Having parents mistaking their child’s teacher as a high school student is all too familiar for Zoe Glick, biology A’13.

Glick, along with other recent Loyola alumni joined one of many post-undergrad teaching programs to gain teaching experience, pay off federal loans, or even obtain a debt free master’s degree.

Camilia Santi, A’13, teaches 6th and 7th grade math and 5-8th grade tennis at Arthur Ashe Charter school in Gentilly. Santi didn’t want to leave New Orleans and City Year’s program offered her an excuse to stay.

City Year also placed Matt Harris, A’13, at Samuel J. Green Charter, where he teaches kindergarteners through 4th graders computer lab. Harris said that City Year is an “excellent program” that awards $5,000 towards federal loans or tuition for graduate school.

“It’s a one year commitment in which you’ll receive valuable experience working with students every day and constant coaching and feedback from both your school and City Year staffs,” Harris said.

Harris’ passion for education stems from his mother. He said he’d always wanted to follow in her teaching footsteps.

“I’ve always liked school. I never wanted to leave,” Harris said.

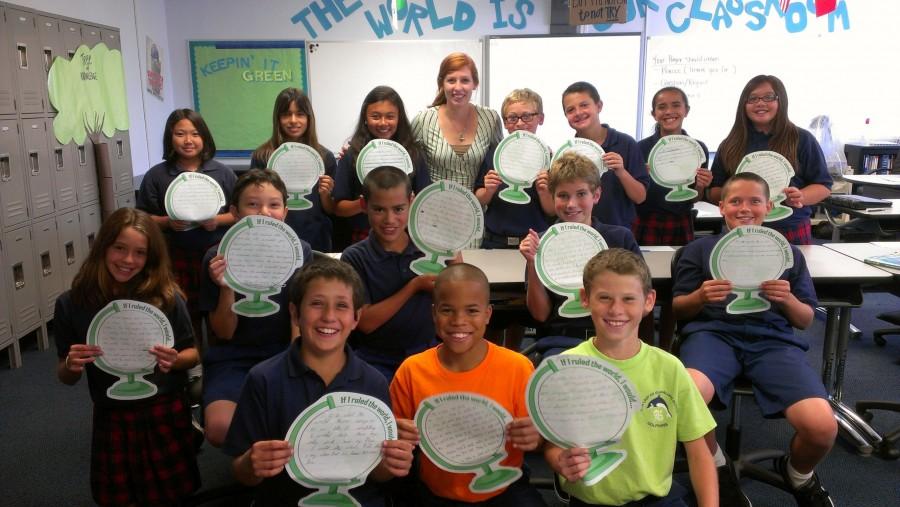

Janece Bell, A’12, teaches 5th and 6th grade math, 7th and 8th grade English and is the 6th grade home room teacher at Our Lady of Guadalupe in Hermosa Beach, California. Through Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles’ Place Core Program, Bell is able to teach while she works on her Master’s Degree, which she will graduate with debt-free.

Bell has always loved teaching and took any opportunity to fulfill her teaching desire at Loyola through volunteering with LUCAP, leading groups in Belize with Ignacio volunteers, tutoring in the ARC, or teaching acting classes.

“I think I’ve always had it in my heart,” Bell said. “Even though Loyola didn’t have an education degree, I was always involved with schools and kids.”

Bell attributes her success to her Loyola education. Her yearlong theatre major taught her to “act like” she knows what she’s doing. Valerie Andrews, assistant professor of mass communication, taught Bell to solve and be upfront with her mistakes through her public relations courses, Bell said. Bell has also written grants gaining resources for her students and admits that it’s primarily due to her writing background.

“I still remember taking professor Martin’s mass comm writing class, and how she completely revolutionized what kind of a writer I was,” Bell said. “I still use the things she taught me to this day.”

Loyola science faculty left a lasting mark on Zoe Glick, who teaches 10-11th grade chemistry at Chalmette High School through the Teach for America program. She says Lynn Vogel Kopliz, chemistry department chair, and C.J. Stephenson, assistant professor of chemistry, opened her eyes to all the amazing things chemistry has to offer while she was at Loyola.

“If I can have even a portion of the impact on my students that my teachers have impacted me, then I think I will consider my teaching career a success,” Glick said.

Glick doesn’t intend on making teaching her career, but she wanted to dabble in teaching before going to medical school. Glick wants prove to students that science can be fun.

“You always hear people complain about their science teacher or hear that science is boring or hard. I want to be somebody who can teach students in a way that’s interesting and relevant to them,” Glick said.

The transition to becoming a full time teacher required “a lot of self-discipline,” according to Harris. He said there is no way he can go out as frequently as he did in college and still perform effectively in the classroom.

“I can spare the occasional weeknight out, but most nights I’m in bed by 9:30,” Harris said.

Sleep is a difficult task for Bell, who finds it difficult to juggle giving students individual attention, finish her grad school homework, do readings and execute presentations throughout the week.

“The job is never done. I can work for hours, I’m just going to stay up all night, I can do that, and I still have 101 things to do the next day,” Bell said.

Although the long teaching hours can becomes strenuous, Harris states that there is never a dull moment at his job.

“You never know what challenges your students are going to bring in through the door,” Harris said.

Bell says that these students impact her life. She explains that last summer she kept waking up feeling “empty.” She couldn’t understand why she was depressed until three days after school ended.

“It hit me that I miss my kids, they were the reason I woke up in the morning, and I didn’t get to see them anymore,” Bell said.

Glick can’t imagine anything harder than teaching, even medical school. However, she says it’s one of the most rewarding jobs she could have chosen.

“Teaching is a huge responsibility. All of a sudden you’re not just responsible for yourself and your own future. You’re responsible for the livelihoods and futures of hundreds of students and that’s a heavy weight to feel,” Glick said.