Financial equilibrium project expected to increase enrollment

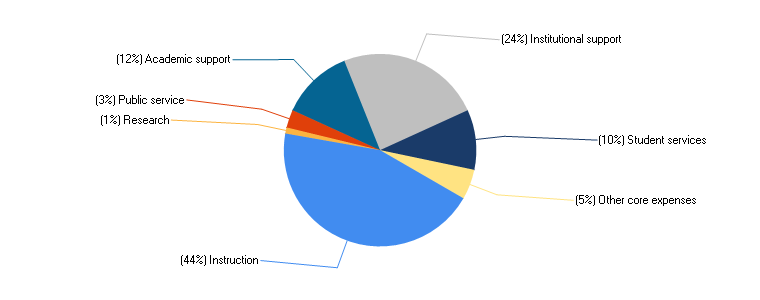

In 2014, 44 percent of Loyola’s expenses went towards compensation for instruction, the majority in the university’s expense breakdown, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics Photo credit: IPEDS Data Center

December 12, 2016

Loyola, a campus that thousands utilize daily, has a book value of almost $250 million dollars.

That would buy 67,661 tickets to Super Bowl 51 in Houston.

However, that amount is not even half of the university’s assets, which, as of 2014, totaled nearly $606 million. That’s enough for every current Loyola student to purchase 19 C-Store milkshakes everyday for the next four years.

There’s a lot to learn from Loyola’s 2015 Form 990, the school’s most recent available tax return. For example, Sodexo, the food service responsible for feeding the Loyola community, was compensated almost $6.68 million in 2014.

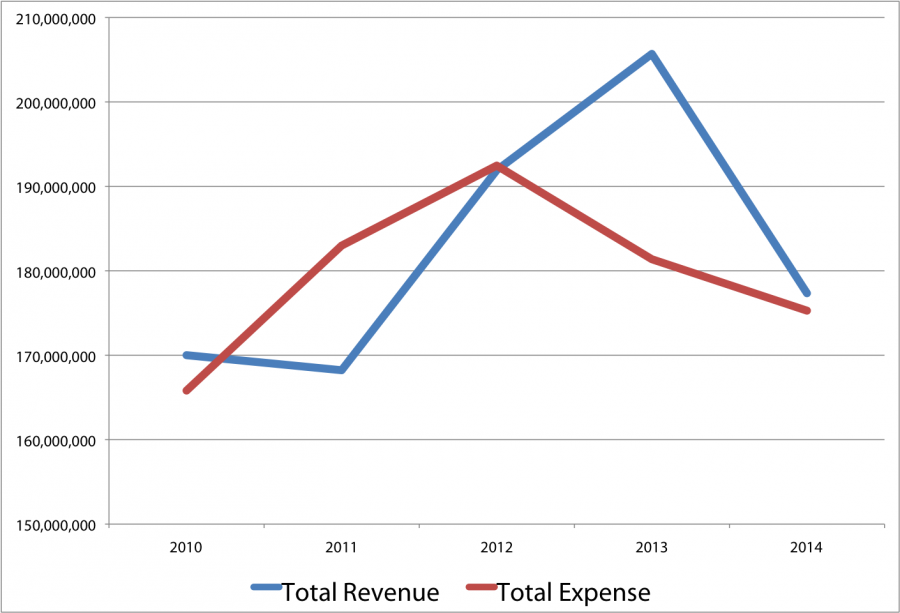

Loyola University New Orleans is an income-tax exempt corporation, worth over half a billion dollars in assets and responsible for the educations of over 4,200 undergraduate and graduate students. The school generated more than $200 million in revenue and over $180 million in expenses in 2014 alone.

All private universities and many public universities are exempt from taxes on any revenue related to their educational purpose, qualifying Loyola as a public charity in the federal tax code, according to the Association of American Universities.

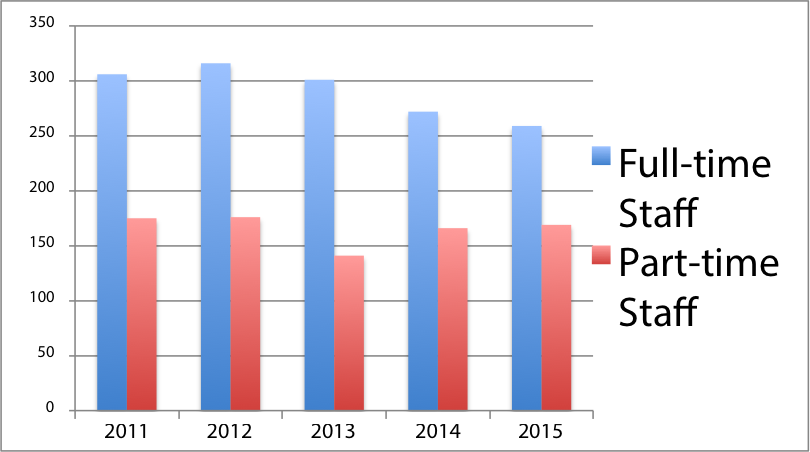

For an institution of Loyola’s scale to function, the school employs over 2,600 faculty, 259 of which are full-time instructional staff spread across the university’s five colleges: the Colleges of Business, Arts and Sciences, Music and Fine Arts, Graduate and Professional Studies and Law. There are also 169 part-time instructors as of 2015, according to Loyola’s Office of Institutional Research.

