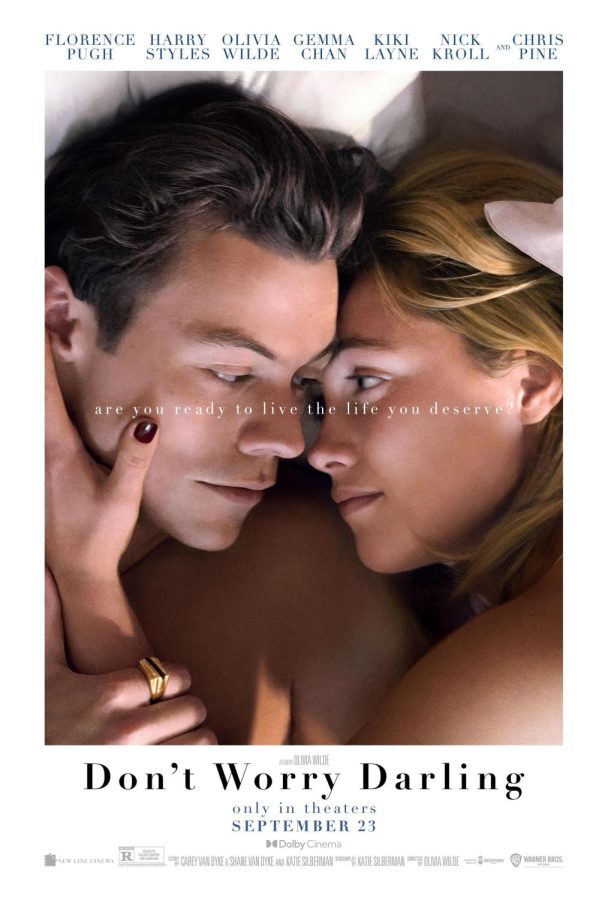

“Don’t Worry, Darling” review: Wilde’s movie surrounded by political culture, news falls flat

October 5, 2022

Editor’s Note: The following review contains spoilers for “Don’t Worry, Darling.”

All publicity is good publicity, but in the case of the never ending “Don’t Worry Darling” saga, no public relations team can save Olivia Wilde’s vapid dollhouse from burning down. After a messy press junket in Venice that gave the world an insatiable amount of water-cooler banter, anything on-screen falls flat of the off-screen lore. Alleged feuds between Wilde and Florence Pugh have set us up for conversations surrounding women in film, how we talk about them and how we treat them. Romantic affairs on set between Harry Styles and director Olivia Wilde have opened up discussion on ethical workplaces and how gender dynamics play into them. “Spitgate,” or Harry Styles looking like he spit on Chris Pine, has allowed for some humor amidst deep discomfort. It provides stimulating conversation. But, what about the film itself?

And the truth is that it has become impossible for the public to separate the piece from its pop culture wreckage.

But, like the film sets up, nothing that we have been told is true. This is clear with the flaws in the messaging of the film. What was promised to be a celebration of female pleasure turns out to be one of female control and non consensual servitude. What was supposed to be a female thriller falls flat, giving the audience no thrill at all – rather, maybe an accidental laugh or two. And, while Wilde’s saving grace in press was to encourage us to judge the film by its own merits rather than real world gossip, the film itself is even more disappointing filled with false promises and surface level feminism.

“Don’t Worry Darling” opens with a party at the Chambers’ home: a perfect mid-century haven, with zero-subetely and a top 40 hits soundtrack that lets the viewers know: it’s 1950, we swear! We follow Alice Chambers (Florence Pugh) as she slowly unravels learning that her life is a lie.

Her husband, Jack (Harry Styles), is the reason that their candy-colored cul-de-sac life is so “perfect.” Working for the ubiquitous “Victory Project” along with their neighbors, he and the men of the subdivision drive off to the vast desert to work on “progressive materials.” Their boss and leader is Frank, a man with stature and charisma, someone you listen to when they talk, phones into the radio each day for motivational sermons that the women of Victory listen to, as they vacuum the house, cook for their husbands, and await their return with a cocktail in hand. It appears under gender roles and routine, there is happiness and order.

