Letter: Appropriation has a real cost

March 15, 2021

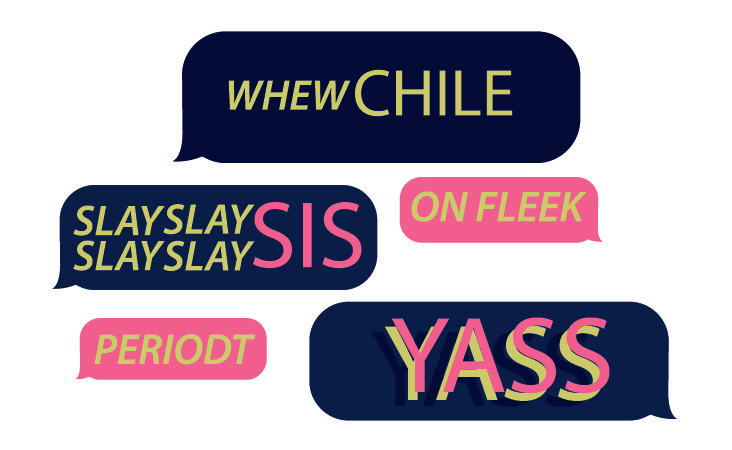

Khayla Gaston’s article on African-American English highlights one aspect of the broad issue of cultural appropriation and racial stereotyping. While African-American English is ostracized in the workplace or academia, it is seen as the blueprint for popular culture. Phrases like “whew, chile” or “spill the tea” originated in the Black community but have crossed racial lines via social media. But what happens when Black culture gets commodified and used as a marketing tactic? What becomes of the Black people who popularize phrases or generate viral memes.

As we saw in 2016 with the popularization of the phrase “bye, Felisha” non-Black people will adopt a phrase seen on the internet and use it without context or understanding, even earning money from it while the Black creators get nothing. I’ve personally seen white women use this saying as a friendly goodbye, pretty discongruent with its origin as a rude dismissal of a drug addicted perpetual mooch in the Black classic film Friday. This phrase got repopularized to the point where companies included it in their marketing strategies, water bottles and tote bags have the phrase on it, all with the name “Felisha” misspelled as “Felicia.” There’s even Bye, Felicia! the card game, which has nothing to do with Felisha or Friday. Despite this phrase being yanked from the 1995 flick, do any royalties go back to the Black producer, Patricia Charbonnet?

An even bigger example of this appropriation is Kayla Lewis and her coining of the word “fleek” or “on fleek.” What started as a Vine video of a 16-year-old praising her eyebrows for being cute ended up as one of the most popular sayings of 2014. Once again, companies were tweeting that their products were “on fleek” and merchandise was sold with this phrase, yet Lewis never received a dime. Even worse in this instance is the word had no specific meaning until Lewis proclaimed her eyebrows as on fleek, she brought the word meaning and it was taken from her.

However I am optimistic that the commercialization of appropriation will end and Baton Rouge car salesman Durell Smylie gave me that glimmer of hope. Smylie went viral on Instagram and TikTok for his catchphrase “where the money reside,” dancing and bubbly personality. Smylie was able to trademark his phrase and announced he pursued legal action against a white car salesman who attempted to remake the viral video. The white salesman donned a fake blaccent, proving that it wasn’t just the phrase he was commandeering, but Durell Smylie’s natural existence as a Black man. Smylie protected his creation and refused to let his personal brand become a trend for others to make money off of without crediting him.

Kanye West said it best in his song “Crack Music:” “this dark diction has become America’s addiction, those who ain’t even black use it.” We continue to fight to have African-American English widely embraced as a valid linguistic form created by and for Black people, not just as a trendy marketing strategy. Let our first step toward this goal be paying and crediting Black content creators for sharing their humor and joy with us.