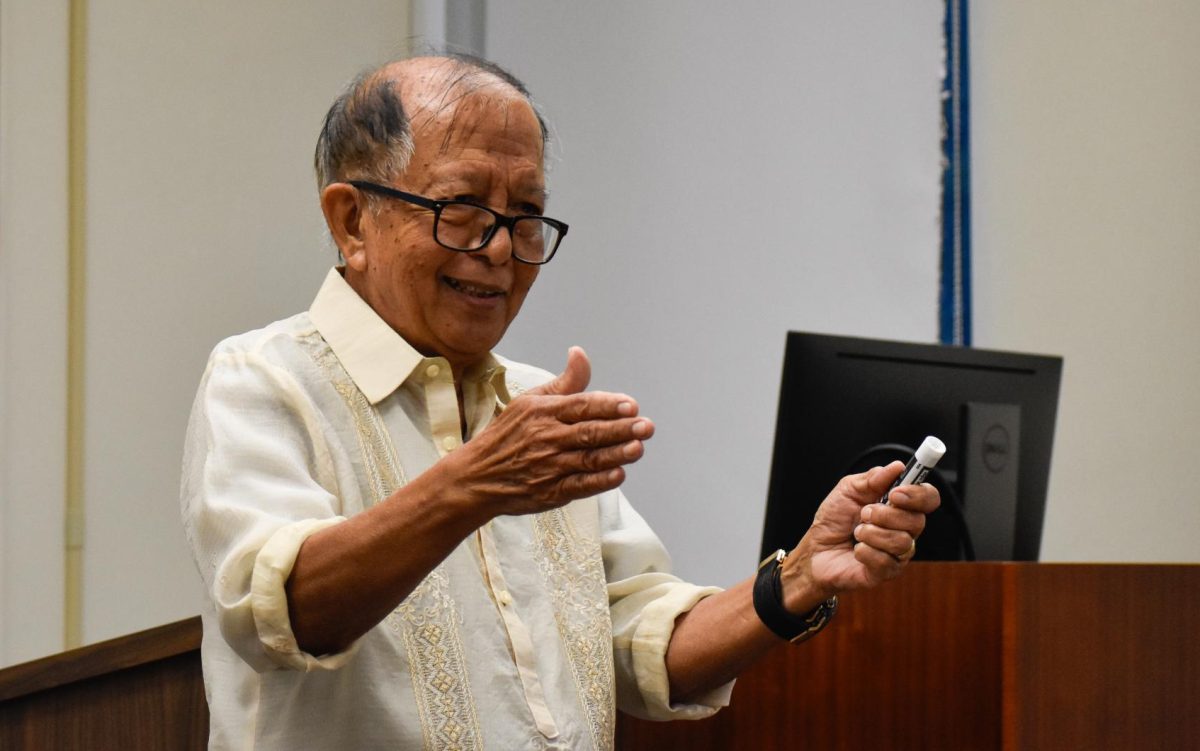

After being tortured in and exiled from the Philippines for his political activism, professor Alvaro Alcazar came to Loyola to foster a community driven by social justice. This was 38 years ago.

Since then, he has integrated the wisdom of his early-life experiences into his work, both in and out of the classroom. As a religious studies professor, he encourages students to take action against institutional injustices through what his students describe as non-traditional teaching methods.

While studying to become a priest in the late 1960s, Alcazar devoted himself to community organizing work in the slums of Manila, Philippines where he fought against Ferdinand Marcos’ dictatorship.

Marcos’ regime reacted to this work by detaining and torturing Alcazar and forcing him into exile from his homeland in 1972.

Soon after his exile, Alcazar arrived in the United States to continue his education.

Ever since then, Alcazar says he continues to ask himself, “how do I use the wisdom that came to me that I could not process as wisdom because I was too young?”

Alcazar’s experiences in the Philippines cemented his commitment to social justice activism through his faith. That commitment, he said, guides his service as a Loyola professor of religious studies.

“The in-fleshness of Jesus was something that my grandmother emphasized – that if you are given a symbol of bread, that it won’t ease your hunger,” Alcazar said. “The lesson that came to me was that I could not teach this poor community to pray if they are hungry, and that prayer is getting food, prayer is getting healthcare, prayer is sticking up to a dictator, that prayer is inconvenient, and prayer, because it’s inconvenient, is no shortcut.”

