Loyola University has begun a review of its liberal education curriculum (the “Common Curriculum”). Liberal education makes an irreplaceable contribution to the university’s goal of educating students as whole persons. Liberal education definitely needs to be reviewed, renewed and above all strengthened. According to planning documents, “the Jesuit tradition of liberal education” must play a defining role in this renewal.

As a Jesuit for 46 years, a teacher at Loyola for 24 years and as a founding faculty member of a college designed to provide the finest liberal education in the Jesuit tradition to African Jesuit seminarians, I know the tradition. But I am in fear and trembling as we begin to review liberal education at Loyola. Why? Let me explain. As part of my research for a doctoral dissertation on the reform of university education, I studied the history of liberal education in the United States.

The story line is clear: Beginning in the late 19th century and continuing through the 20th century, the research university model dominated. As the professions and academic disciplines developed, the teaching credential for higher education became the doctoral degree in one of these specialized disciplines. College teachers came to understand themselves first as chemists, historians, psychologists, philosophers, and were rewarded for refereed research in their specialty or sub-specialty. Loyola faculty, myself included, is no different, nor would I expect them to be.

But how strong was the liberal education of our current faculty? How many have studied philosophy and theology, the heart and soul of the content of liberal education in the Jesuit tradition? I fear lest “the Jesuit tradition” be taken as a blank slate on which faculty write what’s in the interest of their discipline, their major, their profession. I fear our reform will further shrink the size of the Common Curriculum, cut philosophy and religions studies requirements (as has happened at some of our sister American Jesuit universities).

I challenge my fellow faculty and interested administrators and students to study the Jesuit tradition of liberal education. Among the founding documents are Part IV of the “Constitutions of the Society of Jesus, the Ratio Sudiorum” of 1599, recently translated into English by the Rev. Claude Pavur, S.J., of St Louis University. Also illuminating for how the Jesuit tradition of liberal education might be renewed would be the documents of the recent Jesuit General Congregations and the post-Vatican II revision of programs of studies for Jesuit students. Histories of individual U.S. Jesuit colleges and universities reveal how Jesuit liberal education was inculturated in the U.S. social and educational environments.

My own reading of the Jesuit educational tradition provides no reasons for complacency about the Common Curriculum. For example, a major defect of the philosophy three-course requirement lies in the lack of sequence for the second and third courses. The Jesuit educational tradition stresses mastery of materials in an orderly sequence of graded difficulty. Juniors and senior should be expected to build on what they learned in introductory and second-level courses. They should be taking courses that increasingly challenge them as they progress from freshman to senior years. Longer reading assignments, more complex writing and general higher expectations would be evident as one moves to higher levels. A senior-level Common Curriculum capstone seminar, perhaps interdisciplinary, might be added.

A second major concern (closely related to sequencing) I have about the Common Curriculum focuses on the extent of demands on students. The Jesuit tradition has always insisted students must be actively engaged – taking notes, reviewing, organizing, criticizing, debating – alone and with others. The teacher’s task for students is like the retreat director’s for retreatants: to give them exercises (papers, quizzes, reports, projects, debates) that elicit their own efforts. A renewal of the Common Curriculum in the Jesuit tradition requires eliminating (or radically revising) all so-called “blow-off” courses, courses that make minimal demands on students. More than anything else such courses work counter to a fundamental principle of Jesuit education. I suggest that Common Curriculum courses (as well as all others) should require at the very minimum two hours of varied out-of-class exercises for every hour in class.

What we do by way of liberal education at Loyola can be done better. We can and must do more to foster our own and our students’ liberal learning. One element of the Jesuit tradition inspires the suggestions I have sketched above. Let us together learn about this tradition so we can indeed “strengthen undergraduate education in the (authentic, my addition) Jesuit tradition.”

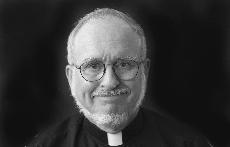

The Rev. Stephen Rowntree, S.J., is chairman of the philosophy department.