Suddenly, the struggles Torry Beaulieu weathered on a lackluster 5-13 Wolfpack basketball team his freshman year didn’t matter at all – not the semester fouled up because of Hurricane Katrina, not the 87-41 loss to Tulane, not that he was on a team with a losing record after having won a high school state championship on an undefeated team the year before.

On Mother’s Day weekend last May, Beaulieu, history sophomore, received the nightmarish phone call everyone dreads the most.

Ryan Francis, the guy Beaulieu called his “blood brother,” had been shot and hospitalized.

A faceless man, someone neither Bealieu nor Francis had ever known or had ever met in their lives, took to the Baton Rouge streets one early Saturday morning in May and violently shattered their brotherly bond.

Ryan Francis flew back from a successful freshman season, playing for coach Tim Floyd and the University of Southern California, the week before Mother’s Day to visit his mom and spend some time with friends in Baton Rouge.

“We worked out from Tuesday to Friday,” remembered Beaulieu, who then had just finished his first season as the starting point guard for the Wolfpack.

“He was showing me all the stuff they do in California, in Division I, and I loved it. I was just eating it up.”

After a long week of working out – they practiced so hard against each other they’d almost fight, but that’s how they liked it. “It was like iron sharpening iron,” Beaulieu said. The two wanted to blow some steam off.

It was Francis’ first time back in town, and because it was Mother’s Day weekend, a lot of their friends were in town and wanted to get together.

“A lot of people hadn’t seen him, so we decided to have a party,” Beaulieu said.

Everyone reconnected at a club called the Plaza Lounge.

As the party wound down, according to a USC spokesman, Beaulieu was supposed to take Ryan home – but Beaulieu lived across town.

So Francis switched rides.

“He ended up leaving with his cousin,” Beaulieu said, wiping his hand down the front of his face.

“We were supposed to work out in the morning at 11, so I said ‘All right,’ and left.”

It was at home where he got the call from the driver of the 2006 Chevy Impala Francis left the party in.

While they stopped at an intersection less than three miles from Francis’ home, 19-year-old D’Anthony Norman Ford pulled up in a 2000 Mistubishi Montero Sport and blocked them in.

According to detectives, Ford had recognized the driver as “someone with whom he had an earlier dispute.”

Ford sprayed the car with gunfire as they tried to speed off.

“He only shot at Ryan,” Beaulieu narrated, shaking and tense.

Beaulieu remembered rushing into the hospital, hugging Francis’ mother, the only thought he could hold together being, “I hope he doesn’t die.”

It wasn’t the first time Beaulieu was called to the emergency room on Francis’ behalf.

En route to the hospital, he remembered how Francis broke his jaw and his wrist their junior year at Glen Oaks High School in a car accident, and how he miraculously “came back to be the best basketball player in the state.”

Beaulieu, who never had an experience with death, hoped he could pull through just one more time.

Francis, however, died at 3:40 a.m. at Baton Rouge General Medical Center.

Six hours and 28 minutes later, 20 minutes before Francis and Beaulieu were supposed to meet up to work out, police arrested Francis’ killer.

“I had never seen him before in my life,” Beaulieu muttered.

‘EXEMPLARY’

One month before Beaulieu signed to play as a scholarship athlete at Loyola, he and Francis had topped off the season of their lives with the 2005 state champion Panthers of Glen Oaks High.

“Their teamwork was exemplary. They were the team that no one thought would win – they had no tall post players,” said Robin Fambrough, a sportswriter for The (Baton Rouge) Advocate that chronicled the team’s fabled season. “They played lights out defense from endline-to-endline and they knew where their spots were on the floor.

“They (played) teams like a trombone.”

Francis was the leader of the orchestra, directing the tempo of his team’s disciplined movements on the floor. When his options dwindled, he’d pinpoint a pass to his best friend’s trusted hands.

“Torry drove well and he could shoot when he had to. They had their comfort zones,” Fambrough observed.

