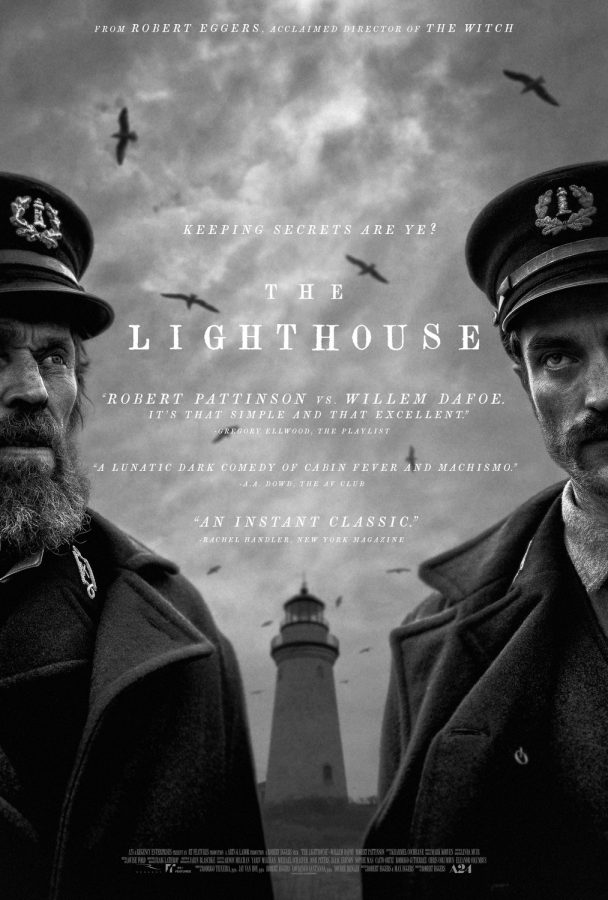

Review: “The Lighthouse” beams toward isolation with manic abandon

January 2, 2020

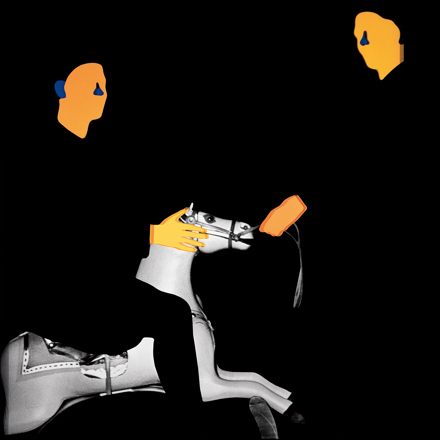

“The Lighthouse” is an engrossing gothic horror tale about the psychological dangers of isolation.

Set in the late 19th century on an isolated island, the tight-lipped Ephraim Winslow, played by Robert Pattinson, comes to work for crusty lighthouse keeper, Thomas Wake, played by Willem Dafoe. Winslow is stuck with serving his annoying boss and companion, as he has no interest in Wake’s attempts at conversation and gradually feels resentment at his monotonous duties on the island. The fragile interplay between the two is tempered by Wake forbidding his servant from going up to the top of the lighthouse, a mysterious chamber which seems to entice the two in entirely different ways. The mounting antagonism of Winslow and Wake eventually gives way to full-on insanity, as they grapple with their terrifying visions brought on by their cabin fever as well as with each other.

Pattinson and Dafoe are sensational in “The Lighthouse”. The former is fun to watch as he painstakingly commits himself to his role, while the latter captivates the audience with his portrayal as a jerk of a boss who drinks, farts and yammers. Winslow and Wake are both masters of their own fate, and they are doomed to abide by it. In a wickedly entertaining way, Pattinson and Dafoe help sell that gloomy experience in what is practically a two-man play.

From its first frame, “The Lighthouse” conveys a gray sense of dread and gloom. Its experimental sensory storytelling is spearheaded by its director Robert Eggers, best known for his equally unsettling horror debut “The Witch.” The film feels authentic with its uniquely black and white cinematography and its 4:3 ratio, which evokes the silent films of the early 20th century. The ever-present cacophony of noise, paired with Mark Korven’s distressing score, further amplify the film’s claustrophobic feel and serve to lock the viewer in with the growing torment of Winslow and Wake.

“The Lighthouse” is more than just a bonafide horror film. Co-written by Eggers and his brother Max, its abundance of ambiguous elements is part of the film’s wicked appeal. Are there really supernatural forces at play? What was it about the mystical beacon of light that serves to daze Winslow and Wake in a trance? Or more accurately, what is going on between the two? While it can be a lot to take in for the uninitiated, the film speaks volumes about its mesmerizing quality, with the intensity of the angry seagull hooting incessantly at Winslow.

While the film is certainly ambitious and maximalist in terms of filmmaking, it doesn’t feel overwhelming. It does not subscribe to the convention of overexplaining that is common with American cinema and, as a result, the audience is treated to a tellingly particular focus on the two main characters as they physically exert themselves in work as well as in play. This plays into the deepening sense of doom for Winslow and Wake as they become riotously drunk and sloppy, giving an impression that the audience is about to watch a nightmare unfold and eventually explode.

But, when it does, it does with nothing more than a resounding whimper. What feels like a juvenile exercise in provocation ends up exhibiting a feeling of guarded consciousness about what it wants to be about. “The Lighthouse,” while certainly arresting, feels like a caricature that threateningly drowns itself in the terror of its own making. While the final act doesn’t necessarily leave a bitter taste in the mouth, it makes the film sound quite eccentric rather than scary.

Nevertheless, that might just be the point. The film revels in the manic self-destruction of the human psyche through the forces of isolation, loneliness, and sexual repression. With his exemplary command of genre conventions, Eggers has tapped into what makes everyone tick, and “The Lighthouse” is a cinematic classic.