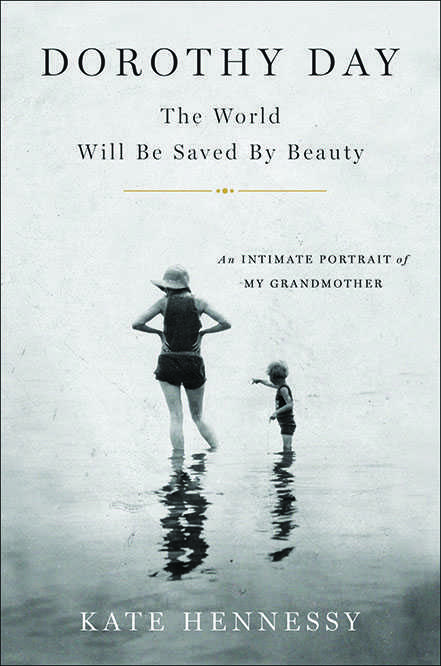

Saint. Anarchist. Activist. Opinions about Dorothy Day vary widely, but a new book by her granddaughter, Kate Hennessy, is shedding some light on the controversial Catholic figure.

Hennessy’s presentation on her book “Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty” drew a sizable crowd to Loyola’s Ignatius Chapel last week, with some attendees sitting in the windowsills and on the piano bench once the seats filled up.

Hennessy read three passages from her book, then took personal questions from the audience that showed Day is still a figure who proves difficult to define.

Audience members asked about Day’s relationship with her husband and the abortion she had in the 1920s, along with how Hennessy’s family feels about Day going through the process of being examined for sainthood in the Catholic church.

Day was a suffragette and bohemian in New York before her conversion to Catholicism in the mid-1920s. She founded the Catholic Worker movement with Peter Maurin, and the two opened and operated communal houses and farms focused on aiding the poor and taking nonviolent political action.

She was arrested several times while practicing civil disobedience, and she edited the Catholic Worker newspaper, in which she advocated the Catholic economic policy of distributism, which she believed fell somewhere between socialism and communism. This led to her being considered a political radical.

When Pope Francis visited the United States in 2015, he included her in a list of exemplary Americans, along with Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr. and Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk and author.

Hennessy said she hoped her book would show that her grandmother was a complex person.

“What has happened is people cherry-pick a certain moment in time in her life and take it as, you know, rock solid, she never changed her mind, whatever. And that’s not true,” Hennessy told The Maroon. “I really wanted to bring her story back down to earth.”

Hennessy focused the story heavily on the relationship between her mother, Tamar Hennessy, and her grandmother. Tamar was Day’s only child, and she was not in as much of a spotlight as her outspoken mother.

“This celebrity business, this ‘celebritization,’ it takes people out of their day to day life, which, what is that? Human interaction. Human love. I really wanted to bring [Day] back into that, and in a way that’s true to the complexity of the relationships between her and my mother and to me,” Hennessy said. “I really wanted to tell my mother’s story. If I didn’t tell it, it would be forever lost, and it’s a huge part of Dorothy Day’s life.”

Hennessy also said she wanted to write about family: both her biological family and the Catholic Worker family, which extends to New Orleans. It’s hard to know just how wide the network is, though, because the Catholic Worker is loosely structured and follows Day’s philosophy of anarchism.

The New Orleans Catholic Worker house is a white and blue double shotgun in the Irish Channel, just a few blocks from the former St. Thomas housing project. It has two large rooms for families who need a place to stay.

The Catholic Workers in the house are Katie Kelso and her husband, John, who re-opened the house after it had been closed for a few months two years ago. It was originally founded in 2010.

Kelso said that the community here focuses on community, spirituality and resistance. They host families in need; serve meals with Hope House, another Catholic charity around the corner from their home; pray together and attend Mass; and work with activist groups Take ‘Em Down NOLA and Fight for 15.

She’s only a few pages into Hennessy’s book but said she’s already encountered a story about Day that she had never heard before.

“I feel like if there’s a woman in the world whose life I want to know about, it’s Dorothy. So I feel like, yeah, I’m connected to her,” Kelso said.

She said that reading books about Day helps her feel close to the Catholic Worker community.

“When you live in community and you live in a Catholic Worker [house], your life is a lot different than, maybe, somebody else’s life. So when you read these stories or you get to talk to other workers, you just both get it, because you’re like, yep, I know what that’s like,” Kelso said, describing the chaos of a Catholic Worker house.

She said that a few days ago, a man from Central Africa appeared on the front porch who spoke only French. He had a slip of paper in his hand with the house’s name and phone number on it.

Kelso also said that whenever the community has tried growing vegetables in milk crates on the driveway, they’ve inevitably been stolen during the night.

It’s these stories, she said, that are common in Catholic Worker communities everywhere.

Hennessey agreed with Kelso. Though she never lived in a Catholic Worker house, she grew up around them and still goes to visit the house Day founded in New York.

“I love the people there, and it’s crazy and it’s chaotic and it’s dirty and whatever, but I just love it. It’s a real sense of belonging there,” Hennessy said.

Hennessy said that even after writing her book, she is still trying to understand her grandmother’s philosophy.

“I can’t get away from it. All these questions, I’m still trying to figure out not only what she meant but what it means to me, and that will be a lifelong process,” Hennessy said.

Dr Michael Camarata • Sep 30, 2017 at 7:14 am

Your gran was an “intentional Christian”, something that creates the very thought of Jesus in each complex action and “choice”.

Given that gift,we intentionally realize that to walk His path is to focus our lives on His Word less we easily slip off The Path on to one strewn with unseen or missed “choices”.