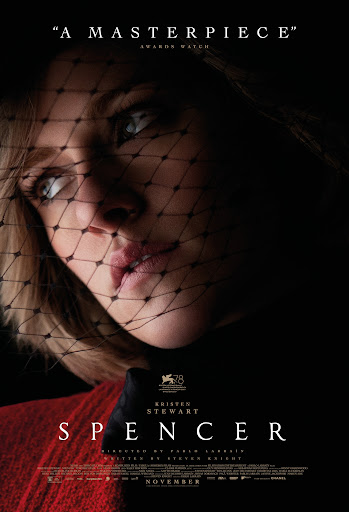

“Spencer” review: How ambiguity allows for truth

Courtesy of Neon

“A fable from a true tragedy,” reads an inscription at the beginning of Pablo Larraín’s “Spencer.” The line between real and imagined is blurred in the fictionalized biopic. It is hard to separate Diana, the person, from Diana, the princess, as her reign has permeated popular culture for years. Chronicled and consumed, her life has been romanticized and exploited through different mediums over the years.

Larraín doesn’t claim to tell the entire truth in his new film, but rather he creates an imagined reality grounded in royal tradition. His absurdist adaptation of a three-day holiday in the countryside of England relies on ambiguity to chronicle the controlled chaos of the royal family and a truth of a woman being silenced.

In our first moments with Diana (Kristen Stewart), she becomes lost in a place once familiar to her, Norfolk, where she grew up. Park House is close to Sandringham, where the royal family celebrates Christmas. Having driven herself without permission, to grip at any remaining sense of herself, she gets lost in the most formidable familiar place for a person: home. Or near it.

“Where am I?” she asks a cashier at a local cafe. Disoriented from her consuming role and driving the roads of her youth aimlessly, she is distant from who she once was, her “true” self, while being in such close proximity to her childhood home. Late to the manor, Diana pushes at time constraints and tradition for the remainder of the film.

Set in a controlled environment, the holiday is regimented while our protagonist is reaching for any sense of agency or control of herself. Once arriving at the gated grandeur of Sandringham, Diana crosses a moat, separating the property from the public and separating the royals from reality. Upon entering the palace, Diana is immediately required to be weighed on an antique by the queen’s watchful eye and Sandringham’s Major (Timothy Spall). This tradition was started during the reign of Edward VII, who required guests to gain three pounds to ensure that they ate and enjoyed themselves. Enjoyment cannot be measured. It cannot be controlled. However, tradition does not take that into consideration.

Consideration is absent in the holiday at Sandringham. Rather than be concerned with Diana’s loss of time and self, the power of her image is more important to the crown. Prince Charles (Jack Farthing) lacks empathy in regard to his wife. Diana, knowing that her husband is having an affair with Camilla Parker Bowles and breaking down from the impossible nature of her role, is attacked by Charles for acting on her own and not within the unit. By arriving late to dinner, it is the only agency she has left. “You have to be able to make your body do things you hate, for the good of the country,” Charles tells her. His oversimplified assertion is acidic to Diana, as she becomes beaten down by separation of herself and her duty and role to her country. She cannot bring herself or her body to continue on.

Diana’s body is the one thing that she has control over, as she inflicts pain to it: inducing vomiting before dinner, which represents her real battle with bulimia. After Charles gives her the same pearl necklace he gave to Camilla, his mistress, Diana rips it off of her at the dinner table, as if to be released from the constraints she is bound by. The pearls scatter into her soup, and she eats it. After consuming the constraints, she leaves the table to vomit it up. It doesn’t belong to her or in her. She does not belong there. She knows this, and she is constantly reminded of it.

In this attempt for respite, she is unable to grapple with the grief of her old life she has lost. Someone alerts her it is time for dessert, and her attendance is required. She is at war with her body and herself, resorting to self harm as self control. Her body’s movement represents her defiance in the monotonous system. Stacked against her, she rejects the restrictions of time by pushing away from planned gatherings, dragging her body down the decadent halls.

“There has to be two of you,” Charles insists: one for “the people” and one in private. The juggling of a facade and real life is blurred. She is no longer in a space to recognize fact from fiction. Often, our public image is shaped by our actions. But for Diana, her actions are scripted. Her perception permeates her personal life. There is no longer a line drawn between real and imagined. The severity of the loss of sanity is felt throughout the film, as the facade festers with the audience, unable to shake the chains she is kept in for hours after leaving the theater.

In the kitchen hangs a sign above the staff: “Keep noise to a minimum. They can hear you.” While the royals are representative of “they,” it does not appear that they hear anything. Or, they choose not to hear anything. As Diana stumbles and screams for help out of fear of losing herself, the culture of silence and suppression does not allow for her sound to be significant to those in power. Lack of listening and lack of consideration leaves little room for sanity.

Rather, a Christmas tradition becomes a place of captivity for Diana, as she is haunted by the ghost of Anne Boleyn, someone who will listen because she has been in the same position of powerlessness. As their fate is intertwined, with husbands that chose someone else, and sacrifice their wives to the wolves, the past plagues Diana. “Here, in this house, there is no future. Past and present are the same thing,” Diana admits to her boys William and Harry, who are her closest companions.

Defiant to tradition, Diana pushes boundaries and blurs lines to assert control for self-preservation. Mimicking Diana’s spirit, Steven Knight’s screenplay is absent of tradition, throwing the preconceived notion of a biopic’s structure away. Absurdism becomes the best way to depict a damaged damsel in a broken system that benefits no one.

Time is told through Diana’s pre-determined rituals of the day. First, she takes the assigned attire for the day off the rack. Each is labeled for each event she has, tagged “P.O.W” for “Princess of Wales” or more accurately “Prisoner of War.” Once she has her dress that was predetermined, time can be understood with the anticipation of sitting down to dinner once she violently vomits.

While Diana faces persecution through perception, her moments with her children show the resilient remarkable nature of motherhood. She lives with intention in her interactions with them, rather than being thrown around by the royal family like a rag doll. She sees safety in their presence, while actively trying to protect them from the pain she is enduring. It is hard not to look at these scenes through a devastating lens, as Harry is hopeful and silly with his mother and as William seeks answers and advice from her, knowing that these boys will soon lose the most authentic connection in their predetermined destiny. Legacy is out of one’s hands once they pass, but Larraín gives sound to the suppression and strength of Diana’s voice in “Spencer.”

Stewart’s performance matches the ambiguous nature of the biopic. While she does not mysteriously melt into an exact replica of Diana, her humanity and hushed nature is familiar. As we follow this woman through persecution, we empathize with her powerlessness, hoping for her peace and liberation. Hoping that her truth will be told and held onto.

“Spencer” is now available on demand.

Ella Cheramie is a junior from New Orleans studying English Writing with a double minor in Social Media Communications and Theatre at Loyola University...

chloe • Dec 6, 2021 at 5:48 pm

good read