaccine I was offered (Pfizer), side effects and if the reports of Bell’s palsy were true. I was happy with what I read and I had no hesitation after that. As a scientist I trust science” said Jacquet.

Bell’s palsy causes a temporary weakness of the muscles in the face according to Mayo Clinic.

Jacquet said she believes it will take many years for the Black community to regain faith in the American healthcare system.

“We have already began to educate people on the wrongdoings of this system and that is the first step. However, in today’s day and age, there are still health care professionals who believe that Black people do not experience pain the same as White people do. If these things are still happening today we still have a right to be skeptical of a system that has disproportionately disadvantaged us” said Jacquet.

Dr. Laborde said that it is his and his fellow physicians’ jobs to serve the diverse communities of the city, listen to their concerns and dispel myths about the COVID vaccines. Dr. Laborde stated that the myth that COVID-19 can be transmitted from getting the vaccine is false.

“While traditional vaccines, may use the virus itself, the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine uses a protein on the outside of the virus called the spike protein. This spike protein in the vaccine is not the COVID-19 virus. Therefore, you can not catch COVID-19 from the vaccine” said Dr. Laborde.

The spike protein stimulates your body’s immune system to produce a response as if it were a true infection Dr. Laborde explained. Dr. Laborde said that this built immunity minimizes your risk of re-infection if you encounter the same virus later.

Dr. Laborde told The Maroon that Ochsner health is making an effort to have open and honest conversations about vaccine safety and vaccine hesitancy.

Vaccinations within the Black community are not only complicated by distrust the vaccines’ effectiveness, but a lack of equity in vaccine distribution in the first place. Reports nationwide have shown racial disparities in vaccine distribution, with fewer doses going to predominantly Black neighborhoods in places such as Washington D.C. where Black neighborhoods experience higher COVID-19 death rates.

“We are leading community outreach programs where we provide people who have concerns about the vaccines an opportunity to express those concerns openly and honestly. One program at Ochsner, named the “COVID Conversation Series,” started early on in the pandemic to provide information on vaccine science and access, according to Dr. Laborde.

Jacquet said that she believes part of regaining trust will come from educating the current professionals on their unconscious bias.

The Black American community is two times more likely to trust a messenger of their own racial/ethnic group compared to a White counterpart according to the study.

Jacquet said people must be looking to educate themselves about the vaccine.

She also mentioned that the hesitation for Black people to get the vaccine not only comes from trauma and lack of information but the fear of what the long term effects will be.

“Because the vaccines are new, it is not yet known how long your immunity will last. It could be that the COVID-19 vaccine is eventually a seasonal one, like the flu shot. More research needs to be done to confidently say how long it will last and those studies are ongoing” Dr. Laborde said.

Laborde said the two vaccines currently being distributed now are safe and effective. The CDC and the FDA have an extensive vaccine safety monitoring and surveillance system that monitors for any adverse events or long term effects said Dr. Laborde.

“The most common side effects reported are headache, fatigue, muscle pain, joint pain and a mild fever. Nearly all resolve within 24 hours” Dr. Laborde said.