As Louisiana prepared its first execution in 15 years, a team of lawyers from Loyola Law were working to save Jessie Hoffman’s life.

“I was a young lawyer three years out of law school, and Jessie was almost finished with his appeals at that time, and my boss told me we needed to file something for Jessie because he’s in danger of being executed,” Kappel said.

Kappel and her boss came up with a civil lawsuit to file that said since they wouldn’t give him a protocol for his execution, he was being deprived of due process, and the lawsuit was in the legal process for the next 10 years.

The state eventually dismissed the lawsuit, citing that they couldn’t get access to the necessary drugs to carry out an execution until an execution warrant was filed for Hoffman in February.

“A lot of people in Jessie’s situation have stuff going on in court for a long time, but for whatever reason, just bad luck I guess, he didn’t have anything going on or pending in court outside of the civil lawsuit we had filed,” Kappel said. “So I knew that he was at risk a lot more than anyone else on death row because of that.”

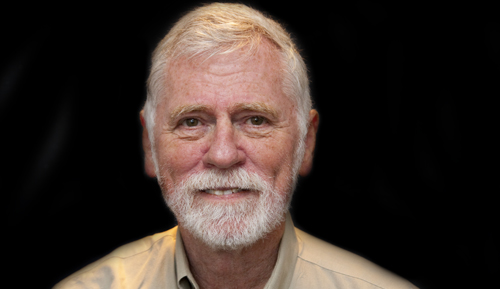

Emeritus Professor at Loyola Law Bill Quigley, who along with Kappel and three others, was able to see Hoffman the day of his execution, was also struck by the suddenness of the decision.

“No one was calling for executions to restart after 15 plus years. The Governor and Attorney General waited until after the Super Bowl and then announced they were pressing forward to execute three people,” Quigley said. “One was still in his rightful appeals process and that one was stopped. Another was already dying in the hospital and died before the state could murder him. So Jessie Hoffman was the only one left, and he was going to be the person.”

When she went to deliver the news, Kappel got a reaction she wasn’t expecting.

“I was really struck by how calm and how grounded he was in that moment,” she said. “He had a message for me that number one, he was okay, and number two, that he wanted to make sure that everyone else was okay. He wanted to make sure his family was good, his wife, and his child, and he wanted to enjoy every minute he had left. That’s how he was.”

For Quigley, the logic behind the decision had nothing to do with Hoffman at all.

“The victims were not asking for this murder,” he said. “The Governor and AG kept saying in talking points that they were murdering Jessie Hoffman for the victims. The facts show that is not true.”

A take that Kappel agreed with.

“This was not for the victims,” she said. “This was a political move by Jeff Landry and his people. He has been trying to execute somebody for 10 years, and he finally got his chance. And it wasn’t about, you know, what’s good for the family, or the prison staff, because it only hurt all of those people.”

The order for execution also came after Hoffman had been denied the chance to meet the family of the victim, according to Quigley.

“Jessie Hoffman committed a brutal senseless murder,” he said. “But he was remorseful and tried repeatedly to express that to the victims and it was the State that barred him from doing that.”

Leading up to the day of execution, Kappel often found herself overwhelmed by the situation she found herself in.

“It was… terrifying,” she said. “We tried to make a plan, then we had a plan, but unfortunately, the system is rigged, and it wasn’t in our favor. I tried really hard not to cry around him, because he said he wasn’t having that and didn’t want me to. He wanted us to fight for him until the very end and not give up, but he also didn’t want anyone’s pity.”

When the day came, Kappel said she saw a change in Hoffman as he reckoned with what was about to take place.

“Jessie actually kept us all grounded throughout this process,” she said. “But he was really angry leading up to it because he said he had been fasting for 2 days, but the guards weren’t letting him eat anyway. That kind of pissed him off.”

In the midst of that moment however, Quigley said, Hoffman was able to lean on his religious conviction for comfort.

“Jessie was a practicing Buddhist,” he said. “At the end he was praying along with readings from Thich Nat Hanh on love, kindness, compassion, joy and equanimity.”

That was a significant moment for Kappel, and served as a lasting reminder of the man she knew him to be.

“He had a right to be angry, because he was about to be murdered by the state, but he was able to just kind of release it,” she said. “It was kind of amazing to see because, obviously I wasn’t feeling anywhere near calm myself, but I tried to channel my inner Jessie.”

That evening, Hoffman was executed by way of nitrogen hypoxia, making him the first person in the state to be executed in that way, and the second in the nation after the state of Alabama executed Kenneth Eugene Smith using the method in 2024.

Hoffman’s execution occurred despite numerous attempts to ask for a stay of execution, or protest the execution entirely, both by the public and from his defense team.and according to Kappel, capped a whirlwind of a month for everyone involved.

“The people that were tasked with killing Jessie are the same people that were tasked with keeping him safe and caring for him in prison for all those years,” she said. “They announced that they wanted to kill Jessie on Feb. 10, and he was gone by March 18. It happened that fast.”

Kappel is choosing to use this moment as a guiding experience for her, one that drives her to make sure what happened to Hoffman doesn’t happen to anyone else.

“Experiences like these create a tidal wave of harm,” she said. “And it showed me that we have to be ready at all times for what could come next. Because Jeff Landry and Liz Murrill could just decide that they want to kill someone, and they can just do it. So we have to be building everyone’s cases up immediately to try and be better prepared for this and prevent another tragedy like this from happening again.”