Mold displaces Carrollton Hall residents

Myra Hodges walked into their room after Hurricane Ida and was immediately overwhelmed by the musty stench of weeks old mildew and mold. After the smell came the overpowering sights. The floor was soaked, water pooled by the windows, and the walls were bloated.

“Immediately, the smell of mildew hits you straight in the face,” Hodges said. “It was nauseating.”

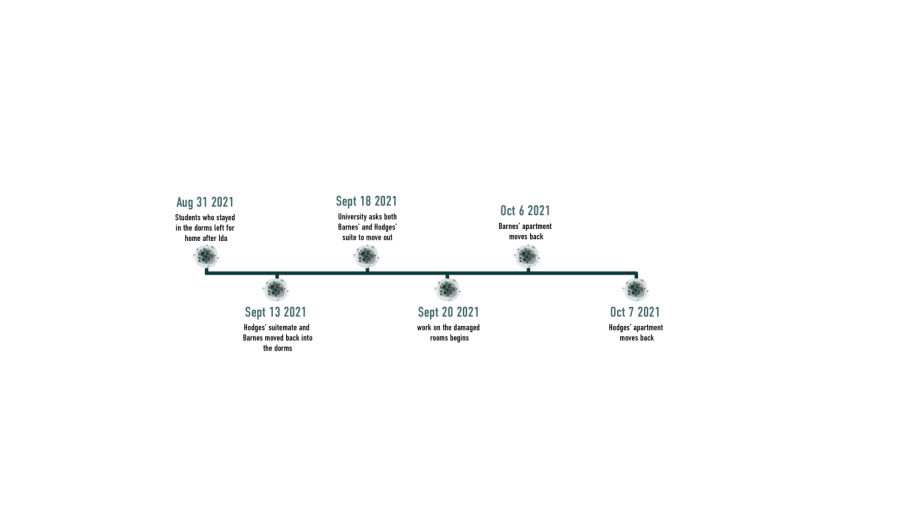

Hodges, a classical studies and sociology junior, returned to campus on Sept. 7 to retrieve some of their belongings and found their suite in this condition. They notified the Office of Residential Life, which told Hodges that they would return to a “clean and pristine” suite that had been shampooed and treated with an enzyme spray.

One of Hodges’ suitemates returned to campus on Sept. 13 after the hurricane to find the room still in a state of disarray. Green, white, and black sludge covered the carpets, walls, ceiling, beds, towels, windows, and cabinets.

Hodges and their suitemates were some of the many students who returned to Loyola after the hurricane to find their dorm rooms infested with mold.

Six suites and apartments on the 6th and 7th floors of Carrollton Hall were affected by mold in some way, according to Chris Rice, director of residential life.

After reporting the mold to residential life, Hodges said they were told to pack enough clothes and supplies for four days and lived off these minimal options from Sept. 19 to when they returned to their dorms on Oct. 6 and 7.

Although some students were originally told they’d be able to return to their rooms on Wednesday, Sept. 22, with the additional time away caused by Hurricane Ida, they were without the comfort of their own beds for over a month.

After the initial mold was dealt with, it became apparent that the problem was deeper than surface mold, causing the students to be displaced for longer than they were originally told. Rice said rain entered through exterior walls and windows during the storm, but that “there is a progressive plan to fully repair the damages” in the dorms.

This is not uncommon in a situation with mold caused by water damage. David Ragsdale, production manager for damage restoration company ServPro Industries, said that mold problems are often bigger than people first suspect.

“Many times, especially after any water-related damages, what you’re seeing a lot of times is just the tip of the iceberg,” he said.

Ragsdale said it’s common for people to deal with the mold they see and then for it to pop back up again later.

To deal with the root of the problem, Rice said the walls in the rooms were removed, treated, and replaced with the supervision of a certified testing company while the students were away. Any moldy carpets were removed and the spaces were treated with enzymes, he said.

The carpet was replaced with wood flooring, the walls were painted, and the windows were sealed, according to Hodges.

Many of the students were moved to temporary housing in Biever and Buddig Halls. Others opted to live off-campus for what they thought would be a short stay that turned into a weeks-long displacement.

Kelly Cernes, psychology sophomore, was offered a room in Buddig but turned the offer down and stayed with a friend because she thought the repairs would only take a few days. After she was displaced for more than a week, she started staying in Airbnbs and with her boyfriend, using his car as a storage room.

“I’m just living out of my boyfriend’s car,” said Kelly Cernes, psychology sophomore. “Because I don’t even have a car.”

Students were not only concerned about the return date to their dorms, they also worried about the money they’d lost living elsewhere.

“I got the call about moving out and immediately ran downstairs to my mom and started sobbing,” Hodges said about losing their money. “I knew I was going to get f——- over.”

Carrollton Hall apartments cost between $4,732 and $5,135 per semester, according to Loyola’s website. However, the Buddig and Biever dorms the students have lived in since being displaced cost nearly $1,000 less, and the students thought they were losing money.

Students displaced by the remediation have since been informed by Rice that they will be given a credit for their time spent elsewhere.

Jenna Barnes, public health sophomore and resident of another suite affected by the mold, said she and her suitemates were given constantly changing and often contradictory information from Residential Life.

Rice said students in these suites were communicated with throughout the process by professional staff members.

Rice said Carrollton Hall doesn’t regularly have mold issues; however, this isn’t the first time mold has been reported in the residential hall. In 2004, Loyola sued various companies involved in the construction of Carrollton Hall over structural problems that resulted in moldy dorms, among other problems, according to a Maroon article.

Hodges said that they felt the university ignored their concerns until it was too late, waiting almost a month after Ida made landfall to move them out.

“If they had just listened to us from the start, we’d be back in our rooms by now,” Hodges said Oct. 4.

Students were allowed to move back into their rooms a few days later on Oct. 6 and 7, Hodges and Barnes said.

As they were dealing with the mold problems, residents said they were nervous to talk to their residential assistant.

Students shared messages in which Shamaria Bell, residential assistant of the 6th floor of Carrollton Hall, told them to stop talking about the mold after the students had been complaining in their floor group chat.

“It’s not productive,” Bell said in the group chat. “Period. It’s done.”

Bell told The Maroon to speak to Chris Rice for a comment.

Hodges said some of the students felt like Bell’s language was dismissive and that they weren’t being listened to.

“(Bell) approached it as if I was being entitled about wanting to live in the room I paid for,” Hodges said.

However, students said that they’re more frustrated now with the way the situation was handled than the mold.

“I’m not mad about the hurricane,” Hodges said. “(The delayed remediation process) is a serious neglect towards not only the property, but also the people (they) were responsible for caring for.”

Madeline Taliancich is a senior at Loyola University New Orleans studying theatre arts and journalism who grew up just half an hour outside the wonderful...

Oliver Bennett is a mass communications journalism and sociology major from Dallas, Texas and Natchitoches, Louisiana. This semester, he’s excited to...

Kat Kelsey is a senior graphic design major and art history minor from Fort Lauderdale, Florida. She has contributed illustrations to the paper for the...