Wednesday, Sept. 11, signified the twelfth anniversary of an attack that changed the course of U.S. immediate history.

Students and experts on Islam disscussed the question of the current state of prejudice against Islam in the U.S.

Behrooz Moazami is an assistant professor of history and teaches in the Middle Eastern peace studies program. He described the hatred of Islam as “a type of organized racism.”

“Islamophobia is hatred of Islam and those who follow Islam itself. It is a fascistic movement very similar to anti-Semitism,” Moazami said.

Moazami said that stereotyping and generalizations of Islam and Arabs take form as prejudice. Adil Khan, assistant professor of Islamic Studies, said that limited exposure to Islam leads to misunderstanding the religion and grouping people together by perceived race and religious affiliation.

Moazami said that he saw an upward trend in hatred of Islam after 9/11. He said that he also saw hatred of people that appear Muslim or Arab, regardless of actual cultural identity or religious affiliation.

“I do remember very well on 9/11, there were many drivers in New York that were Indian Sheik. They were beaten because they were mistaken for Muslims,” Moazami said.

Adil said news media intensified hate towards Islam in America with immediate reactions to the 9/11 attacks.

“What 9/11 did is that it made everyone aware of Islam and of Muslims, but much of the coverage was negative,” Adil said. “The measure of this was for example, attacks on mosques.”

Hamza Khan is an economics freshmen who emigrated from Pakistan more than a decade ago. Hamza said that he felt the negative effects of prejudice fueled by the media following 9/11.

“Kids would call me terrorist and my friends’ parents would treat me differently,” Hamza said. “They thought that I was going to try to convert their kids or something, and they acted afraid of me.”

Simon Whedbee, co-president of the Student Peace Initiative and English literature junior, described the pressures of generalizing felt by Muslims because of prejudice.

“They feel a lot more pressure, that their actions reflect half of the world,” Whedbee said.

Hamza said he also experienced prejudice while out with his family.

“My family and I would be stared at just while grocery shopping, and you can tell when someone is treating you differently from other people,” Hamza said.

Hiba Elassar, biochemistry junior who grew up in a Muslim household, said that she notices people make instant judgements and assumptions about her personality because of her hijab.

“Often I feel like I walk into situations where people have already made snap judgments about my personality and my abilities based on my hijab,” Elassar said in an email.

Study abroad programs at Loyola allow students to gain better understanding of global cultures. Like all mainstream world religions, Islam takes various forms according to different parts of the globe. Adil said he believes exchange programs may only allow for a limited scope of grasping Islam.

“You have people who may have spent a certain amount of time in a country and they experience certain things, but that is still very limited,” Adil said. “It’s like if an Egyptian came to New Orleans. While, yes, that is American, it is not a reflection of America as a whole.”

Whedbee said that even accidental stereotypes can come from limited exposure to Islam and may take a form of prejudice.

In 2010, the hatred of Islam was an especially present topic in the news when New Yorkers demonstrated against the Park 51 project that planned to build a Muslim cultural center and mosque two blocks from ground zero. Whedbee said that a very small minority of extremists is given the power of rhetoric by the international community and so, it has the opportunity to create havoc and misrepresent a majority of Muslims.

“After Sept. 11, several Muslims were unlawfully, unethically imprisoned in the name of national security for ‘relations’ to Al-Qaida and other so-called ‘Islamist’ groups,” Elaasar said in an email. “Many were American citizens, and had their rights yanked away from them based on little or no evidence. And I’m not just talking about Guantanamo.”

Whedbee said that Islamic extremists are given to much focus and they misrepresent the Muslim majority.

“9/11 has given radical Islam an international microphone and international stage. They have become the center focus in terms of what’s going on in that region, or going on in that religion, regardless of the majority of people who identify with Islam,” Whedbee said.

Moazami and Adil said they have not seen or experienced this prejudice at Loyola or in the New Orleans community.

