Professors uncertain about new contracts

March 22, 2023

Loyola is releasing contracts to faculty in a few months, and some professors are skeptical that promises of increased wages will be kept by the university.

Last summer, Loyola interim president Rev. Justin Daffron S.J. gave a speech where he provided what he hoped to be a short-term solution to Loyola’s low faculty salary rate. He also said he hoped to have a more permanent solution to increase the low salaries in 2023.

The Maroon reported in September of last year that Loyola faculty wages were 25% lower than the national average, around the same time Daffron said Loyola issued $1.4 million in one-time payments to 212 employees identified as receiving compensation below the target range for their position. These one-time payments were kept confidential, and Mark Yakich, an English professor, said there has been no recent communication between administration and faculty over wages.

The current lack of growth in wages is concurrent with higher student enrollment and an increased number of faculty members, according to English professor and Director of the Center for Editing and Publishing Christopher Schaberg.

Schaberg said pay is lower than it was made out to be. He said that the 25% figure is a percentile, meaning that 75% of Loyola’s professor’s peers make more than them.

Yakich said instead of a consistent salary, faculty received a one-time compensation package last fall to increase Loyola’s percentage behind other universities’ faculty pay. Compared to similarly-sized universities, Yakich believes that Loyola is further behind than the statistics lead on.

Yakich and other faculty members are now waiting to see if the upcoming contract will again include a one-time payment or not.

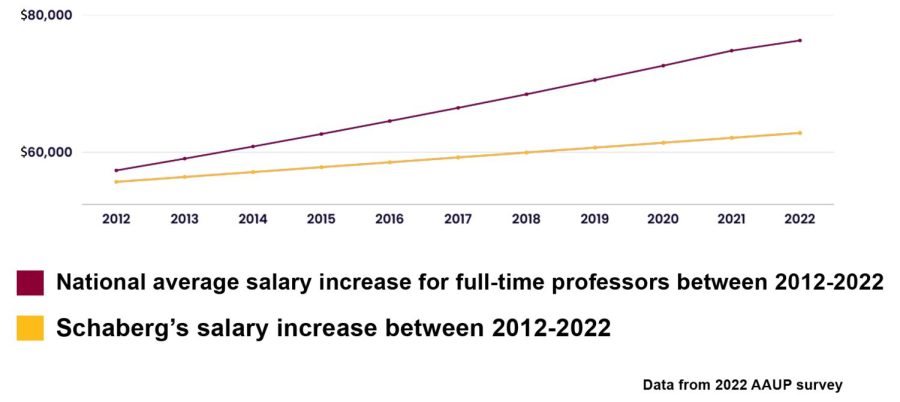

Schaberg expressed gratitude for his one-time payment, but he said it showed him and his colleagues just how little they feel they are regularly paid. When the new contracts roll out, there will be 30 days to sign, and faculty will see whether or not the salary is fixed. When he began working at Loyola, Schaberg’s pay was $53,500 and has gone up $10,000 over his fourteen years – even after promotions to associate and later full professorship. This is particularly worrying considering that the cost of living has also crept up, Schaberg said.

Schaberg said he has seen the impact of the lower wages, noting that the English department has lost ten tenured professors over the last ten years. These tenured positions and vacancies are disproportionately replaced with adjunct professors and other instructors on one-year contracts, putting pressure on their job security. Schaberg said that this issue has made his colleagues feel either defeated or angry.

“A lot of faculty are so beaten down, and they’re just resigned,” he said.

Yakich and Schaberg both said that, in its current state, Daffron’s plan is more of an abstract and uncertain mission. Schaberg hopes it will come to fruition with a higher and fixed salary in the new contracts, but he doesn’t believe it will.

Schaberg believes this one-time payment may happen next year but not this year, and that the salary on this contract will return to the old low salaries.

“I think that’s what’s going to be so disappointing,” Schaberg said. “Because they’ve told us how much they know we’re worth, and we’re worried we’re going to get contracts saying ‘we’re still going to only pay you this much.’”

Schaberg said that if this happens it may ultimately lead professors to look elsewhere for work.

“It’s made me look seriously for other jobs,” Schaberg said. “Which is hard because I actually love it here, I’ve been here for fourteen years, I love my students.”

However, Schaberg said he’s at a point in his career where he needs to be recognized for his efforts.

Schaberg said he believes Loyola has the money to spend on faculty, and more money should be allocated to professors as it directly impacts students as well.

Because Daffron is in a precarious position as interim president, Schaberg said that he doesn’t have the usual authority for situations like this.

“We need leadership to say ‘we need to do the right thing,’” Schaberg said.

University spokeswoman Patricia Murret did not return multiple emails and voicemails requesting comment for this story.