Beaulieu, who won district MVP his junior year, knew where to go on the floor – his best friend, district MVP their senior year, knew his tendencies and strengths and always put him in a position to do what he does best: either score by driving to the hoop or by knocking down a jumper because of the space he afforded himself with a cleanly-run route off the ball.

“They were very bright players. They knew what they needed to do in the system they were in,” Fambrough said about the master tandem that operated in a system that, with no inside threat, relied on their guards.

It was because of their lack of size that no one gave Glen Oaks a chance against Denham Springs High in the Louisiana High Schol Athletic Association/Louisiana High School Coaches Association Hall of Fame game played before a packed Pete Maravich Assembly Center that February on LSU’s campus.

Denham Springs counted on athletic phenomenon Tasmin Mitchell – now an LSU Tiger best-known for his roles in beating No.1 seed Duke and No. 2 seed Texas in their improbable run to the Final Four last year.

“They had been on a preview show (on a radio station in Baton Rouge) and Tasmin was saying how we had no chance against him. I was like, ‘I don’t know,'” Beaulieu said, chuckling.

Glen Oaks assaulted the PMAC court and kept the game close, somehow surviving a game-high 26 points from Mitchell and finding themselves in a position to steal an upset late.

Tied 46-46, the buzzer seconds away from sounding, Francis knifed to the basket and shot.

“I saw (the ball) bounce on the rim and I thought it would go in,” Francis told The Advocate. “I just knew it had to.”

It did.

“We called Tasmin back and talked some noise (trash),” Beaulieu recalled.

“Once again, our guard play with Ryan Francis … (and) Torry Beaulieu … carried us,” Glen Oaks coach Harvey Adger said after the game.

When Glen Oaks found itself in the state tournament, Fambrough remembers that everyone doubted them because they were an undersized team lacking a conventional post threat.

A Shreveport sportswriter watched Glen Oaks play after a number of powerhouses had been upset in the early rounds, and with all the confidence in the world told her, “That’s the best team here.”

The writer was right – Francis, with four assists, bucketed a game-high 22 points and Beaulieu added 16 in the championship game against Bossier high to perfect their season at 36-0.

“Man, those high school days – those were the best of my life,” Beaulieu said.

FRANCHISE AND T

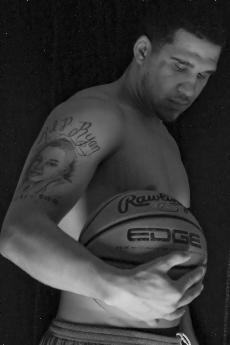

Beaulieu sat straight, tense in a sofa outside the Orleans Room last week. It’s been seven months now, but he still trembles as he speaks about what happens, as he lifted his sweatshirt and proudly explained the tattoo on his right arm: one of Francis’ face, with “R.I.P. RYAN” arching over it, the dates of his brief life (3-17-87 – 5-13-06) underlining the portrait.

On his left wrist, Beaulieu wore a USC red-and-yellow wristband that read “In memory of Ryan ‘Franchise.'”

“Franchise,” who called Torry “T,” is what Beaulieu called Francis.

T smiled timidly, chuckling nervously as he narrated how they met on an Amateur Athletic Union state championship team for 10-and-11 year olds but how his first memory of Franchise came before that.

“I played for this team called the Bucks and he for a team called the Cardinals. It was the ‘brat league’ championship game,” T remembered.

It was near the end of regulation.

“My first experience with Ryan Francis, I came down, crossed over and he ripped me and went on to make a lay-up and they won the game,” he said. “That’s what I first remember of Ryan Francis.”

They remained friends through high school, and by the time ninth grade rolled around, it seemed that Franchise stayed at T’s house all the time.

“We were just doing what high school boys do,” T said. They watched movies, played basketball in the driveway or on NBA Live for the Playstation 2 and hounded girls.