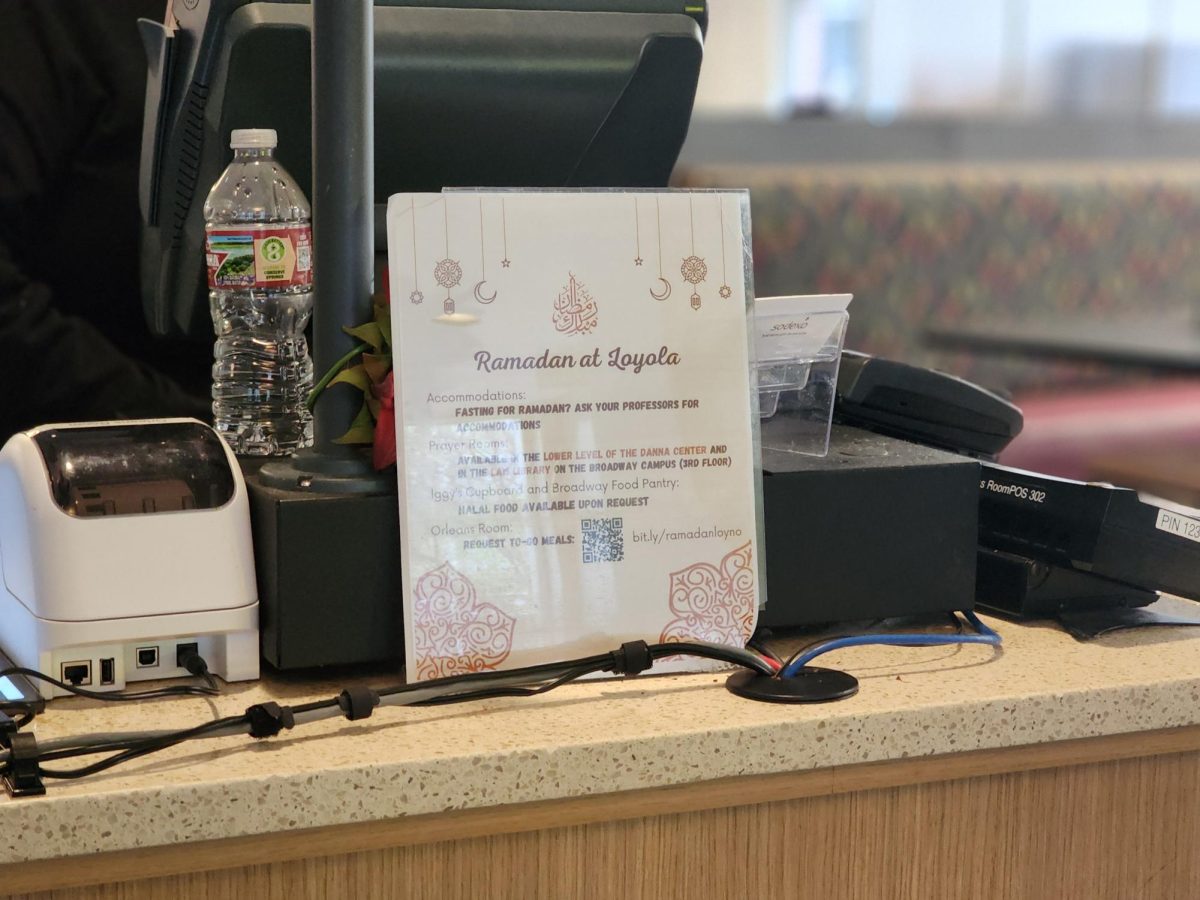

“I have not seen or experienced any Islamophobia at Loyola,” Moazami said. “The Jesuit character of the school allows people of divergent religious traditions to practice freely.”

Whedbee said he believes that the best way for the community to address prejudice, social injustice and ignorant stereotypes that breeds hatred is through intellectual discourse and interfaith education.

“When you get to know a person, and get to work with a person, you have a hard time demonizing their beliefs, you have a hard time not respecting his or her point of view,” Whedbee said.

Moazami said he believes that the hatred of Islam is more than a societal prejudice and it is also a part international and domestic political discourse.

Jessica DeBold can be reached at [email protected]

Associated Press contributed to this story.