In her stint as a journalist during the war in Iraq, Margaret Kennedy stood on the sidelines as parents looked through plastic bags containing what might be their dead son’s clothing, she said.

She said she saw a nurse on a military ship sob as she spoke about the young children she had left at home so that she could serve her military duty. She watched as newspapers sprang up in Baghdad, schools reopened and weddings took place.

She saw it all through the lens of a video camera.

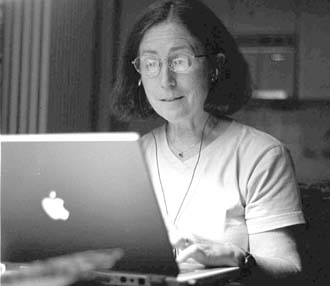

Kennedy, a video journalist for international broadcasting service Voice of America, spoke about her experiences as an embedded journalist with the Navy and as a reporter in Baghdad on Tuesday evening in Nunemaker Hall.

Kennedy has worked for the Voice of America for more than 30 years in many positions, including senior news editor and African editor. In the 1990s, she learned video journalism.

Six months ago, Kennedy became one of 700 embedded journalists when she traveled to the Persian Gulf to shoot the war zone.

Getting information was not always easy. Kennedy said that when the reporters boarded the ship, they became a part of the military.

They ate the same food, slept in the same bunks and lived in the same kind of quarters as the troops on board did. They were also expected to follow military procedure.

“It was a very controlled situation,” Kennedy said. “Somebody has to let you in and tell you what they’re doing. If you can’t get the picture, you can’t get the story.”

Kennedy also said that her work area on the ship was below the thin landing strip. At times, the noise was so loud that she couldn’t mix audio for her stories.

“There was no way to escape it (the noise),” she said. “No matter where you went on the ship, you were always susceptible.”

After the war ended, some first-string journalists went on to Baghdad.

Most of the embedded journalists, including Kennedy, went home for a while to recover from the stressful trip.

“After that kind of experience, you want to go home. You want a hot bath,” Kennedy said. “Most people wanted a beer.”

In May, Kennedy set out for Baghdad to cover the reconstruction efforts. Her experience there was completely different from her time with the military, she said. The country was very disorganized, she said. There were no police or traffic laws in place. There were no banks, so everyone had to carry cash.

“You might as well have put a sign on your forehead that said, ‘I have lots of money,'” Kennedy said. “You had to carry it all, because there was no other way to protect it.”

In Baghdad, Kennedy reported on the way that the country was coming together after Saddam’s rule. The road to repair was not easy, she said.

“Hitler’s rule in Germany lasted one third of the length of Saddam’s rule in Iraq,” she said. “Imagine what it is like. Everyone has lost relatives to torture and murder. Everyone has been spied on. You don’t go back that quickly.”

However, Kennedy said that she visited churches, schools and hospitals to get the story that wasn’t being told: the Iraqi people’s return to life.

“There were a lot of sad things,” she said. “But real newspapers were starting up again. I saw joyous weddings. There are people getting paid for their work now. This is a capable society that has realized that 150,000 American soldiers cannot run Iraq.”