The difference between full-time and part-time instruction is what Howard Bunsis, chairman of the collective Bargaining for the American Association of University Professors, said is one of the largest, most common issues in universities nationwide.

“If you dig down to the detail, you see an incredible slow down in hiring full time faculty. It’s a huge difference. Students are being taught more and more by part-time faculty,” Bunsis said. “In every state, it’s the same story. It’s why I present to professors across the country.”

At Loyola, recent budget shortfalls have lead to a year-by-year decrease in total instructional staff numbers.

This decline of nearly 600 total staff, from 3,223 in 2012 to 2,633 in 2014, correlates with a decline in overall revenue, which primarily comes from the private school’s tuition and fees.

“Not a single private university has enrollment as under 50 percent of their revenue,” Bunsis said. “From there, the question is ‘how is that money being spent?’”

According to Leon Mathes, Loyola’s vice president of finance, the money from students’ tuition and fees drive the school’s revenue, making the university a “tuition and fee dependent entity.” He said at the end of the previous fiscal year, which ended July 31, 2016, tuition and fees accounted for 83 percent of operating revenues.

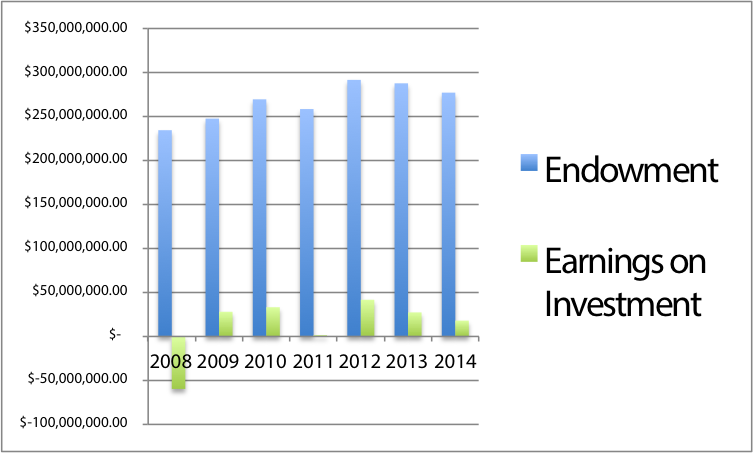

Mathes also said the school’s endowment, an investment fund comprised of over 400 individual funds, is strong.

“At July 31, 2016, Loyola’s endowment had a market value of $251 million. The endowment provides operating funds and restricted funds for such activities as scholarships, professorships and chairs,” Mathes said.

According to Bunsis, however, the return on operating investments varies per year, and typically only amounts to five percent of the total endowment.

Therefore, with over 80 percent of operating revenue coming from tuition and fees, enrollment numbers are the key. When enrollment estimates miss their mark, they cause the biggest financial issues for private universities — budgetary gaps that can take years to balance.

In 2012, Loyola had a freshmen class of 866 students, one of the largest classes in the school’s history. The following year, however, enrollment expectations missed the mark by 200 students.

To combat the budget gap following 2013’s enrollment shortfall, Loyola created the Financial Equilibrium Project, a multi-part plan that aims to reduce the university’s spending by $11.5 million by 2020.

The Rev. Kevin Wildes, university president, announced the plan last fall, following months of input from a special presidential advisory board, multiple financial committees and personal faculty discussions, according to a fall 2015 article from The Advocate.

Mathes said that the Financial Equilibrium Project will save a total of $4 million in costs by the end of the 2017 fiscal year.

The plan aims to eliminate 11 programs from Loyola’s budget, including programs that give grants for faculty research and training. Eighty-five other programs are to receive funding cuts, 20 will see increases in funding and the remaining 106 will stay unaffected over the next four years.

Discordant with the initial plan from the presidential advisory board, programs like Catholic studies and theater arts and dance will not be eliminated.

Beyond cuts in the budget though, the equilibrium project places an emphasis on raising Loyola’s enrollment, as more departmental cuts may be anticipated if the student body does not grow.