After an eight hour flight to Germany, sitting next to a man on whom I accidentally sneezed and after taking a train I wasn’t even sure was correct from the Düsseldorf airport to the Hauptbahnhof (main station) of the city in which I would be studying, I stood at track seven with my 50 pound suitcase and cumbersome backpack.

It was 35 degrees Fahrenheit and cloudy. Though it was noon in Dortmund, I had been displaced from my regular time zone so it might as well have been 6 a.m. since my traveling began the evening before in the U.S. As soon as my train arrived, I scrambled down through the crowds into the station to phone my university contact, using the change I got from breaking a 20 Euro bill with the purchase of Tic Tacs.

The track sign read that the S1 had been canceled, though at the time, I couldn’t understand it or the man on the loudspeaker explaining. But then I met the angel of sorts that my mother promised I’d meet on the way, who informed me of the delay through his broken English. Someone threw themselves in front of the train, he told me.

“What? … Like, as in … Oh … God …”

A tragedy, but an inconvenience mostly, on this day when I felt I’d never make it to a bed.

My helper was also a student at the same school, so, once a back-up plan was announced for the S1, he led me through a route of buses and trains that I would never have been able to maneuver alone. After he showed me another pay phone at the university, he walked away and said, “Welcome to Germany.”

Stranger still than my initial unfamiliar and, at times, terrifying, days in Germany is how familiar and at times comforting it became in just a matter of days. Every time I take the stairs down into the Hauptbahnhof, the smell of waffles and crepes overwhelms the air. Now, it is a scent that I know, one unique in my experience to this specific place of my train station.

When the H-Bahn (the “hanging railway”) is closed on the weekends, my 20-minute walk from my dorm to the main campus is more readily visualized than any daily walk I used to take back home. And though the cashiers at Lidl, a discount grocery store in my neighborhood, don’t help customers bag their items and will yell at you if you take too long to bag, Lidl is nonetheless my grocery store now. I know where things are. I recognize the face of the impatient checkout woman.

After a month and a half studying abroad in Germany, I am struck by how a sense of home is capable of great elasticity, how something so different like a new country can become familiar. Adaptation is a magical thing because it just kind of happens like homeostasis. I never would have thought that there would be a city in Germany that would have a place for me or I a place for it in what I think of as home.

You never know new places where you could belong if you never leave one where you already do.

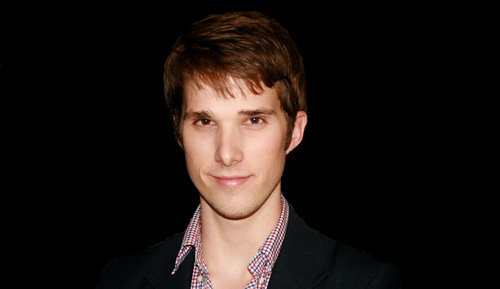

Jonas Griffin can be reached at [email protected]