Bolivian vice president touts indigenous rights expansion to Loyola class

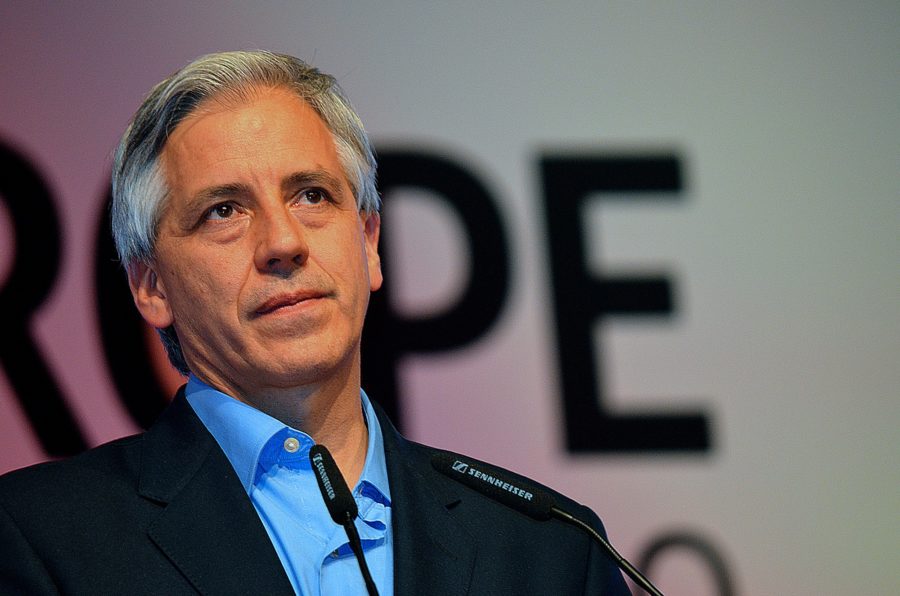

Álvaro García Linera, Vice President of Bolivia (2005-) sits at the IV Conference of the European Leftist Party in Spain on Dec. 13, 2013. Courtesy of Matilde Mamani from the Oficina de la Vicepresidencia of Bolivia.

March 15, 2017

Bolivian society is embracing multiculturalism and becoming more accepting, according to Bolivian vice president Álvaro García Linera.

Linera, who has served as vice president since 2006, spoke of his country’s recent changes during a Skype conversation with Professor Josefa Salmon’s Latin American cinema class, in collaboration with Monroe Library, Tuesday (March 14).

The Skype call came as an invitation from Salmon to Linera following the class’s viewing of La Nacion Clandestina (The Secret Nation), a movie detailing the struggles of an indigenous Bolivian man.

Salmon, a Bolivian native, first met Linera at a conference in Paris in 2002, where the two discussed issues facing the indigenous population in Bolivia.

“At that time, I was working with texts written by indigenous peoples and he was the first Marxist intellectual who connected with their social movement, so he saw through Marx what elements of Indian communities remained today,” Salmon said. “In 2012 I interviewed him about his major work Value Form and Community Form written while he was a political prisoner because he was a member of a guerrilla group that joined forces with indigenous leaders. We had remained in touch after that first meeting in 2002.”

Linera, who is not of indigenous descent, became vice president in 2006 after accepting the position from President Evo Morales, who is indigenous.

Since that time, Linera says, the administration had opened opportunities that never before existed for indigenous people, in large part due to “decolonization of the state.”

“The colonial relationship continued throughout time. The small population always ruled over the indigenous population,” Linera said. “Before Evo [Morales], an indigenous person could only ascend to be blue collar, construction worker or peasant. Blue collar was as high as they could go.”

Since Morales took office, constitutional changes such as a requirement to speak an indigenous language to hold public office, have increased indigenous representation in government, according to Linera.

Linera says that at least 53 percent of Parliament is indigenous, while 60 percent make up state assemblies. Half of Bolivia’s population identifies as indigenous, Linera said.

Despite Linera and Morales’ claims of progress, though, many international observers see the country’s situation differently.

In Human Rights Watch’s 2017 World Report, the country is cited for failing “fully to investigate alleged 2011 police abuses against protesters opposing a proposed highway in the Isiboro Secure National Park and Indigenous Territory (known as “TIPNIS”).” The report also criticizes the country for failing to fully receive free, prior and informed consent from indigenous groups for government projects impacting indigenous land and resources.

Another issue Bolivia is criticized for is the place of women in society, which was the subject of a question during Linera’s talk with the class.

Linera paused upon hearing the question, and then stated: “That’s a good question.” He went on to say: “We’ve come a long way in some things and not so far in others.”

Human Rights Watch lists women’s rights as a major violation in Bolivia, even though Bolivia’s constitution guarantees equal rights for women.

The Foundation for Sustainable Development says of Bolivia: “Perpetual rights violations by the Bolivian government against its people has fueled a palpable sense of desperation and anger throughout the country. Abuse of women and children is widespread and goes unreported or unpunished. Women’s individual, economic and social rights are inferior, severely limiting their ability to be agents for economic and social change.”

Linera says the administration is working to change this, though, calling domestic violence the next major issue they are working to tackle.

This was the final question Linera received during the Skype call, which Salmon feels was a great way of bringing real-world issues to her students.

“Reflecting on it afterwards, I think this is a good way of internationalizing the campus, and technology helps us in times of financial crisis or immigration impediments to bring people from overseas right to our classes,” Salmon said. “It is an experience that hopefully, the students will remember.”

Sidney Holmes contributed to this report.