Few places Bobby Bissant has officiated in hate men in zebra stripes like the Montaigne Center at Lamar University.

Bissant was a mercurial scorer and speedy ball-handler for the Wolfpack from 1969-71. Ironically, today he sanctions similarly described guards for dribbling violations and charging fouls as a referee in the Big XII, Conference USA, Gulf Coast Athletic Conference and the Southland Conference, where Lamar plays.

“Every time I blow my whistle, half the arena’s going to love me and half of it’s going to hate me,” said Bissant, whose 21.6 points per game at Loyola still stands as a record for the best individual scoring average. “But I just love being around the game.”

“Those stands keep you on your toes,” Bissant said. “They want every call to go Lamar’s way regardless.

“From the moment the crew gets there, both campus security and the town’s sheriff walks us from the parking lot to the locker room,” Bissant said.

That’s because, according to Bissant, fans unhappy with the calls their team was dealt stormed the court, past security, and assailed the referees for retribution a few years ago. “It was bad,” he said.

But even in the more subdued venues, alums, students and cheerleaders let Bissant have it – whether it be a deafening storm of boos or a singular insult (that his garb would better serve sizing Foot Locker’s clientele then collegiate athletics, for example).

It’s enough to keep most people away from the profession. But for Bissant, that’s little more than a hassle – it takes infinitely more to unsettle a man who came face-to-face with the hideous horns of bigotry, isolated thousands of miles away in a French communist sector during the Cold War.

AN OFFER HE REFUSED

The 2005 Disney flick “Glory Road” ended with collegiate tyrant Adolph Rupp and the all-white University of Kentucky Wildcats succumbing to seven black Texas-Western basketball players in the 1966 national championship. It documented the first time an all-black starting lineup won college basketball’s maximum prize in the face of relentless bigotry and Rupp’s disrespect.

Had the movie documented the following off-season, viewers would have seen Rupp telephoning Bobby Bissant, then a senior at Xavier Prep, at home and offering him a scholarship to play ball for Kentucky, then a four-time national champion starring All-American Pat Riley, now the coach of the NBA champion Miami Heat.

That the “Baron of the Bluegrass” singled Bissant out for a scholarship was, in a word, flattering. He’d played some of his best ball at Loyola’s Field House in a Catholic Youth Organization tournament and drawn attention from scouts because of his ability to score by the bucketful and his smart ball-handling. But in his wildest dreams, Bissant never suspected the Baron himself sought his services.

“I did my homework and then realized that I’d be the first African-American recruit ever to sign there,” Bissant said. “I’d put it together. Kentucky had lost to Texas-Western and now he was simply hunting for players.” Black players he’d unleash on the black players that beat him.

Unwilling to play for an infamous bigot, Bissant phoned Rupp back and respectfully declined.

“I still remember his gravelly voice,” Bissant whispered with a disbelieving chuckle.

Regardless, Bissant wanted to get out of New Orleans for college and signed with the University of Albuquerque for two years before they folded their athletics program. He found himself armed with a dangerous skill set but no squad in 1968.

That’s when both his father and Loyola Hall of Fame baseball coach Louis “Rags” Scheurmann “railroaded” the 6-foot-3 guard into a spot on Loyola’s basketball team and a room in Biever Hall.

The Maroon lauded Bissant’s transfer in the Nov. 7, 1969, issue: “The find may be (head coach Bob) Luksta’s biggest since his arrival at Loyola.”

His presence made an immediate impact. Bissant plugged the University of Tampa for 26 points and hauled down an eye-popping 15 rebounds in his debut with the Wolfpack that December, a 91-86 win.

“He has all the speed and ball-handling qualities to do a fine job for the ‘Pack,” The Maroon read.

Six-foot-11 Wolpack center Tyronne Marionneaux, who was eight inches taller than Bissant and held Loyola’s all-time scoring record until Brian Lumar broke it in 1995, said he looked up to him. “Even though I have all the records, I considered him a better player. In my mind, he was the man.”

Bissant had to summon his powers to be “the man” – and then some – when he crossed paths with Baton Rouge’s grand magician of the basketball court: a guard on the LSU Tigers they reverently called “Pistol.

WAR WITH A WIZARD

Bissant knew two things concerning his bout with Pete Maravich, one of two players to win the NCAA’s scoring title three years in a row: that it would go down in a place that “smelled” and that he’d wage war with a floor general who could seemingly conjure black magic from another world.