Alcazar began as the advisor to the Loyola University Community Action Program in 1985. Alcazar said at this time, LUCAP was primarily a charity organization.

During apartheid in South Africa, Alcazar led a boycott of Shell for economically supporting and supplying oil to the country. Eventually, this boycott gained the support of Loyola’s administration.

Alcazar taught in Loyola’s education department from 2001 until the discontinuation of the program in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina, leaving him without a job.

However, soon after, he was asked to join the Twomey Center for Peace through Justice as its Director for Urban Concerns.

“I persisted, and finally, Ted Quant, who was the director of a Twomey Center, said ‘Al, I need you here. I need your social justice orientation.’” Alcazar said.

Alcazar said he strived to continue the legacy of Fr. Twomey through his involvement in the Center, citing Twomey as spearheading efforts against institutional racism.

“Father Twomey was really ahead of his time,” Alcazar said. “It was Father Twomey that started opening Loyola to African Americans.”

Alcazar remained with the organization until its closure in 2017.

“It broke my heart, but at the time, the university was struggling,” he said.

Despite this initial disappointment, Alcazar said the Jesuit Social Research Institute is continuing the work and legacy of the Twomey Center.

“In the past, JSRI was a research group, and the Twomey Center was focused on action,” he stated. “That’s what the JSRI is leading to now. I was praying for it, that it would go that way, and I think it’s going that way.”

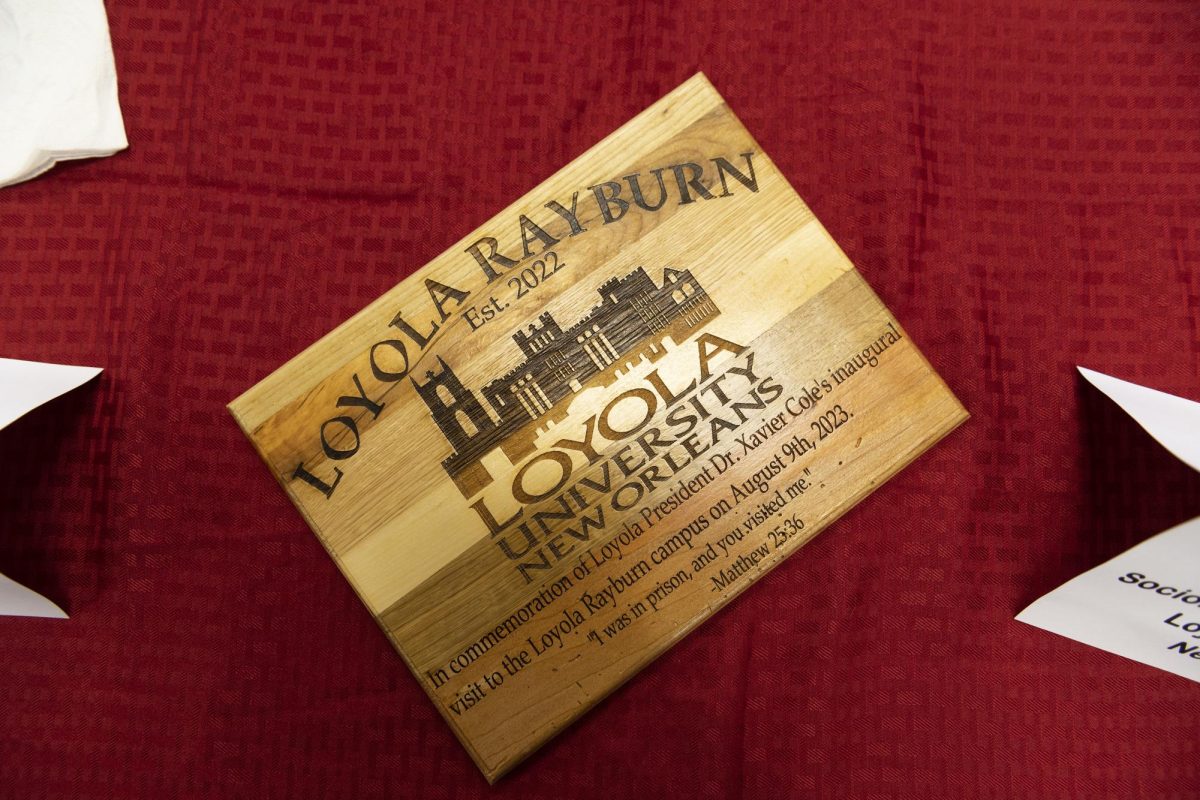

Alcazar said he is especially proud of the collaboration in 2022 between JSRI and the Sociology department in enabling incarcerated students at Rayburn Correctional Center to get their degrees through a prison education program.