That is, until Alice starts to see plot holes in the story of her own life. Overt perfection of the dystopian desert society is obnoxiously driven into the viewers: lipstick, tea-length dresses, frilly aprons– womanhood in Victory is traditional and submissive. When we first see the wives without their husbands, it is in a dance class taught by Shelley (Gemma Chan), who is Frank’s wife. Almost as intimidating as her husband, Shelley leaves no room for interpretation or self-expression.

“There is beauty in control. There is grace in symmetry. We move as one,” the wives chant in unison. In celebration of an era of conformity, the film tries to play with the power dynamics of marriage, the suppression of identity within femininity, the fragility of men, and the fine line between female pleasure and female control.

But like the choices of production design and the screenplay itself, it lacks subtlety and leaves no faith for viewers as it explicitly spells out what is happening for the majority of the film. While everything is not supposed to be what it seems, it is.

Victory is so idyllic through incredible production design by Katie Byron, John Powell’s anxiety-inducing score, and Arianne Phillips’ triumphant costuming. But, the fishbowl is set up to fail, through storytelling decisions that push us further and further into nothingness.

Perhaps suspense in the film is suppressed because of the press leading up to the film, where Wilde incessantly gave major plot points away comparing Chris Pine’s character to Jordan Peterson, overcompensating through explaining the world of white men on the internet and their rage, or blatantly saying the film mimics The Truman Show, a film where everything is not what it seems. Perhaps the film also lacks suspense because of the overpromising of what the film was going to be versus what it was.

What was promised to be a film about female pleasure grossly turns to a film of nonconsensual pleasure and female control. What it tries so painfully to achieve it does a disservice to. The plot twist about half way through the film (spoilers ahead) reveals that Alice is in Victory without a choice. Her former boyfriend Jack is not the suave Mad Men-esque British Jack Chambers we know. Rather, he is an incel who was jealous of his girlfriend’s success in the real world. Before being a subservient housewife, Alice is an accomplished surgeon. And Jack, well, Jack spends his time unemployed listening to male propaganda and playing on Discord.

In the discovery of Alice’s lack of agency, everything ultimately feels sickening behind the intention of the film. Did Wilde understand this had nothing to do with female pleasure and everything to do with male domination amidst feeling threatened? Why was the messaging so “Me,too”-esque for a film that presents gender norms and tropes of warped reality that we have seen time and time again, giving us no new perspectives to ponder?

While the film works at something ominous happening among Victory, it never gets off its feet. Falling apart from already loose ends, the third act is the final nail in the coffin. Without a final spoiler, the ending creates more confusion without ever giving proper context or answers to major parts of the film.

Margaret, Kiki Loyd’s character, is never given a resolution, nor enough screen time considering she is the whistleblower among the group. The red planes that crashed from the air are never explained. The constant routine earthquakes are never mentioned again. Jack and Alice’s life before is still fuzzy to the viewers, and a missed opportunity is illuminated. What were Jack’s motivations for putting Alice and him in this simulation? Perhaps Styles’ acting was not ready to push the complexity of male manipulation fully forward. Perhaps the off-screen lore was accurate and much of the original film was cut. Regardless, like the characters in their cherry red shiny cars, it drives itself in circles, with no sense of a destination or purpose.

Amidst the lack of direction, Florence Pugh breaks down the walls of Wilde’s paper doll house effortlessly. Navigating each plot hole, each turn in the structurally unsound rollercoaster of a script, you cling to her as a viewer. You fear for her. You empathize with her, and you want so bad to take her out of this place. She excels by taking the reins of the getaway car, and flies past each of her co-stars in creating depth and layers that are unspoken. Pugh works at turning a flat character into a fiery woman, desperate for answers and not backing down no matter her fear.

It’s fascinating that the movie itself has become deeply meta. Just as Frank is selling the Victory Project with false messaging and warped intentions, so too was Wilde in anticipation of the film.

“Don’t Worry, Darling” is now available in theaters.