‘Equity New Orleans’ brings analytics to city decisions

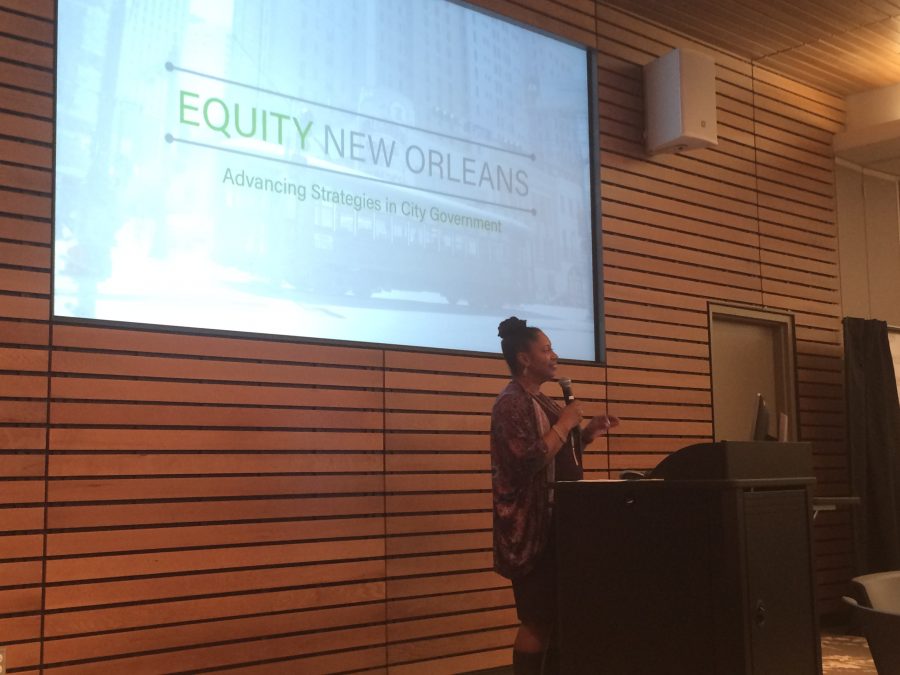

Judy Reese Morse, Deputy Mayor of Citywide Initiatives, speaks at the Equity New Orleans meeting on Tuesday, Jan. 17. The plan seeks to combat inequity in New Orleans by taking an analytic approach to decisions. Photo credit: Nick Reimann

January 31, 2017

“Data-oriented approach” was the theme of the night as members of the New Orleans community voiced their concerns over transportation issues at a meeting of Equity New Orleans.

As its name implies, the Equity New Orleans plan, started under Mayor Mitch Landrieu, seeks to bring equity, defined as providing equal footing and opportunity, to New Orleans.

“What I see here is a small number of people that participate a lot,” said Lisanne Brown, of the Bywater Neighborhood Association.

Brown hopes that the plan will end the cycle of the same group of people making decisions for the city of New Orleans, with the plan encouraging “broad participation.”

Analytics serve as the backbone of the plan, seeking to use demographic trends to determine the necessary steps to break down the existing economic, racial and class barriers it sees in the city.

Justin Augustine, Regional Transit Authority general manager, said that it is necessary to use analytics on broad projects such as Equity New Orleans, just as it is used in day-to-day activities at the RTA.

“A lot of people are afraid of data,” Augustine said. “Don’t be afraid of data. Embrace it.”

Augustine also said that data is necessary to make rational decisions, as decisions can no longer be “emotionally-based.”

Applying that to equity, according to Dwight Norton, urban mobility coordinator for the city of New Orleans, involves using that data to see where problems lie, and where the city should then prioritize investments.

“A car-dependent city is inherently inequitable unless everyone has a car,” Norton said. “How do we manage dependency and how do we make sure it’s for everybody?”

The issue here involves the growing number of jobs in downtown New Orleans, where rent is much higher than in surrounding areas, thus forcing workers to live farther from the city center, making them “dependent” on a car.

This is part of what Norton sees as a larger “technological dependency” that develops with new innovations.

Just as cars are now seen as a dependency, according to Norton, smartphones are now entering the realm of a dependency, as well. Norton cited the fact that only 64 percent of residents of low-income communities have smartphones, compared with 78 percent of the American population at large.

This puts those without smartphones at a disadvantage when it comes to access to Lyft, Uber and other ride-sharing programs Norton sees as becoming an increasing dependency.

This inequity is something the city hopes to avoid, though, as it uses demographic data to implement its upcoming bike-sharing program, described by Norton as “basically a one way hop on, hop off for bikes.”

Decision-making based off demographic data can be difficult, though, as Augustine said he has learned through his time at the RTA.