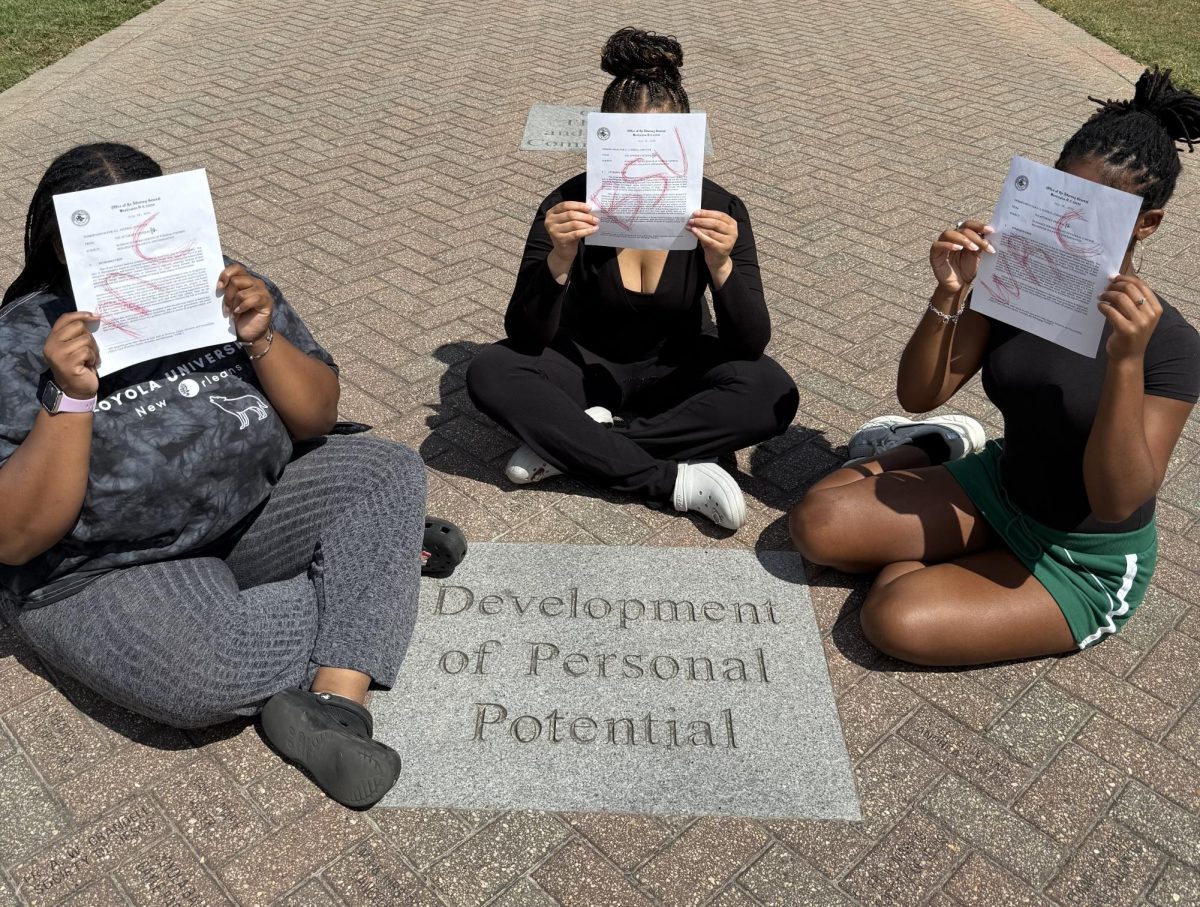

Alcazar said he has gotten in trouble with Loyola’s administration in the past for his protest leadership.

In particular, Alcazar mentioned his involvement in organizing a boycott in 1990 between Loyola and Tulane students over grape growers’ use of pesticides that were harming migrant harvesters. These grapes were used in the universities’ food service.

According to Alcazar, the protesters committed to blocking the door to the upstairs of the Danna Center and the Tulane president’s office door until Loyola’s administration joined the boycott and prohibited the grapes from the university food service.

