Jesuit priest, former Maroon advisor Raymond Schroth passes away at 86

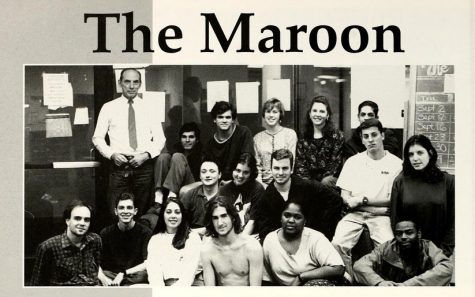

The Rev. Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. sits in his office at Fordham University in March 2017. Schroth served as advisor for The Maroon and a journalism professor at Loyola from 1986 to 1996. Schroth passed away July 1, 2020 at age 86. (Photo Courtesy of Michael Wilson).

July 14, 2020

The Rev. Raymond A. Schroth, S.J., a Jesuit priest, former journalism professor and advisor for The Maroon for 10 years died July 1, at 86 years-old. Schroth is survived by his nephew Kevin Schroth and his niece Cathy Bossolina.

During his 86 years, Schroth was ordained to priesthood, published eight books, taught at five universities, mentored Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists and wrote for several news publications including The New York Times Book Review, The Boston Globe, and America and Commonweal magazine, according to Jesuit USA Northeast Province’s website.

He was revered by former students as an educator, journalist, cheeseburger and martini connoisseur, traveller and, most of all, a life-long friend.

Michael Wilson, Loyola A’92 and a New York Times reporter, recalled Schroth the way Wilson did when he was a freshman at Loyola

“He was very tall, walked in a perfectly ramrod, straight posture, somewhat imposing presence on campus,” Wilson said. “You would see him walking around and he just always seemed to be deep in thought,” Wilson said.

But over time, Wilson would come to know Schroth as the man who he said changed his life. The man who married him and his wife, who baptized his children, spawned his love and career in journalism, and who Wilson met regularly for long dinners in New York City.

It was the moment Schroth let Wilson into his already full communications class that Wilson said changed his life.

“We spoke everyday and we would have lunch together to talk, we would have a beer together to talk,” Wilson said. “That sternness and seriousness that I ascribed, was all just on the outside.”

Schroth’s teaching style was described by Wilson and other former students of his as demanding, yet rewarding.

“He did not let you get away with anything that was lazy in your writing,” Wilson said. “He’s one of these people who taught me as much as my parents.”

Hank Stuever, A’90, said, however, that Schroth’s attention to detail and rigor was out of love.

“We paint this picture of him as being this steadfast, sturdy, vigorous, courageous, strict priest, but really he was very gentle,” Stuever said. “I think people forget to remember to say that he loved us. That’s why he worked so hard.

Stuever, who came to Loyola the same year as Schroth, esteemed him for treating students as equals and as if they “were on the verge of becoming a writer.”

“When I got to Loyola, I was 18 and he was 52, and I’m about to turn 52 now,” Stuever said. “It’s hard for me to think about what it must have been like for someone like him to have so easily mentored and befriended and become such a big presence in the lives of people who are 18, 19, 20-years-old.

According to Stuever, who is now a TV critic for The Washington Post, Schroth was the first to suggest to him that he could be a professional writer.

Neal Falgoust, A’99, also believed that the respect and attention Schroth had in him as a student impacted his life.

“He spoke to us like adults, he interrogated us like we were his equals. And, for a lot of us at that age, it was the first time that we had really been seen for who we were as individuals and not just as children of our parents,” Falgoust said.

In the spring of 1996, Falgoust, who was a rising sophomore at the time, joined Schroth on his road trip to Fordham University in New York where he taught for the next few years. He said he remembers the trip’s attention to the arts, how they listened to Nelson Eddy musicals, Edward R. Murrow’s World War 2 rooftop reporting in London, and spoke about journalism— its need for courage and empathy.

“I think he saw it as his last chance to teach me, to be a teacher for me, to be a role model for me,” Falgoust said about the road trip. “He used the opportunity to continue to instil those values that he always thought were important: integrity, courage, empathy.

Falgoust attributes his career as an attorney and his motto of “holding power to account” to Schroth.

Rose French, A’98 and journalist for the Atlanta Journal Constitution also said she owes her dedication to journalism to Schroth.

“I am so grateful for Father Schroth for so many things. Namely, teaching us all how to fight the good fight, to never give up even when the odds are not in your favor,” French said. “He’s a big reason why I continue to do journalism.”

Schroth was born in Trenton, N.J., to a journalist father and educator mother and was inspired to pursue both his parents’ career: journalism and teaching, which prompted him to become a Jesuit, according to a 2007 column from NJvoices.

“He really walked the walk and he lived desperately interested in the world, in culture, film, books,” Stuever said.

According to Wilson, Schroth’s personality informed his Jesuit identity and how he lived his life.

“In the same way it impacted his personality, his persona made him be a Jesuit,” Wilson said. “What made him a great teacher and great jesuit also made him a great journalist which is just a strive for perfection and a determined, determined work ethic.”

For his former students and those who come after them, Schroth’s impact and influence lives on.

“He has all of these students who are still working, whether they’re reporters at the New York Times or Washington Post or working as lawyers or teachers,” Falgoust said. “Every day that we go to work we are doing our service, we are writing his legacy.”