EDITORIAL: Don’t be afraid of good trouble

April 22, 2023

Before we begin, we would first like to thank everyone who rallied in support of Kloe Witt and The Maroon. In addition, we are grateful that interim president the Rev. Justin Daffron, S.J. justly intervened to put right the situation.

Loyola punished a student journalist under false pretenses for doing her job as she was taught to. Maroon journalist Kloe Witt informed the community about the arrest of a student on campus.

Instead of praising the journalist for her diligent reporting, Loyola disciplined Witt with an official student conduct hearing in which she was charged with falsification or misuse of university records and unauthorized recording. Witt was found responsible for unauthorized recording in the public lobby of the Loyola University Police Department.

Witt appealed the responsible verdict on a number of grounds, including the fact that Student Conduct was arbitrating the case while one of their hearing officers was simultaneously testifying against her. The Department of Student Conduct refused to let Witt see the evidence against her in advance of the hearing — something they said is standard practice in their hearings. They never let her see the original complaint against her. And they never let her face her accuser — University Police. In fact, she didn’t even know it was University Police who were accusing her until after her appeal had been denied.

The appeal was denied through an illegitimate review in which the director of Residential Life, Chris Rice, arbitrated the appeal process rather than the proper University Board of Appeals – a balanced panel of faculty, staff, and students meant to act as an oversight to pending appeals that is prescribed in both the Faculty Handbook and the Student Code of Conduct.

The Student Code of Conduct outlines the appeal process and guarantees a student’s appeal will be heard by The University Board of Appeals, made up of 15 members representing faculty, staff, and students. But Rice unilaterally denied her appeal.

This follows heavy criticism of how Rice has wielded his new authority, having been promoted to the director of Residential Life last year, and underscores a troubling pattern of practice in which he has unfairly punished students for things that appear to personally upset him.

Rice is one of a number of actors that helped enable this bullying of a student journalist.

This situation demands we question how many other times this happens unjustly to students who don’t have legal representation or whose cases don’t face public scrutiny. How often does Loyola manipulate procedure to promote a desired narrative?

Witt’s treatment has revealed how Loyola is capable of using their disciplinary system to intimidate students and strip away their duly-owed rights.

After reporting on Witt’s hearing and appeal, an uproar of condemnation from across the nation ensued. Universities across the country, journalists, attorneys and legal experts, and press freedom advocates condemned Loyola’s administration.

Following a slew of online outcry and NOLA.com’s coverage of the scandal, Loyola’s Interim President, the Rev. Justin Daffron S.J., issued a personal apology to Witt for his inattention and lack of intervention. Daffron concluded that he would dismiss all charges immediately and said that he had not known he was able to intervene in these cases and would have earlier.

However, before Witt’s appeal, Daffron was informed about the case by The Maroon and declined to comment on the situation when asked.

The public scrutiny of Witt’s case gave a rare glimpse into the conduct hearing process when a student is accused of violating the Code of Conduct. And it underscores the serious power imbalance that exists.

It should be seen as a warning to every student: if Loyola has punished a student with a fictitious justification, they will do it again, and have likely done it before.

Loyola charging Witt with unauthorized recording is a perversion of a rule meant to prevent upskirt photos and being photographed in bathroom stalls. The university equated this rule to Witt’s thorough journalistic responsibility to record her interaction with “public safety administrators.” In her hearing, Loyola accused Witt of recording in a private space, but a police station accessible to the public with 24-hour video surveillance does not constitute a reasonable expectation of privacy – especially when knowingly talking to a journalist. To establish a reasonable expectation of privacy, a person must exhibit an actual (subjective) expectation of privacy and the expectation must be one that society is prepared to recognize as reasonable.

It is indicative of a troubling effort to weaponize the disciplinary systems against students, and journalists are only their most recent target. The Department of Student Conduct and Loyola’s arbitration system would rather hold these hearings behind closed doors and intimidate students than have a transparent process.

This case should have fallen beyond the Department of Student Conduct jurisdiction. Why were Residential Life professional staff able to hear these charges through the Department of Student Conduct in a kangaroo court? They should not have the authority to bring charges on their own and should have been obligated to request charges be brought and request a hearing be convened through an independent process. Rice should not have the authority to convoke a disciplinary hearing against a student outside the realm of student life.

We have been taught that no person stands above another and all people deserve dignity. We must uphold these values. We are a respected institution with a long history of admired journalistic practices. We want our administration to represent the values that we have been taught to revere at this Jesuit institution.

We respect Daffron intervening in this injustice.

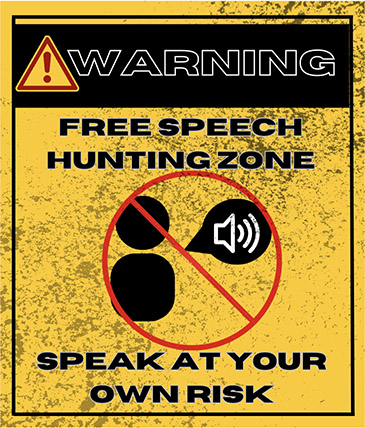

We are all here to learn and grow. No one is above criticism, and as an independent media organization, we seek truth in all things. The freedom we have to discuss this issue with our community is a demonstration of Loyola’s commitment to free speech and independent journalism – but make no mistake, this is at risk.

As a community, we must stand up against administrative authorities cosplaying campus despots and immediately return to some oversight before it’s too late. It makes us all look bad when it may only be a small administrative arm of our university.

And don’t ever fear retaliation for doing what is right. No progress has ever been made by conforming to unjust rules and procedures.

“Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.” – John Lewis