“Anytime you defended him well and you were about to block his shot, he’d have this pass that he’d put in between his legs. Or around his back. Or behind his head,” Bissant remembered. “And he’d come down the court and call all the plays – they were all screens for him to run around and shoot. He had these two huge forwards and you couldn’t move them – you’d just run right into them.”

For their 1969 showdown with the Tigers (held in LSU’s John M. Park Coliseum, an agricultural center that housed sheep and horses for the rodeo ring below the raised basketball floor), the Wolfpack devised what Bissant called a “perfect gameplan” to double-team Maravich, who the previous year had railroaded Loyola for 52 points and had embarrassed them with a 40-foot behind-the-back pass for one of his 11 assists at Loyola’s old Field House.

Either Bissant or teammate Step Johnson would spin off the immovable picks while the other bore down on a dribbling Maravich to slow him down. Then they’d both abruptly meet at Maravich and trap him, hopefully forcing him to try an ill-advised pass or disrupt his dribble and cause him to expose the ball for a steal.

“But he was too quick,” Bisant said. “By the time one of us spun off, he was a step behind us, through the lane and shooting a jumper.

“And they were all bottom (of the net),” he lamented.

Loyola dropped the decision 100-87, surrendering 45 points from Maravich on 18-of-36 shooting in front of an audience of 8,524 Tiger faithful.

But Bissant, who was Maravich’s mark on the defensive end, dealt the dynamo all he could handle and amassed 32 points of his own. “It was work on one end and work on the other,” Bissant remembered. “I was dead tired afterward. ‘Pistol’ was the best I ever played against.”

It seemed that’d be the last Bissant saw of Maravich, who would go on to become one of the NBA’s 50 greatest players ever, engineering memorable performances for the New Orleans Jazz like torching the New York Knicks for 68 points at the Superdome. It would have been 79 had there been a three-point line.

Bissant, on the other hand, collected the highest career scoring average ever at Loyola, leading the Wolfpack to a 16-11 record in 1970-71 before being drafted by both the NBA’s Chicago Bulls and the ABA’s Indiana Pacers.

“I was there for little more than a cup of coffee,” joked Bissant, a late-round pick who didn’t catch on with either squad. His crowning pro achievement in the U.S. unfolded while working out for the Buffalo Braves, when Bissant once poured in 62 points for a minor league team in Hazelton, Penn.

Afterward, he chased opportunity overseas and, one horrific day, booked a bus ride into hell.

‘I WAS SCARED FOR MY LIFE’

As the hatred swirled in the atmosphere around him, Bobby Bissant – standing a world apart in the hostile confines of an arena in the French communist sector Ste. Marie-aux-Chene – realized he’d ventured quite a ways.

He’d just come off spending one brilliant year with a Dutch “Eredivisie league” squad based in Amsterdam, named the Mars Energy Stars (they were sponsored by the candy company). There he battled former teammate Tyronne Marionneaux six times an ocean away from the St. Charles Avenue campus.

Marionneaux, who played for a ball club sponsored by Levi’s Jeans in the Dutch city of Haarlem, led his team to victory over Bissant’s four times. “It was war” on the court, Bissant remembers, and they led different lifestyles off the court, but knowing someone comforted them both.

“He was a ladies’ man,” Marionneaux said. “Very hip. I was the shy guy.” But they kept each other company and helped each other adjust in the strange European neighborhoods they found their lives unfolding in. While Marionneaux continues to reside and make his living off basketball in the Netherlands, Bissant split ways after a short while.

Bissant’s one-year stint in Amsterdam, highlighted by his copious scoring and deft ball-handling, drew attention from a club based in Strasbourg, France. The Amsterdam club cashed in on their guard, selling his rights to Strasbourg.

Now, with Belgium’s borders separating Bissant from his successes with the Mars Energy Stars, a volatile mob in Ste. Marie-aux-Chene showered him with vitriolic chants and gestures from the moment he stepped off the bus as they tried to approach him.

“It’s like they were mindless peasants that were brainwashed,” Bissant said. “I don’t think they’d ever seen a black person in their life.”

After absorbing their abuse through pre-game warm ups, Bissant had enough. In what he called “broken Louisiana French,” he approached a teammate and asked him what they were saying.

