While researching a pillar of Loyola’s social justice past, a writer stumbled on a previously unknown connection between Father Louis J. Twomey and Martin Luther King, Jr. While that is a breathtaking find, it is just the tip of the social justice work this Jesuit priest dedicated his life to.

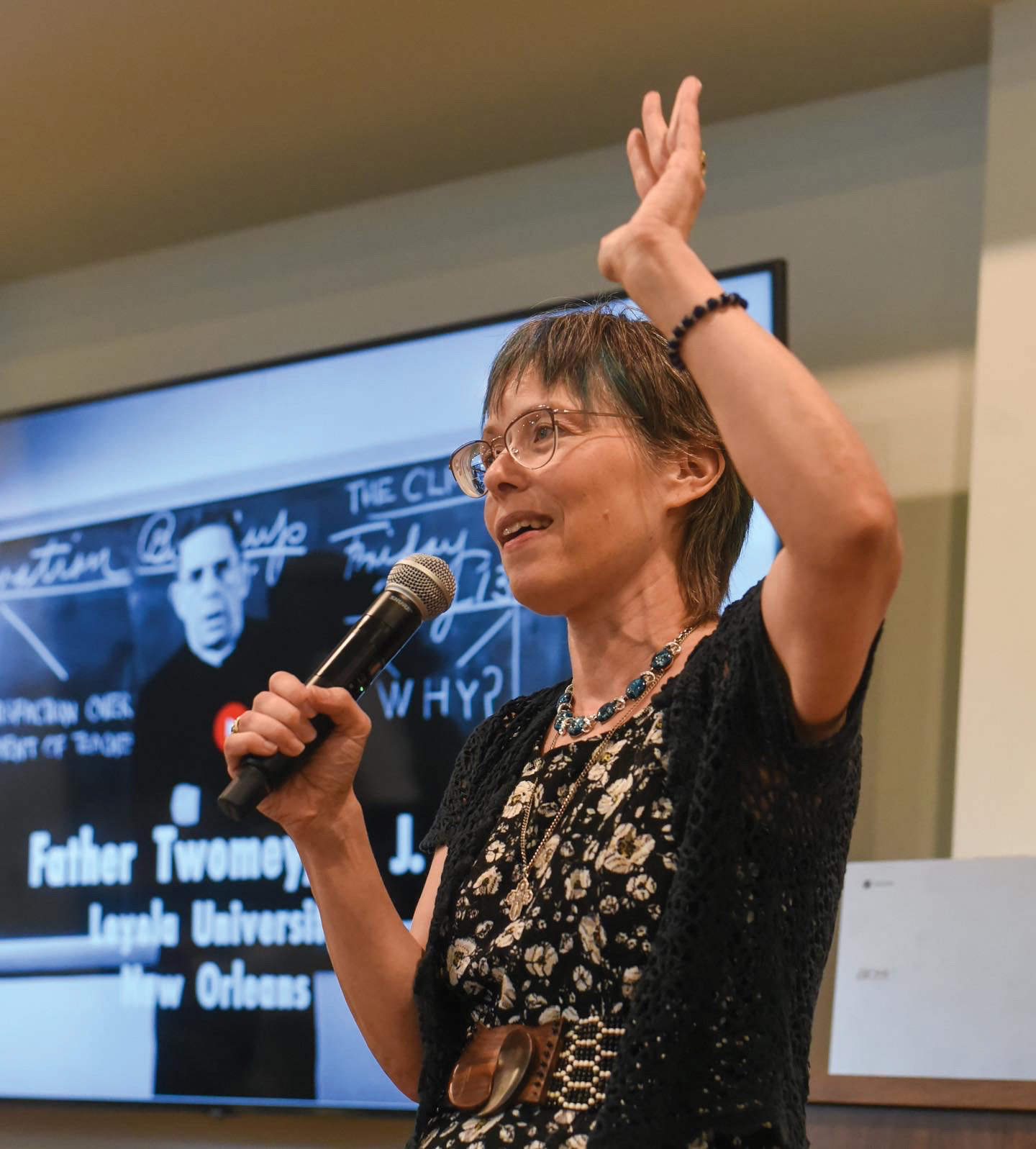

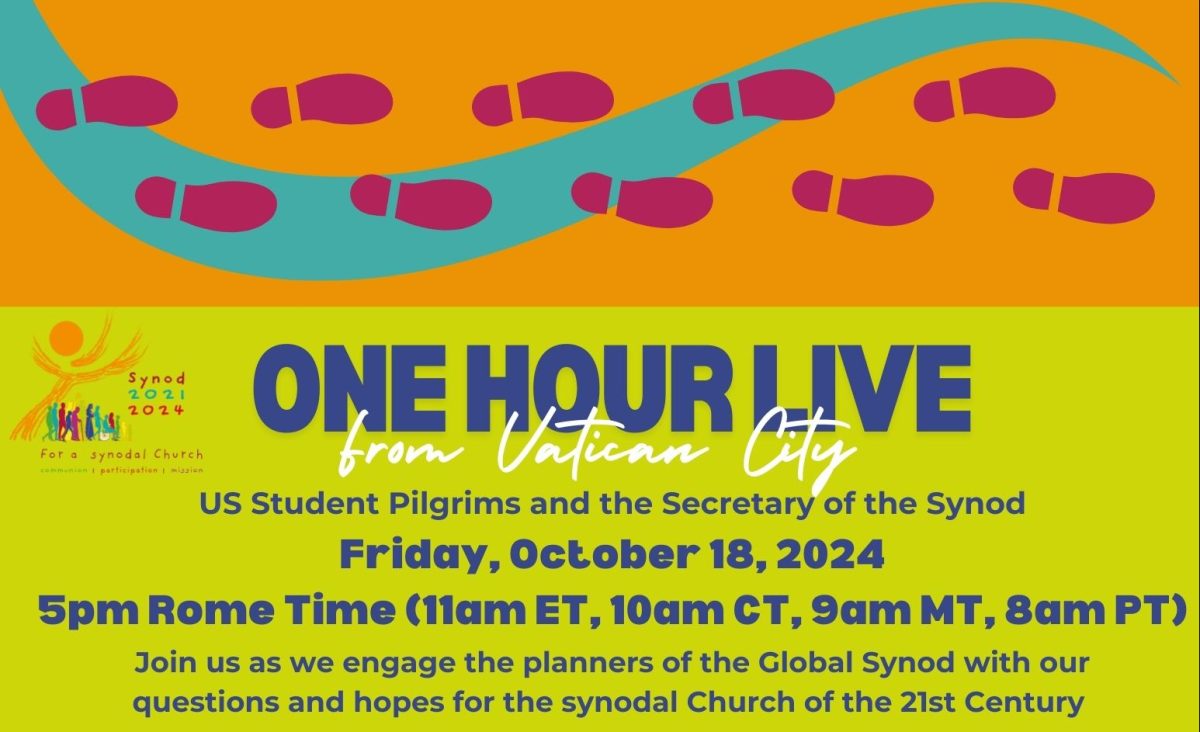

Writer Dawn Eden Goldstein spent over a month researching Twomey’s life and work in social justice for her upcoming biography on the Jesuit priest who called Loyola home for over a decade. In doing so, she uncovered previously unreported letters and correspondence between Twomey and King spanning more than a decade.

Goldstein combed through Loyola’s Special Collections – an archive in Monroe library – finding records of Twomey’s work, with special focus on his commitment to combating racism in the South during the mid-20th century, which was considered a highly controversial and dangerous line of work at the time.

Faith and Social Justice

Goldstein was drawn to researching Twomey since she noticed he broke certain stereotypes commonly attributed to devout Catholic priests at the time, specifically the ideals that one could not be devout to their faith and work for equality.

“There are many people that think that if you’re good, holy, orthodox, and faithful, then you’re not one of those peace and love social justice people,” Goldstein said.

According to Goldstein, it was this combination of faith and social justice work which he lived by.

Goldstein said Twomey believed faith should be the ultimate motivation in people’s lives, especially in regards to social issues including fighting racism and classism.

“He believed that faith should be in everything that we do,” she said. “He [used] all the power of his voice and rhetoric to tell people if you didn’t hear about [racial and social issues] in the church growing up, then the church was wrong not to tell you about this.”

Although he wouldn’t place blame on the church, Goldstein said Twomey did criticize those who didn’t teach of these issues.

“He would criticize those people who were cast with conveying that teaching and who failed to convey it,” Goldstein said.

These teachings and this work were something Goldstein notes Twomey always felt compelled towards.

