Lack of professors of color impacts students

If you take a class at Loyola, there is almost a three in four chance that your professor will be White.

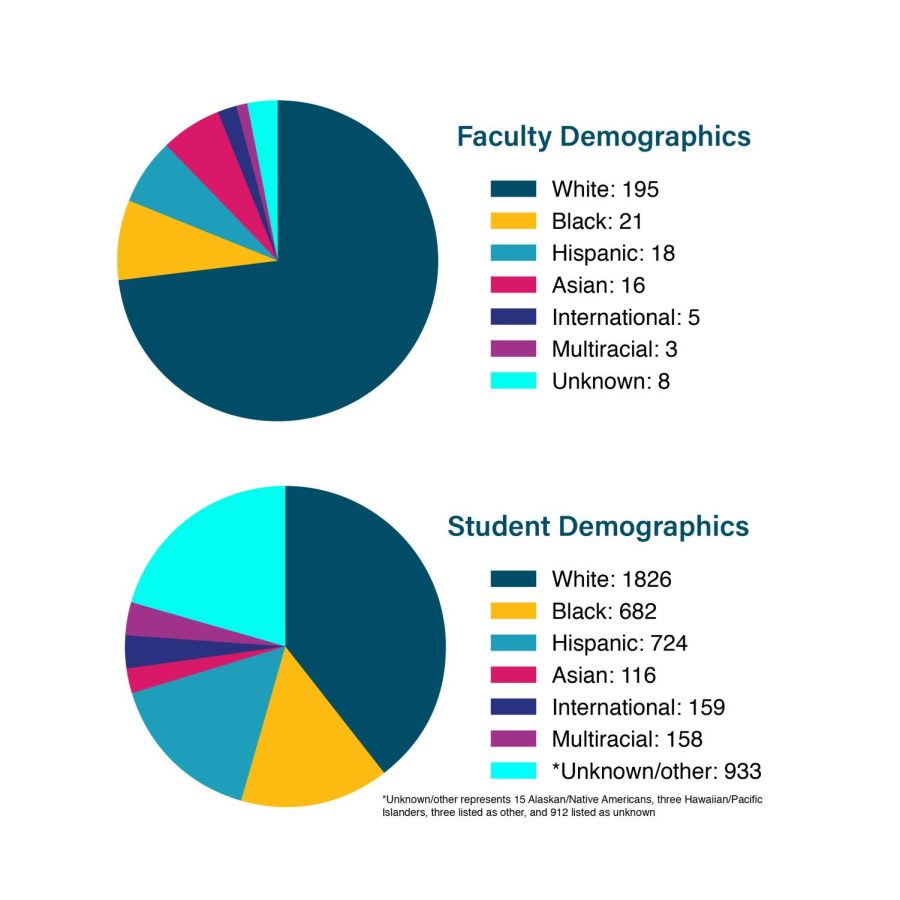

However, despite the fact that Loyola’s student body is only 39.7% White, White professors make up 73.3% of full-time faculty, according to Rachel Hoorman, vice president of marketing and communications. Students of color said they feel the disparity.

Vairleene Einstein, an environmental studies senior who is Black and Haitian, said she has never had a Black professor in her nearly three and a half years at Loyola.

“This is still shocking considering the population makeup of New Orleans,” Einstein said. “So it is bizarre when you see that the majority of the faculty are White.”

Black professors make up 7.9% of the faculty body, yet Black students make up 14.8% of the student body, according to Hoorman.

Einstein said the lack of professors of color has affected her personal experience at Loyola and impacts the content and focus of courses on campus.

“Oftentimes, we’ll overlook the marginalized groups, which just leads to the White-centric education that we keep receiving,” Einstein said.

Alvin Hamilton, a digital filmmaking junior who is Black, said although he feels somewhat represented on campus, he feels that Black students could use more representation at Loyola.

Hamilton said it’s hard for people of color to aspire for careers without seeing representation in the fields. A more diverse faculty could help with that problem, according to Hamilton.

“You’re just like, ‘Can I even get in an industry?’ Like, ‘Is this even a place for me?’” Hamilton said. “So that representation could go a long way.”

Hispanic and Latine students have similar experiences with the lack of professors of color they see on campus.

Crystal Pohl, a Latine philosophy senior, has only had one Hispanic professor, which was in a Spanish class. She said this has affected her overall experience at Loyola.

“Whenever I’m in class, they’re never talking about things from a Hispanic perspective or from a Black perspective,” said Pohl. “Usually it’s always under a White perspective.”

Pohl said when she was learning about Loyola before enrolling, the promotional materials showcased how diverse the school is. She said that her experience regarding diversity has not reflected what she expected based on the brochure.

