KONY 2012. Everyone has an opinion about the video that in two weeks garnered over 100 million views and has sparked a global discussion about activism in Africa. As the video went viral, academics and policymakers launched a multitude of critiques. The nonprofit organization that produced the video, Invisible Children, stands accused of over-simplifying the complex nature of the conflict while simultaneously engaging in a civilizing mission motivated by white guilt.

As both a specialist in sub-Saharan Africa and as someone who works with human rights advocacy organizations, Kony 2012 and what it hopes to accomplish fascinates me. However, much to the frustration of many students, colleagues and friends, I have avoided giving my opinion on the campaign. Until now.

Before continuing, let’s establish a common working knowledge about the video, the campaign and Invisible Children. Invisible Children’s mission is to raise awareness about the Lord’s Resistance Army in central and east Africa. Over the last nine years the organization has developed a two-pronged strategy. First, the organization aims to educate high school and college students about the destructive power of the LRA. Led by Joseph Kony, the LRA has contributed to the destabilization of political, economic and social conditions in Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic and South Sudan. In 2005, the International Criminal Court indicted Kony and three others on crimes against humanity and war crimes. In addition to its educational platform, Invisible Children establishes durable programs to rebuild and to help Ugandans protect themselves from future attack.

Kony 2012 proposes that if we make Kony as famous as any celebrity, he will no longer be able to evade arrest and trial. We are asked to step outside of ourselves, to redefine the propaganda machine and to take Banksy-style action. The campaign also encourages us to pressure Congress to maintain funding for the 100 U.S. military advisers charged with the task of providing technological support to the Ugandan army as they track Kony.

With a common foundation established, what is my opinion? The campaign is imperfect and incomplete. Will young people be able to successfully pressure the culture and policy makers into making Kony a priority? Will pushing “like” on Facebook have a measurable impact? I don’t know. A campaign of this magnitude has never been attempted before – certainly not one that deploys the vast and ever expanding array of social media. Additionally, responding to grave human rights violations with military pressure has proven time and time again to be ineffective and potentially damaging to local populations. I fear that 2012 will come to a close with Kony still at large.

However, this personal skepticism is not a condemnation of the campaign. I do not share the opinion held by many academics angered by the glossy nature of the video. Some have suggested that Kony 2012 encourages a blind activism devoid of academic rigor and is an active participant in a civilizing mission that marks Africans as nameless victims incapable of helping themselves.

My interpretation of the campaign is more optimistic. I read Kony 2012 as a call for each of us to educate ourselves about the conflict’s history and to reflect upon what advocacy means. For those of us who stand before you as professors, it serves as a wake-up call. As educators, we must actively engage the issues that concern you; we must utilize our expertise in ways that facilitate debate. If I feel that Kony 2012 fails to nuance the historical narrative of the LRA, then it is my job to provide that nuanced narrative so that students can develop an informed opinion.

Kony 2012 is accomplishing something truly amazing: it is putting the LRA, Africa and the contested world of development and human rights on the table as a critical set of issues to be discussed and debated. We live in a society in which Africa is described as a country rather than a continent of fifty-five nations. Kony 2012 attempts to humanize a place, a people and a conflict that many of us have never heard of before. The campaign asks us not only to care but to educate ourselves about what has happened, is happening and, perhaps most importantly, what could happen if enough people committed themselves to both education and activism.

The campaign is imperfect, but it is important. If you haven’t watched Kony 2012, watch it. If you have watched it, ask questions. Meaningful and durable change is maddeningly slow, but if this campaign compels enough of us to question, reflect and search, then perhaps we are indeed witnessing the death of apathy.