“His first love – and always his love in terms of evangelism – was evangelizing what does the church teach about working people, what does the church teach about the poor,” Goldstein said.

Goldstein spoke to the Rev. James Carter S.J., the longest serving president in Loyola’s history, about how Twomey differed from other Jesuit priests in the community who worked in social reform, specifically the Rev. Joseph H. Fichter, S.J.

Fitcher focused on social justice theory while Twomey worked in social justice practice.

Carter explained this by saying you would expect to see Twomey in a poor African-American neighborhood, unlike those who would only speak out and study social issues.

Twomey proved this commitment through his action against white supremacist organizations during this time, specifically the then-segregated Knights of Columbus in the 1950s. He would preach to them over the ideals of social justice and why they should shift their ideals.

Goldstein noted these actions were rooted in his criticism that the United States couldn’t preach equality if they continued to segregate and mistreat minorities and the lower class.

“He’s saying that the whole world is going to think that we’re hypocrites if we keep saying we stand for equality and justice when we’re not practicing it at home,” Goldstein said.

Service to Loyola

Twomey joined the Loyola community in 1947 with the idea of starting a labor school, which he successfully accomplished and named The Institute of Industrial Relations.

Since this time, the labor school has closed, although close relations still exist in the Jesuit Social Research Institute, according to Goldstein.

After about a year at Loyola, Twomey created “Blueprint for Christian Reshaping of Society,” a newsletter Goldstein said was to teach “how we can be better” as Jesuits.

Twomey wrote that this newsletter was intended “to create a society in which the dignity of the human person, in whomsoever found, shall be acknowledged, respected, and protected.”

In one issue of these newsletters, published on Jan. 15, 1949, Twomey wrote of the approach of combining the progressive ideas of the emerging civil rights era with the basic tenets of Christ’s teachings.

”The extent to which we, in operation with other soundly progressive agencies, are able to impregnate these economic and social changes with the principles of Christ will be the measure of the Christian character of the new South,” Twomey wrote.

In his continued crusade against racial discrimination, Twomey began teaching racially integrated classes in 1950, before segregation was outlawed by the Supreme Court.

Goldstein credits this initiative to Twomey’s strong conviction that what defines people was their character and their virtues.

“[Twomey] cares only about our virtues in Christ, justice and peace, and charity. And imagine this powerful person on your team- [he] has your back,”

Correspondence with Martin Luther King, Jr.

Goldstein discovered 10 years of Twomey’s letters and correspondence that she claims to have been stolen from Loyola’s archives by a faculty member who served during Twomey’s tenure at the university.

Although he refused to return the original letters, the former faculty member provided typed copies to the archives, which Goldstein used to further her research.

These documents included letters and correspondence between Twomey and other social justice leaders, most notably the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr..

According to Goldstein, Twomey and King had been in contact since April of 1954, before King received his doctorate.

“Father Twomey met him very early and really became, certainly his first Catholic ally and I’ll say, very likely his first white ally in the field of race relation,” Goldstein said.

Twomey would continue to send letters that would help King gain support within the Catholic community.

Many years later, King would continue to refer to his friend Twomey in letters to other Loyola community members, including the previously mentioned faculty member who had possession of the original correspondences. King would check in with Twomey’s acquaintances to hear how he was and wish him well, which Goldstein noted proved a great friendship.

“There’s clearly a great love, intimacy, friendship between these two,” Goldstein said.