Even when Franchise opted to play PAC-10 ball for Tim Floyd and the University of Southern California and T came to coach Michael Giorlando and Loyola, they spoke everyday.

“Even when he was in Alaska (on the road), we talked,” T said, “I was asking him if (college ball) was that much different. He told me, ‘Yeah, get ready. It’s much different, T.”

Franchise was right: the two journeyed down vastly different seasons.

On Dec. 21, Beaulieu had just completed his first practice with the Wolfpack – months late because of Hurricane Katrina.

That same day, thousands of miles away in Los Angeles, Francis plugged the North Carolina Tar Heels, the defending national champions, for 12 points and seven assists in a 74-59 upset win.

As Francis and USC thrived, Beaulieu and the Wolfpack started their season lagging, going 2-7 before getting trucked 87-41 by Tulane at Fogelman Arena on Feb. 6.

“There were nights I went to my room and just wanted to cry,” Beaulieu remembered. “I had never gotten so badly beat before (like I had against Tulane) in my life – in my life.”

But fourteen days later, his best bud Franchise amassed 12 points and four rebounds against USC’s nemesis – the UCLA Bruins, an eventual finalist for the 2006 National Championship game.

He marked Jordan Farmar, now a Los Angeles Laker, and minimized him into a non-factor that game.

That cheered Beaulieu, Francis’ biggest fan, up. “You can ask Luke (Zumo) and all those guys. I was watching that game, screaming and hollering at the TV, acting just like I would if I was there,” he remembered.

Basketball-wise, things brightened up from there. In the first round of the GCAC tournament, Loyola upset No. 23 Mobile 68-66, Beaulieu’s fondest freshman memory.

“Oh my God. I had the best game of my life,” he said, nodding his head. Beaulieu ventilated Mobile for 18 points and put the game out of reach by hitting three free throws in the game’s closing moments and propelled the ‘Pack to the conference semifinals.

Two months later was Mother’s Day, and Francis’ death put his freshman basketball struggles and small taste of success into perspective.

Beaulieu said, “I’d give anything,” and paused, before he raised his voice and spoke faster. “I’d give up everything, because I can tell you now that I’d rather have him playing over there at USC than for me to be playing here right now. And I love it here.”

“EVERYWHERE WE WENT, WE WERE TOGETHER”

D’Anthony Norman Ford’s aimless anger violently broke the brotherly bond that Beaulieu and Francis loved.

But love’s a hard thing to let go of, especially when it ends abruptly and because of circumstances outside of human hands.

Beaulieu keeps Francis’ memory close with him in his day-to-day life at Loyola.

In between practice, games, class and socializing, he speaks to Francis’ mother on the telephone three times a week.

Reverently and proudly, he dons that red-and-yellow “Franchise” wristband she had made.

“(Coaches) don’t let me play with it on, but I wear it at practices, at warm-ups, at shootarounds – right up until tip-off,” he said.

To hear Torry explain how things were between him and Ryan, it’s like they were – for lack of a more exact expression – brothers.

“If you saw me, you saw him. Everywhere we went, we were together,” he said.

Franchise and T – side-by-side.

And side-by-side they remain – Franchise alive in Bealieu’s heart; Franchise tattooed on Beaulieu’s arm, on the court with him at every game and out in the world with him each waking moment.

Ramon Vargas can be reached at ravarga1@loyno.edu. Michael Nissman contributed to this report.

Wolfpack point guard Torry Beaulieu, history sophomore, posts up against a Wiley College defender. Though his team struggled his freshman year, nothing compared to the death of Ryan Francis, whom he called his “blood brother.” (Victoria Lodi)

Ryan Francis, Torry Beaulieu’s best friend, drives to the rim and executes a layup when they both played on a 36-0 Glen Oaks Louisiana state championship team in 2005. Together, they upset Denham Springs High and Tasmin Mitchell, an LSU Tiger that helped push them through to the Final Four in 2006. (Courtesy of The Advocate)