Kathering Fidler is an assistant professor for the history department. She can be reached at kgfidler@loyno.edu

On the Record is a weekly column open to any member of Loyola’s faculty and staff. Those interested in contributing can contact letter@loyno.edu

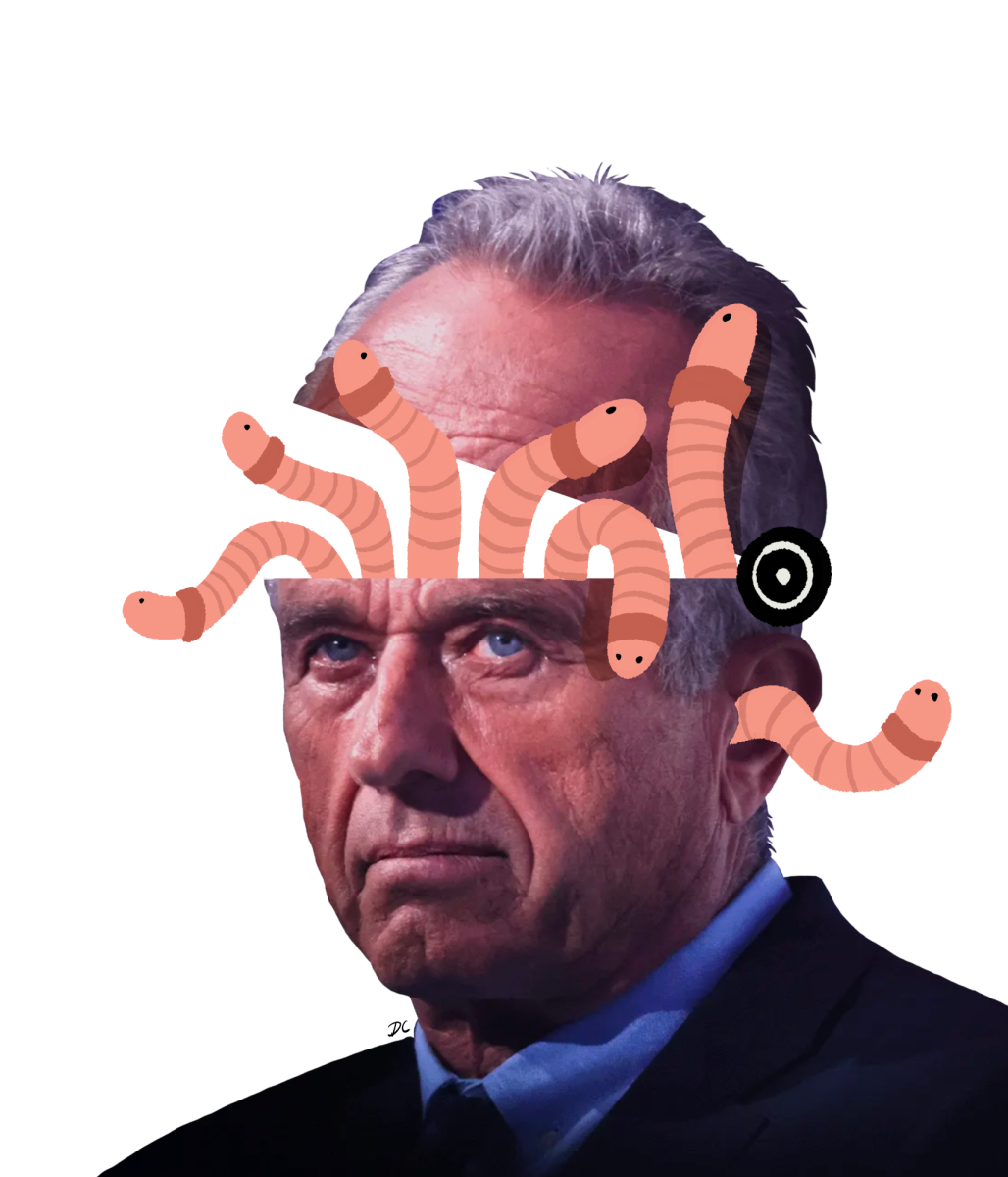

Invisible Children uses social media to make child abductor Joseph Kony “famous.” (KONY2012.COM)