ST. LOUIS – American nuns described as dissenters in a Vatican report that ordered an overhaul of their group said they will talk with church leaders about potential changes but will not compromise on the sisters’ mission.

Sister Pat Farrell, president of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, called the Vatican assessment of the organization a “misrepresentation.” But she said the more than 900 women who attended the group’s national assembly this week decided they would for now stay open to discussion with three bishops the Vatican appointed to oversee them.

“The officers will proceed with these discussions as long as possible but will reconsider if LCWR is forced to compromise the integrity of its mission,” Farrell said at a news conference, where she declined to discuss specifics.

The organization represents about 80 percent of the 57,000 Roman Catholic nuns in the U.S.

The St. Louis meeting was the group’s first national gathering since a Vatican review concluded the sisters had “serious doctrinal problems” and promoted “certain radical feminist themes” that undermine Catholic teaching on all-male priesthood, birth control and homosexuality. The nuns also were criticized for remaining nearly silent in the fight against abortion.

Farrell acknowledged the nuns’ plan going forward was vague but noted the process would stretch over five years and had only just started. The board is expected to meet with Seattle Archbishop Peter Sartain, who will be in charge of the overhaul.

“Dialogue on doctrine is not going to be our starting point,” Farrell said. “Our starting point will be about our own life and about our understanding of religious life, and the (Vatican) documents, in our view, misrepresentation of that, and we’ll see how it unfolds from there.”

The Vatican orthodoxy watchdog, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, undertook the assessment in 2008, following years of complaints from theological conservatives that the American nuns’ group had become secular and political while abandoning traditional faith.

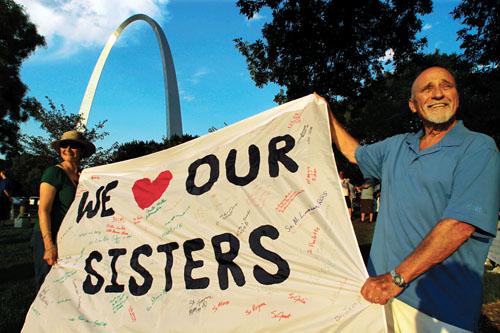

The critique, issued in April, prompted a nationwide outpouring of support for the sisters, including parish vigils, protests outside the Vatican embassy in Washington and a congressional resolution commending the sisters for their service to the country.

After the Second Vatican Council of the 1960s, many religious sisters shed their habits and traditional roles as they sought to more fully engage the modern world. The nuns said prayer and Christ remained central to their work as they focused increasingly on Catholic social justice teaching, such as fighting poverty and advocating for civil rights.

“I think what we want is to finally, at some end stage of the process, to be recognized and understood as equal in the church, that our form of religious life can be respected and affirmed,” Farrell said.

She said she wanted to create church environment that allows them to “openly and honestly search for truth together, to talk about issues that are very complicated” and “that there is not that climate right now.”

The Vatican review occurred at a time when the future of women’s religious orders in the United States already was in question. The number of sisters has dwindled from about 180,000 in 1965 to 57,000 now, according to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University. The average age of the sisters who remain is around the 70s. While some orders are recruiting new candidates, many still are struggling to keep them.

The Vatican has separately conducted an Apostolic Visitation, or investigation, of all the U.S. women’s religious orders, looking at quality of life, response to dissent and “the soundness of

doctrine held and taught” by the women. The results of that inquiry have not been released.

Cardinal William Levada, who until recently was the head of the office that conducted the Vatican assessment, had told The National Catholic Reporter that if church leaders cannot reach some agreement with the sisters’ group, the Vatican could withdraw official recognition.

In 1992, the Vatican already had created a separate U.S. group for sisters with a traditional approach to religious life. The Conference of Major Superiors of Women Religious represents

about 20 percent of American nuns.

Still, Farrell gave no sign that her group would back down.

In a speech, she said the sisters have been asking themselves whether the Vatican assessment was an “expression of concern or an attempt to control?” Farrell ended the address with a phrase she learned while serving the church in Chile when the country was under a military dictatorship.

“They can crush a few flowers, but they can’t hold back the springtime,” she said, before receiving a standing ovation.