Hispanic professors are in a similar position to Black professors in which they make up 6.8% of the full-time faculty with Hispanic students being 15.7%.

Lydia Mendoza, a psychology junior who is Hispanic and White, said that being half-White is a large factor in feeling represented on campus.

“I am incredibly proud of my Hispanic heritage, and I don’t feel like there’s enough professors or faculty to make me feel like both sides are represented,” Mendoza said.

Mendoza also said that the few Hispanic and Latine professors on campus are often White.

Mendoza feels that the university needs to do a better job hiring professors of color in all areas and that it needs to represent its students.

“If you want to be a Hispanic-serving institution, you need to act like it. And you need to hire people that are going to make it that way. And you need to hire people that are going to serve the rest of the student body,” Mendoza said.

Hamilton, Pohl, Mendoza, and Einstein have all had a class about an underrepresented group taught by White professors. All said that while they felt their professors were qualified to teach the course, the experience would have been better with a professor from that background.

“I think the education was very great. It was just limited,” Einstein said, “We had to get extra resources to get the minority perspective.”

“When it comes down to it, this is a White lady telling me about an entire continent’s history,” said Mendoza. “What does she know about it that she didn’t learn from a book, or didn’t learn from being there?”

Besides White faculty, the only other group that outpaces its representation in the student body is Asian full-time faculty at 6% compared to 2.5% of students.

Kedrick Perry, vice president of equity and inclusion, said that having someone that looks like you as a professor helps to motivate you and reduces imposter syndrome in students, especially those in underrepresented groups.

“The more you’re able to see people who look like you achieving great things, the more you’re able to see yourself achieving those things too,” Perry said.

Tanuja Singh, provost and senior vice president of academic affairs, said many factors play into the disparity between White professors and professors of color. She said she has not seen that this disparity has negatively affected students.

Perry said that the data shows that students may not be affected academically, but that it can affect their social aspirations.

“What it does affect is just being yourself in those roles, which can affect motivation, which can affect imposter syndrome, and those types of things,” Perry said.

Singh said that Loyola, like other universities nationally, looks for terminal degrees when hiring faculty. A terminal degree is the highest degree available in a particular academic field, like a Doctor of Philosophy or a Master of Fine Arts degree.

She said the number of people of color getting those degrees is significantly smaller than White Americans.

“While there has been a lot of progress made, the number of people graduating with those degrees is fewer. So the competition to get those very highly qualified faculty is very high,” Singh said.

Singh said another factor impacting faculty diversity was the hiring hiatus Loyola went on due to the financial deficit. She said having a traditionally White faculty body and a pause in hiring makes increasing diversity difficult.

“The percentages can’t change unless you’re making significant hiring decisions,” Singh said.

Despite the challenges, Singh said hiring diverse faculty is a big priority for Loyola. She said the university is training the faculty in implicit bias in order to help with hiring.

“Not only do students want this to happen and see diversification of faculty, but staff and the faculty want it as well, and everybody is really working towards it,” Perry said.

Singh said that the university is a member of the Ph.D. Project, which aims to diversify business faculty by helping people of color get Ph.D.’s. This membership gives the school the ability to post job listings on the site, according to Singh.

Singh said that nine of the last 21 full-time faculty members the university hired are “non-White candidates.”

“As our population grows more diverse, one of the biggest things that we pride ourselves on is how diverse Loyola is as a university,” said Singh. “I would be equally proud when we could say we are a very diverse university in terms of our faculty as well.”

Minority professors currently make up 21.8% of full-time faculty at Loyola, according to Hoorman. Nationally, 24% of professors were “non-White” in 2017, according to Pew Research Center. This puts Loyola 9.1% below the 2017 national average.

“Unfortunately this type of change does not happen overnight, and it is more a marathon, than a sprint,” said Perry. “But I think the impetus and the will is there for this change to happen.”

In spite of the efforts to diversify Loyola’s faculty, many students still do not feel represented on campus.

“Students want the chance to be heard and be open with their professors, but it’s just not the same when they’re not coming from the same background,” Einstein said.

Gabriela Carballo is the editor-in-chief for the Spring 2022 semester. A senior from Miami, Florida, she is double majoring in environmental...

Andrew Lang is the Spring 2022 webmaster. He is a mass communication senior. He’s previously served as design chief, copy editor, sports editor, staff...

Kat Kelsey is a senior graphic design major and art history minor from Fort Lauderdale, Florida. She has contributed illustrations to the paper for the...

Brittany Gonzalez • Apr 10, 2024 at 2:21 pm

Amazing article! I am going to use this article to discuss representation in schools with my students! 🙂