“I don’t want to tell you,” his teammate responded.

“They’ve been at me since we been here, and only me,” Bissant barked. “Now I want to know what it is they’re saying, so tell me.”

His teammate paused, and with utmost reluctance, proceeded to tell Bissant what the crowd was verbally flinging at him. “They’re calling you a gorilla. Saying that you’re a monkey. That you’re nothing but a black dog.”

An electric shock shorted within Bissant’s limbs, and he realized he was fearful. “For the first time ever, I was honestly scared for my life,” continued Bissant.

But he bottled up his fear and safeguarded it somewhere far away from the floor. Using weapons he knew would hurt Ste. Marie-aux-Chene’s boosters where it counted – on the scoreboard – steel-willed Bobby Bissant powered Strasbourg to a win in the toughest atmosphere he’s ever been submerged in.

“It was a hassle to leave,” Bissant remembered. “We had to be taken out by police escort to this plane the owner of our team had to get to fly us back out to Strasbourg.” The mob of people, lusting to lynch that pesky black guard that had just dealt them a loss, cut off the exits and trapped the visitors in their locker rooms.

Three decades later, in the comfort of New Orleans, Bissant chuckles. An experience like that, he confesses in jest, facilitates blowing the whistle on a close play while officiating at Lamar University. “It’s nothing. Nothing.”

SERENDIPITY

Sitting in TJ Ribs, a sports bar in Baton Rouge housing an extensive collection of LSU memorabilia, Bobby Bissant looked over his right shoulder, tapped a tabletop, and said, “We were sitting right here.”

In the summers, to stay in shape and keep his observations sharp, Bissant officiates high school AAU games all over the state of Louisiana.

Riding back from a tune-up game in Lafayette seven years ago, members of Bissant’s crew hungered to grab lunch at TJ Ribs.

They got out the car and, while part of the crew sat at the table, Bissant and another ref made their way to the bathroom to wash their hands, past a glass and oak chamber housing LSU legend Billy Cannon’s 1959 Heisman trophy on a spinning platform.

Bissant’s companion remarked seemingly to no one, “I wonder if they got any pictures of ‘Pistol’ here.”

As serendipity would have it, TJ Ribs did – a shrine just to the left of the restroom entrance devoted to Maravich’s finest acrobatics. They stopped and gazed at a picture of Maravich suspended in mid-air, brandishing an impeccable shooting form, two defenders jumping with him and shoving their hands in his face.

Just as Bissant was about to muse about the time he went at it with the LSU magician, his eyes made out the number, jersey and face of one of the framed defenders.

The number was 30. The road jersey was Loyola’s. And the face was his.

“Holy smokes,” he said to no one. “That’s me.” And Step Johnson.

“Hey, look, Bobby!” blurted his companion. “Wow. It does look like you.”

Bissant was overcome for an instant by the feelings of wonder he had while bearing down on Maravich that night. There’s no way Maravich could have seen the goal and no way he should have made that shot pictured in the frame.

Maravich swished it, of course, in both Bissant and Johnson’s eyes.

The moment passed, and then Bissant was overcome by something else – courage, a sense of relief, of accomplishment, that nothing had barred him from taking the court and participating in the game that had been his life in the manner he wanted.

Not overzealous fans who waywardly lust to harm referees.

Not bigots in the bluegrass with a hard-to-resist offer.

Not bigots in a communist sector halfway across the world with a penchant to kill him.

Not staring down the barrel of a ‘Pistol.’

Not anything.

Michael Nissman contributed to this report. Ramon Antonio Vargas can be reached at [email protected].

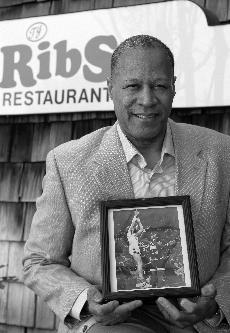

Former ‘Pack guard Bobby Bissant, now a college-level referee, scores a ginger-roll in traffic at the Loyola field House in 1969.

Brenda Stewart wilson • Apr 4, 2021 at 5:01 pm

Old friend! Brenda Stewart Wilson Baton Rouge La

roel Tuinstra • Jan 1, 2021 at 1:16 pm

I was a former teammate from Bobby Bissant in Zandvoort .can anybody vive me vis emailadres or telephonenumber?

Roel Tuinstra

Amsterdam

Holland