Ashley Howard

Assistant professor

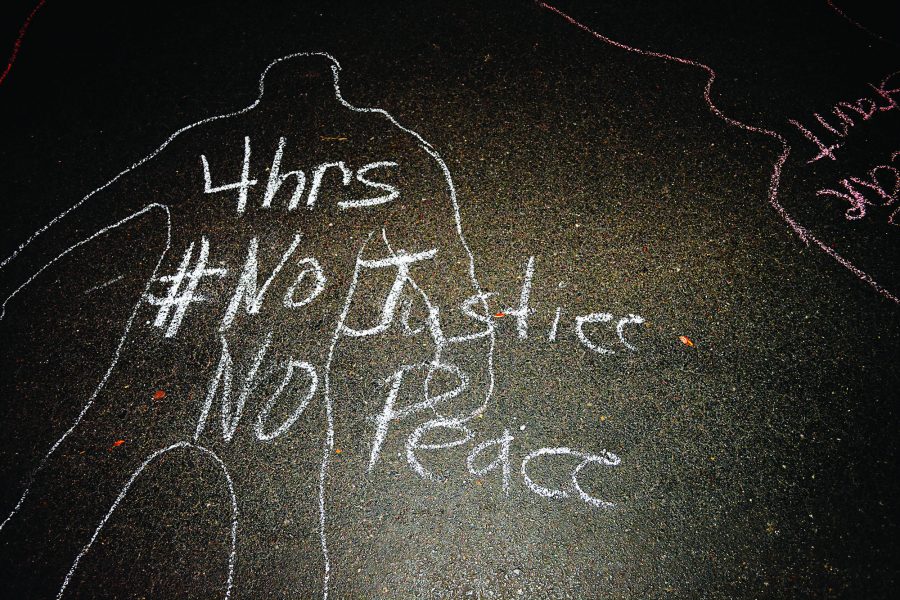

The growing #BlackLivesMatter social movement draws strong, often polarizing opinions in discussions across the nation. What is certain, however, is that citizens challenging the status quo represents the norm, not an aberrancy, in American history. Historian Gary T. Okihiro argued in his 1994 book Margins and Mainstreams “the core values and ideals of the nation emanate not from the mainstreams but from the margins.” Whether attendees at the 1848 Seneca Falls Conference, fed-up bar patrons at the Stonewall Inn or incarcerated men at Attica Prison, those on the outside of society have forced the mainstream to expand equality’s reach. One of these most persistent groups bringing challenges to this country’s injustices are black Americans.

For nearly four hundred years, African Americans and their allies mobilized towards, petitioned for and dreamed of a more inclusive nation. These visions, just like blacks themselves, are multifaceted and heterogeneous. Challenges to racial injustice brought by African Americans have comprised numerous tactics and strategies including cultural, territorial separatist, Marxist, conservative, feminist, nationalist and every ideology in between. The texture and shape of protest morphs over time, but each foray seeks to bend the arc of the moral universe towards justice. What remains constant is the vision of an America that is more inclusive and less hostile for all of those inside its borders. The #BlackLivesMatter movement marks a significant shift from previous activism but remains true to the spirit of black resistance.

As racism and oppression continue to take different forms, activists must also remain nimble. Retreating from antiquated Civil Rights organizational models, #BlackLivesMatter innovates to mount a successful campaign in the twenty-first century. Whereas previous social movement organizations relied on extant community resources like churches, fraternal organizations and lodges, #BlackLivesMatter forms new communities through social media. In the employment of Twitter, Facebook and Periscope, activists are able to mobilize events, connect in solidarity with international movements and offer counternarratives to what is broadcast on the news. The modern movement also employs a decentralized structure or “leaderful” movement, allowing activists to mount multiple resistances nationally without a central-Messianic figure. Despite these striking differences, the 6-prong platform of The Movement for Black Lives echoes previous demands put forth by black activists, only with updated solutions for the current moment.

We are in the midst of an important social movement. One that strives to tie the local to the national, and the national to the global. One that conceptualizes oppression intersectionally, not unilaterally. One that links to the past, while blazing into the future. Those silenced in America consistently seek out ways to make “a more perfect union.” Yet, the responsibility is also on us; as Desmond Tutu wrote “to be neutral in times of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” Rooting ourselves in our shared Jesuit values, we must all work for a more just world, blurring the lines between margins and mainstream.