Failed coup “threatens” Brazil’s democratic values

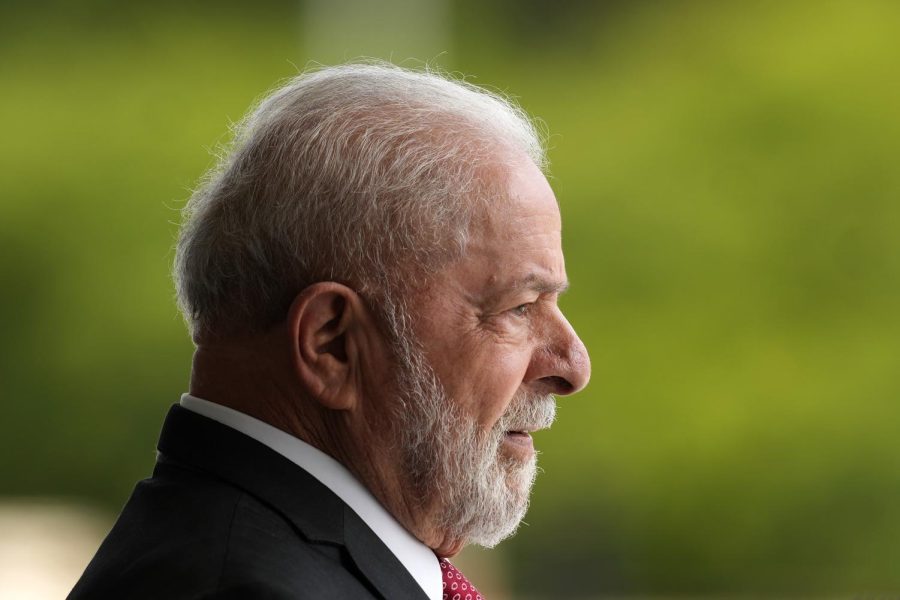

Brazil’s President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva waits at the Planalto Palace, in Brasilia, Brazil, Monday, Jan. 30, 2023. The palace was stormed by Bolsonaro supporters only twenty two days prior. (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres)

February 2, 2023

Many Brazilians, like Loyola Latin American history professor Tiago Fernandes Maranhão, were not surprised about Bolsonaro’s supporters attempting an attack on Brazil’s capitol, citing the country’s rough history with maintaining its democracy.

The attack occurred following former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s loss in last year’s run-off election against Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, when many claims came from Bolsonaro and supporters of a stolen election.

After Brazil’s electoral court certified Lula’s victory following an intense military investigation, Bolsonaro refused to accept defeat and decided to remain hidden from public view, only going out to urge his right-wing supporters to halt roadblock protests over his loss, The National News said.

Maranhão said that the “terrorists” responsible for the failed coup on Jan. 8 in Brazil were very inspired by the Jan. 6 United States Capitol attack exactly two years prior, when former President Trump’s efforts to annul the 2020 elections came to a catastrophic stunt when his followers stormed the U.S. Capitol after his defeat.

However, this year’s attack on Brazil’s federal government buildings were not only physical attacks, but Maranhão said they were also philosophical attacks. The impact the attacks had on the Capitols in the United States and Brazil, he said, was the main distinction between the two.

“They not only attacked our capitol, the Congress, but they also attacked the palace of the presidency, our executive power, and the Supreme Court building,” Maranhão said. “So it was inspired by what happened in the capital here, but the dimension of that in Brazil was even bigger.”

Graphic design freshman Matheus Portela said that even though his family was safe and distant from the attack’s center, he nevertheless felt compelled to focus more on potential changes in the economy and policy in wake of this attack on Brazil’s democracy.

“I came to the United States to try and take this world of knowledge to my country, which is what we can see: people fighting for politicians who really cannot change their lives,” Portela said.

Maranhão said that Brazil’s democracy has always been very fragile due to the challenges it has encountered since its independence in 1822 as a result of the country’s more authoritarian society.

“Many people don’t realize it, but when we talk about Latin America, in general, people used to say, ‘Brazil is the largest democracy in Latin America,’ which is not completely wrong,” Maranhão said. “But the thing is, it is the largest democracy in Latin America only because of the size of the country and its population.”

When looking at the history, Maranhão said that Brazil has had more periods of authoritarian regimes than periods of democracy. Brazil remained a monarchy after gaining independence in 1822, while others in Latin America became republics.

Not until 1889 did Brazil become a republic, and since then, there have been many military coups on Brazil’s democracy, reverting the country back to a dictatorship on multiple occasions.

According to Maranhão, the reason that this coup was a failed one, was because of the historical context.

“Of course, we are not at the cold war anymore, and it made a huge difference, because the military now had no courage to show their faces to the public as they did in the 1960s,” Maranhão said.

He added that because the U.S. recognized the election as a free and orderly democratic election, and Europe did the same after Lula was elected, the Brazilian military and the terrorists did not have the support of foreign nations to attempt a coup.

Maranhão said another reason as to why the attack failed was because of social media.

“Now more people, average people, were mobilized by these kinds of fake news speech, misinformation, and hate speech as well,” he said. “This context also made more average people to be there and show their faces to the public, and even taking selfies and recording, so they were arrested.”

Maranhão said that hopefully Brazil’s government continues to treat this attack on the country’s fragile democracy seriously. Following the attacks, Lula vowed to condemn anybody involved in the invasion, including military and security forces, and referred to the occurrence as “acts of vandals and fascists.”

“So when many police and attorneys investigate the people who did the attacks, they are giving their own feedback about the interviews, and they say that it’s incredible how they really believe that they were saving the country,” Maranhão said. “They truly believe that they were doing something patriotic.”

Maranhão said the Portuguese language has two words for patriotism: “patriotismo,” which is the same as “patriotism” in English, and “patriotada,” which he said is a way of indicating it is a “stupid” way of someone displaying loyalty for their nation, as happened during the failed coup.

“You believe that you are saving your nation, your country, but in fact, you are destroying it,” he said. “You are disrupting the society that you believe you are saving.”