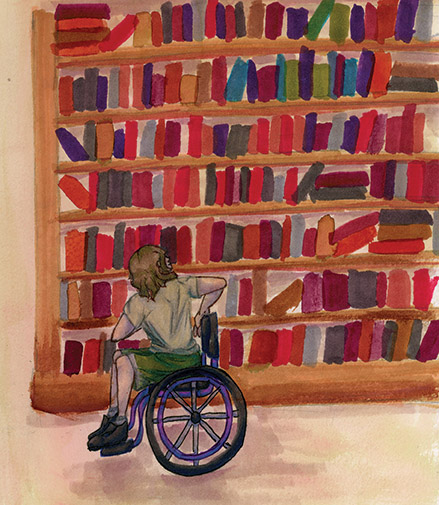

OPINION: Loyola needs to increase campus accessibility

February 12, 2023

The trip in a wheelchair from Buddig Hall to the inside of Mercy Hall is roughly 20 minutes. I have to navigate through the crowded parking lot, and the patterns on the ground that cause a kind of resistance on my wheels that require a full body effort. I attempt to enter on the side closest to me. I can’t get in. I’m faced with a set of stairs. This is okay, I will attempt to find another entrance. Wheeling to the other side of the building, facing Calhoun, I find the sidewalk shrinking around me. At this point, I’m already five minutes late to class. The sidewalk isn’t big enough to fit my wheelchair, and the broken, uneven pavement makes my wheelchair harder to control. I start panicking. There is no way I can make it to class on time at this point, and I’ve found myself unable to control my wheelchair. I’m going down this short slope and my wheel has fallen off of the sidewalk. I know what will happen next. It’s 9:23 a.m. on a Tuesday morning, and I’m sitting in the mud several feet away from my wheelchair. I sit in this position for a minute. I feel like this feeling will last forever. Why should I use my wheelchair? If this is supposed to help me, then why do I feel like I often find myself in these trapped positions of embarrassment and anger? I need my wheelchair. I find my circular thoughts are disrupted by students.

“Oh my god I think she fell out of her wheelchair! Oh my god! We have to help her.”

In my shame and embarrassment, I find myself becoming a public spectacle. No one speaks to me. They begin touching me, grabbing me, pulling me out of the mud.

“No, it’s okay, I’ve got it. I can get up.”

I bet after this they will carry their head up for the rest of the day knowing that they are saviors. I mean, without them, what would I have done? They’ve misgendered me, broken my personal space, and dehumanized me.

“You poor baby! I hope you’re okay!”

At this moment, I am nothing more than my wheelchair. As an ambulatory wheelchair user, not only do I feel unsafe using mobility aids on campus, I feel like it defines me negatively.

The ADA defines a person with a disability as a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. This includes people who have a record of such an impairment, even if they do not currently have a disability. It also includes individuals who do not have a disability, but are regarded as having a disability.

According to Chris Rice, head of residential life, all buildings of Loyola’s campus are ADA approved. Yet, the truth is that our campus is far from that. The ramps are too steep, the ADA push plates don’t work, elevators break down often, and students on campus don’t know how to behave themselves. When elevators break down, it’s an issue for almost everyone, yet it affects students with disabilities more so. No one receives any notice about a broken elevator. While most students can quickly decide to trek down the stairs instead of being late to class, those of us with disabilities cannot. TRIO is a themed living community on campus that accepts students by the following: they are identified as a first-generation college student, have a disability, and/or come from a low socio-economic background. For a TLC that has one of the main aims is to assist students with disabilities, why are these students placed on the 10th floor of Buddig? How is this fostering an accessible environment?

In the past, discussions of accessibility on campus have been spoken for by able-bodied people. Due to this, one thing never discussed is the campus culture around using mobility aids on campus. While this holds true in most public spaces, at Loyola, it fills me with fear. Using my wheelchair on campus has made me a direct target for death stares, unwanted touching and attention, and comments that leave me feeling insecure and isolated. Elevator rides are longer than ever. I get prodded with questions. “Why are you in a wheelchair?” “What’s wrong with you?” “Are you like sick or something?” These are the questions you might expect from a child. Not so much a group of 18-to-19-year-old college students.

In the future, I would like students on this campus to be able to feel as though we are safe. Safe to express ourselves, safe to use our mobility aids, safe to walk with a limp, and be okay with just that. Being disabled is not a hard label or definition, we as a campus community need to understand that disabilities span far and wide across our campus, and what is and isn’t a disability isn’t something for an able-bodied person to define. Able-bodied students should have a more nuanced understanding of the disabled identity and the truth of their privileges when simply walking around campus. Look around your dorm, your classrooms and ask yourself: is this fostering a space for students with disabilities? Are you complicit in these issues? Where do you stand?