Biology professor to conclude nearly 10-year research project in joint regeneration

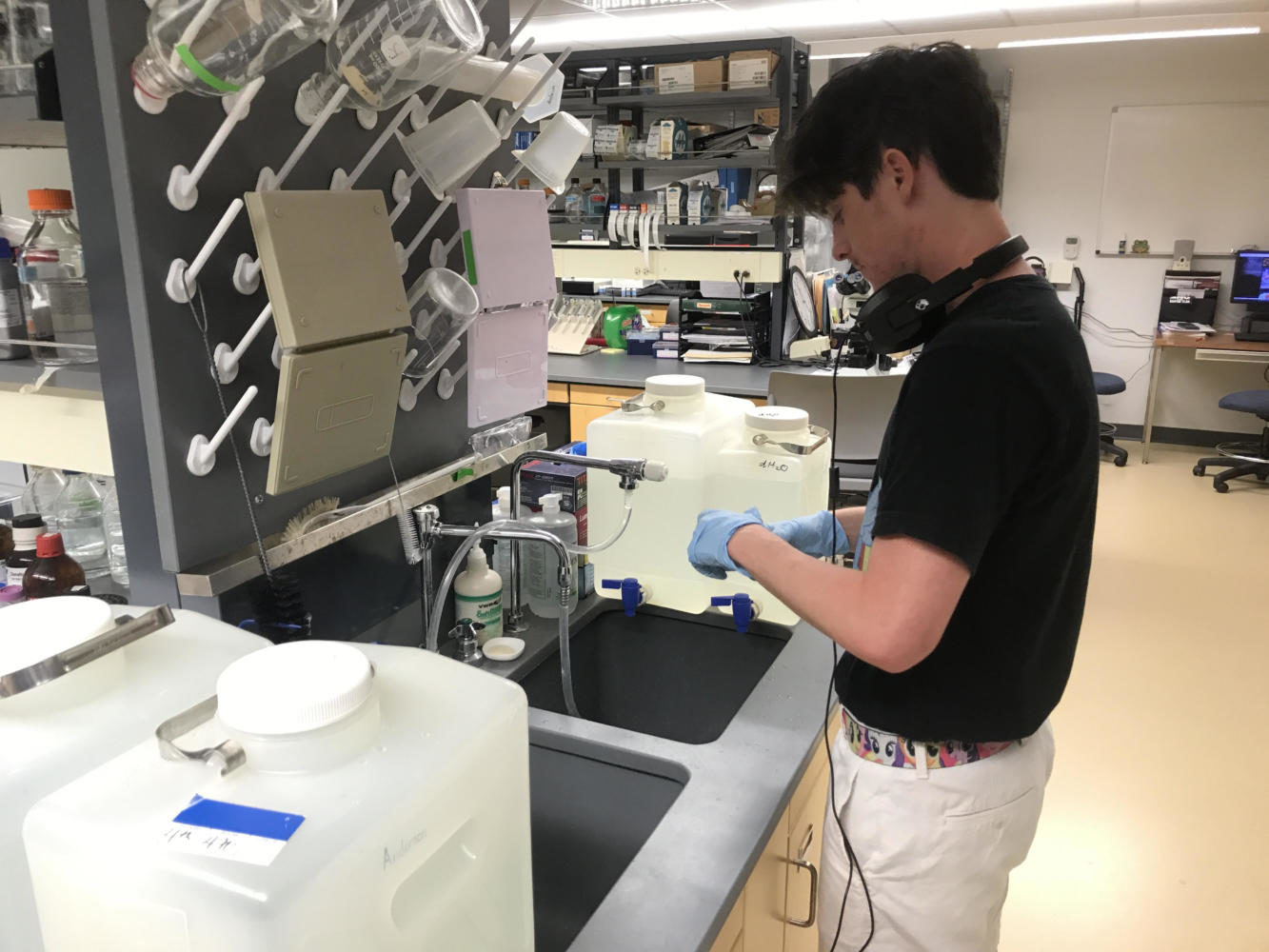

Research lab assistant William Brandt cleans equipment in the lab located on the fourth floor of Monroe Hall where Rosalie Anderson’s joint regeneration research takes place. The project involves cutting chicken embryos in the hope that research may one day help regrow human joints. Photo credit: John Casey

September 6, 2017

Loyola University Joint Regeneration Research in Action from John Casey on Vimeo.

As a child, Loyola biology professor Rosalie Anderson held a love for the natural world.

“I attribute my love for biology to, definitely, my family life,” she said.

Anderson grew up in Ocean Springs, Mississippi — the Gulf Coast town home to some of her grandfather, Walter Anderson’s, most famous works of art: colorful renditions of the region’s plants, animals and people.

“He called himself a painter,” Rosalie Anderson said. “He never called himself an artist, but he was definitely a naturalist.”

Anderson’s love for nature and biology led to her interest in joint regeneration research, which she has conducted at Loyola since 2009 and hopes to complete this school year. Through her research, Anderson — who teaches cells and heredity, investigating nature and additional higher-level biology courses — works closely with her students to study the joint tissue of chicken embryos.

Their goal? Improving human health.

“It’s kind of shocking when you go into science,” Anderson said. “At least from the textbooks, I felt like we knew most of the answers except for maybe cancer, and then I realized we don’t know as much as we need to know. Regeneration became one of them — or even how the limb develops, which is where I started.”

Anderson said she operates her research under two grants from the National Institutes of Health.

According to Anderson, determining what makes tissue regeneration possible could help people combat arthritis, aid athletes recovering from joint injuries and make certain prosthetic limbs more usable.

“To figure out how to get to the point where we can regenerate a joint, we need to find out what kind of conditions exist for that to happen,” she said.

In the lab, Anderson and her students cut out portions of chicken embryo joints. If and when a joint fully regenerates to close the gap left by the original incision, they study the environment of that embryo to narrow down conditions conducive to regeneration — a process Anderson says as “fun.”

Sometimes, Anderson said, she sees tissue regenerate in a matter of hours.

“We can look at the cellular level — what types of cells are replacing the joint — and we can look at the molecular level, which is what genes are being turned on to cause that to happen,” she said.

While Anderson initiated the joint regeneration research, she admits she has not done it alone.

Michael Dubic, biology senior, joined Anderson’s research team over the summer and said he — like each of the few dozen students who have worked with Anderson over the years — has a specific lab project he will tackle during his final year as an undergraduate student at Loyola.

“My task throughout the year is I’m going to be studying the placement of tendons and ligaments in the chicken embryos after the experiments we do,” Dubic said.

For Dubic, the Loyola baseball team catcher, Anderson’s research hits home.

Dubic underwent elbow surgery over the summer after tearing his ulnar collateral ligament. Because of his surgery and rehabilitation process, he sees Anderson’s joint regeneration research as a unique opportunity.

“There is some personal motivation there,” he said.

Dubic and Anderson both hope for promising results, allowing them to build on what Anderson said is a limited base of research on the subject. Dubic said he plans to present his portion of the research during the biology department’s annual undergraduate research symposium held during the spring semester.

“It’s one of the most rewarding things that I do here — having my students work with me side by side to try to answer these questions,” Anderson said.

Pat Burke • Sep 9, 2017 at 10:05 am

Amazing research, looking forward to the ongoing results this leads to. Hopefully it will usher in a new era for elbows, knees and much more.