His Legacy

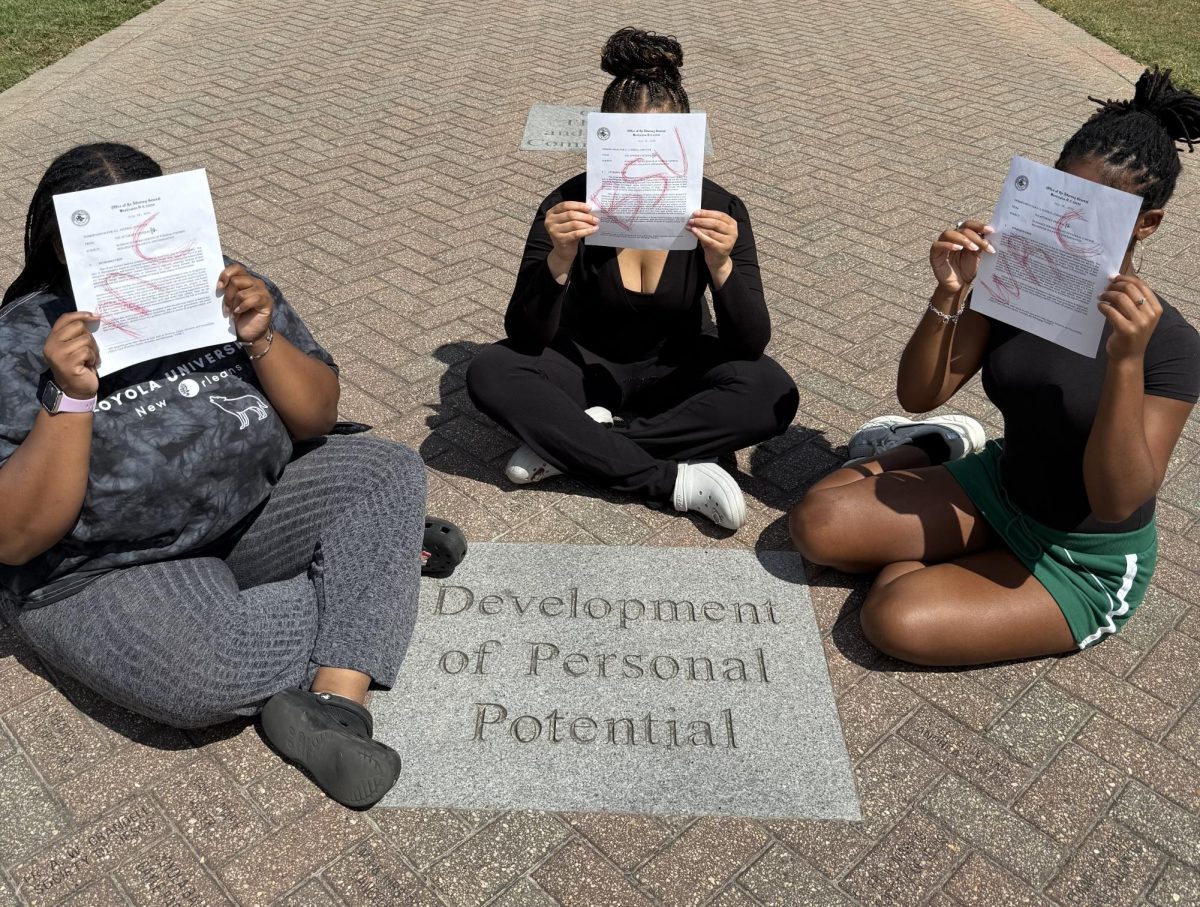

Twomey’s impact continues to shine bright in the Loyola community. For instance, the Twomey Legacy Scholar in Residence award, issued by JSRI, invites one retired scholar back to the program for a year to write and reflect on their achievements.

The Louis J. Twomey Lounge, the center of operations of the Catholic Studies department, is named in his honor.

And the New Orleans City Street Renaming Commission recommended renaming the street that parallels Loyola – Calhoun – after Twomey.

Goldstein said that Twomey’s courageous devotion to an equitable society inspired her to write this biography.

“It’s that kind of courage that makes me feel that the world needs to hear about Father Twomey and about his witness,” Goldstein said.

In the publication “The Catholic World,” in the December 1938 issue, Twomey affirmed the basis of his Christian and moral philosophy.

”Of the gigantic social problems which demand solutions in the world today, there is none more critical than that existing in the lower reaches of society,” Twomey wrote.

David J. Cortes • Nov 3, 2023 at 6:56 am

The article says: “Goldstein was drawn to researching Twomey since she noticed he broke certain stereotypes commonly attributed to devout Catholic priests at the time, specifically the ideals that one could not be devout to their faith and work for equality.” If this is true, then Goldstein knew an appalling nothing of the many activists for equality among the Catholic priesthood during the ’60s. Fr. Twomey was one of them. Goldstein must not know, either, that even the music of the time remarked on Catholic priests’ activism:

“And when the radical priest

Come to get me released

We was all on the cover of Newsweek.”

This lyric, from the Simon and Garfunkel song “Me and Julio,” was a reference to the Jesuit Daniel Berrigan, who, in all probability, knew Fr. Twomey.