In the end, the grape producers agreed to limit the spraying of pesticides to when the laborers would not be tending to the grapes.

Additionally, Alcazar said one Loyola president scrutinized him for organizing a protest in front of the home of Bob Moffett, the chair of Freeport-McMoRan, an oil company destroying an Indonesian village by pursuing oil resources. These protests drew national attention and coverage.

In this conflict with the president, Alcazar received support from his colleagues.

“But my boss, who was also a Jesuit, said, if you fire Al, you had to fire me as well, so he didn’t fire me,” Alcazar said.

With the Twomey Center, Alcazar led diversity training and conflict resolution teams in local schools. He said he created his “conflict escalator” model after witnessing a dispute over $5 between two high school students in the program.

“Conflict goes from annoyed or irritated to upset to angry to furious to enraged, and then it explodes, and people get hurt,” he said.

On Oct. 4 1984, on the Feast of St. Francis, Alcazar made a personal vow of nonviolence with Pax Christi, a Catholic peace organization, at Loyola after an encounter with a thief who wanted to steal his watch.

During this encounter, Alcazar said he had broken the thief’s rib and turned his knife on him, but something stopped him.

“I almost killed him. But something happened. I don’t know what happened, but I was told that’s how amazing grace works,” he said. “The words of [Martin Luther] King just thundered in my gut: ‘Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that.’”

He said he began implementing this vow into his training program while considering the use of nonviolent actions to address anger.

“I’ve shared this with my students, that you can come up with really practical things that you can do – some funny, some that would look weird – but that anything weird, anything funny replaces violence and hatred,” Alcazar said.

In his personal practice of nonviolence, Alcazar continues singing, playing guitar, and writing haiku to diffuse anger. He shares these methods in class by performing music and challenging students to write their own haikus about social and environmental justice.

Currently, Alcazar teaches Liberation Theology and Spirituality and Environment in Loyola’s religious studies department. In his teachings, Alcazar emphasizes an interfaith, spiritual approach to social, environmental, and political issues.

History freshman Gabriel Carver said Alcazar prompts students to analyze religious and government institutions through a critical lens and question the fundamentals of Christianity.

“[Alcazar] has really changed how I look at Catholicism,” Carver said. “As a religious person, you should be trying to change how the Catholic Church does things based on what you believe is correct.”

Nursing freshman Apolline BearChild said Alcazar has a “non-traditional” teaching style with a focus on anecdotal storytelling to convey themes of the class.

“He doesn’t try to force you to do things – he asks you, ‘What could you do for this? What are some ways you could try to make things better?’” Carver said. “It’s a refreshing thing to be asked.”

Alcazar’s Catholic upbringing informed these beliefs he shares in the classroom.

He witnessed negative aspects of Catholicism that were brought to the Philippines, particularly the erasure of his ancestors’ religion. This observation prompted him to seek spiritual education beyond the church.

Now, Alcazar considers himself both Catholic and Buddist.

“I think it is my interfaith orientation that has enabled me to connect with other people in ways that are meaningful, in ways that are spiritual but may not be religious,” he said.

Despite his persecution and forced departure from his home as a young adult, Alcazar has persisted in his mission of social justice and continues to share his unique perspective at Loyola.

Alcazar said he is proud of the impact he has had during his years at Loyola, especially through his student relationships, and he persists in his efforts to improve his community.

“[Loyola] has been a good place to work, but it’s not perfect, but that’s precisely why I’m here,” Alcazar said. “I believe in working in the system, within the system. And I think I’ve made some changes.”

Brian • Oct 25, 2023 at 9:57 pm

Hi Al,

Brian Jr., forwarded your enlightening article to me and first glance you look fantastic and aging well. You have accomplished some amazing milestones, overcome major obstacles, and crossed bridges that I never knew. Myself , the local and international community are grateful and appreciative for taking a stance for the good of many at risk of potentially losing your job and placing your life in jeopardy. I admire your brilliance and wisdom as a professor and educator but I think your bravery to bring attention to injustices and placing yourself on the front line is the ultimate call one makes for others. Happy the writer shared your story.

Thank you Mr. Alcazar

Ivey Sue • Oct 21, 2023 at 1:20 pm

Such an inspiring story, and beautifully written by Sophia Maxim.