Loyola webinar educates on issues of incarceration and deportation

April 20, 2023

As migrants in the United States continue to face threats of poverty, incarceration, and deportation, scholars and activists say that for many members of these populations, solutions can be found in higher education.

Education can be a path to higher-paying jobs, allowing these individuals to escape cycles of poverty and criminal involvement.

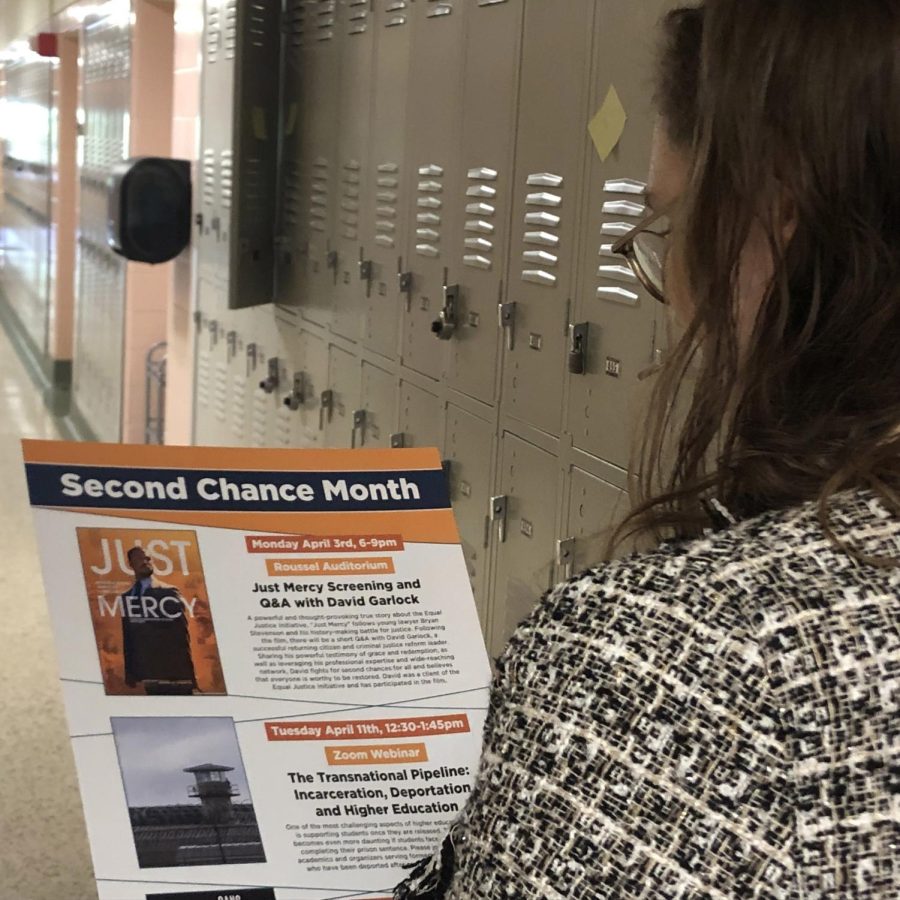

In honor of Second Chance Month, Loyola’s Jesuit Social Research Institute hosted “The Transnational Pipeline: Incarceration, Deportation and Higher Education,” an online panel featuring three experts dedicated to providing undocumented and incarcerated immigrants with opportunities in higher education.

“Bad apples”

Over half of the people deported to Mexico in the past year came from some kind of detention center, according to criminal justice and education reform activist Roberto Hernandez.

Hernandez is one of these people, as he was deported to Mexico after being raised and incarcerated in the United States. Hernandez personally experienced the lack of support and resources afforded to individuals in his position.

This lack of support, he said, perpetuates cycles of crime and poverty.

Often, English speakers deported to Mexico end up working for low wages in American-run call centers, Hernandez said.

Workers in these call centers “become slaves to the job,” he said. While they are able to make enough money to support themselves, there is no real room for upward mobility, Hernandez added.

When faced with this reality, people often return to criminal activity because it seems like a more viable means of financial support, Hernandez said.

Higher education may offer a different path, but, Hernandez said, the educational and governmental institutions currently in place make this goal difficult to achieve.

“We’re good people. We’re smart,” Hernandez said. “But we’ve been looked at as the bad apples being returned from the United States.”

Hernandez added that, because of this negative perception, he had difficulty transferring academic credits he received in the states.

He was told that he must essentially “start over” his high school education after arriving in Mexico, despite receiving high test scores.

The systems in place designed to support recently deported individuals seeking education do not reflect the lived experience of a majority of those individuals, said Ricardo Zepeda, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Guadalajara whose research focuses on marginalized communities in higher education.

Most of the programs are designed to serve young students in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program with high grades while the majority of people deported to Mexico are older and have been previously incarcerated, Zepeda said.

Zepeda said that his recent work, in collaboration with Hernandez, centers on raising visibility for these issues and communities.

“We are trying to shift the narrative about those who are being deported,” said Danny Murillo, co-founder and associate director of the Underground Scholars Program at the University of California at Berkeley.

This will help end the cycles of deportation and incarceration, which often haunt immigrant families, he said.

“People who come from marginalized communities and excel are not only bringing something to their own lives, but their communities,” Zepeda said.

Collaboration and support

Murillo said collaboration is important. He said that much of the work and research being done has to be a collaborative effort between American and Mexican scholars. Murillo said that his work, in relation to Zepeda and Hernandez’s efforts in Guadalajara, is supportive.

“I want to continue to create opportunities,” he said, specifically noting the potential and importance of student housing and technological expansion.

Murillo said he plans to transform his personal property, in Guadalajara, into a transitional home for recently deported people. He said that he hopes that this location could translate into a form of free student housing for these same people.

During the panel, Murillo spoke about his efforts to make connections within the growing tech industry in Guadalajara. As the industry expands, so does the area’s job market.

Zepeda said all three panelists are currently working with Global Purdue to establish a certificate program catered toward people who have experienced deportation. These efforts include collaboration with Mexico’s Secretary of Education to further expand the program.

After the webinar concluded, Loyola’s JSRI sent out further resources discussing incarceration and deportation. These included links to The Education Justice Project, which provides scholarships for people deported to Mexico, and Hernandez’s organization, Grupo Destino Libertad Servicio Unidad Recuperación.

“American institutions hold responsibility for this issue,” Hernandez said. “It is important for Americans to support the efforts of those facing these issues.”