The sound and shape of evil are elusive ones. A common refrain whenever a horrific event happens nowadays is, “They never seemed like they were capable of (insert horrific act).” And it seems to be something that is so perplexing that we search high and low for answers about how people can be complicit and partake in stomach-churning actions when everything about them appears so mundane and matter of fact. The nature of complicity and the capacity for evil is the subject matter that Jonathan Glazer exceptionally and chillingly examines in his newest feature film, “The Zone of Interest.”

The film, set in 1943, follows the lives of Nazi Commandant Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), and their children as they settle into their new home right next to the Auschwitz concentration camp. As the film progresses, the daily lives of the Höss family is shown in great detail ranging from their recreational activities, the parties they host at their new home, the gardens they tend to, and Rudolf’s careerism which causes marital difficulties between him and Hedwig. This all occurs while, obfuscated by a giant cement partition, smoke billows nonstop from the chimneys of Auschwitz and the steam of trains arriving incessantly at the camp rise over the tree line.

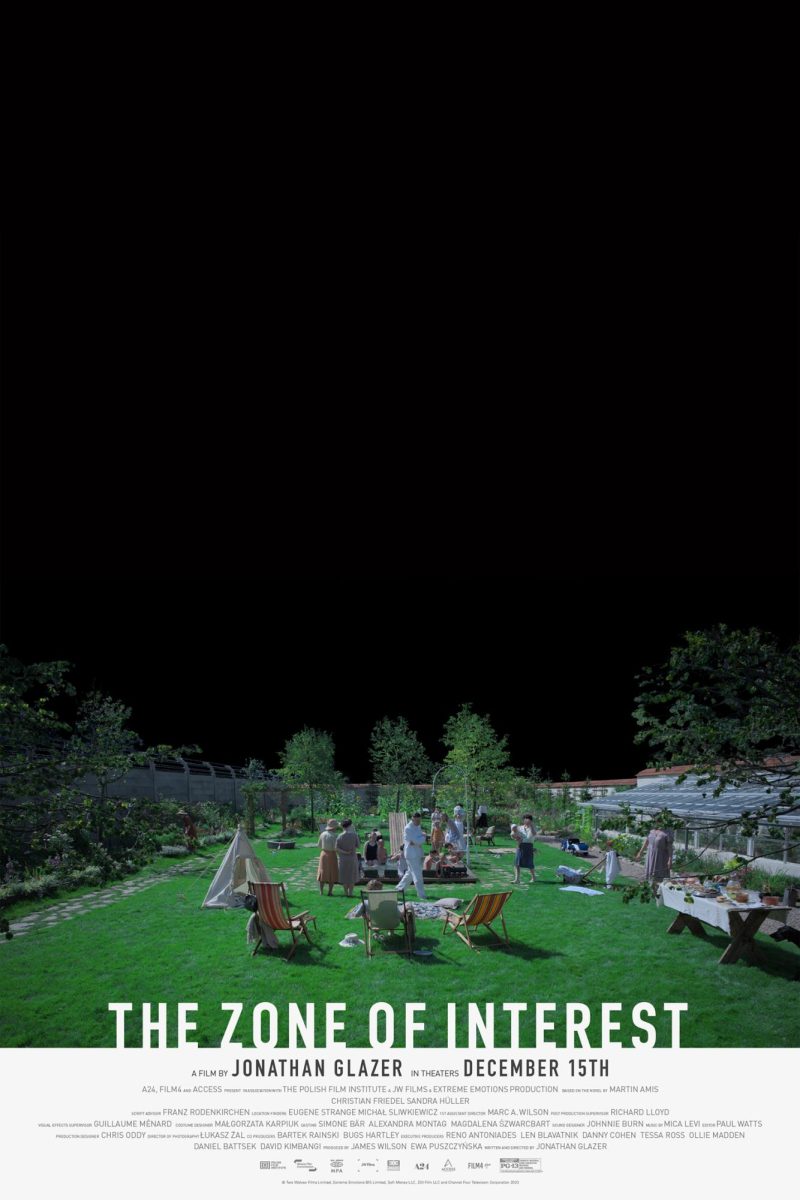

“The Zone of Interest” is a slow film that opts for a glacial pace in order to not only show the mundanity of the lives of the Höss family but also their ability to act blissfully unaware or down right apathetic of the horrors taking place just next to their home. This film is a genuine horror film masquerading as a thriller with the major caveat being that all the brutality and vile actions occur around the edges of the frame. In the same way that the Höss family is willing to push the horror aside to live their life the viewer is forced to see the atrocities tucked away at the edges in order to truly understand the complicity with which this family lived and benefited from the torture and extermination of others. This film examines the horror that takes place in silence and the people who willfully indulge in such silence.

These themes are handled with technical excellence through the cinematography of Łukasz Żal and the sound design of Mica Levi. The idea previously mentioned in this review regarding “tucking away” the horrors of Auschwitz is represented incredibly well through Żal’s visuals which place an emphasis on the focal point of shots and are composed in a way that puts the horizon at the top of the screen so as to draw the viewer’s eye away from the “family drama” elements of the film and asks that the viewer bear witness to the brutality occuring at the edges of the frame. The cinematography excels thanks to Żal’s simple yet effective shot composition which works in conjunction with the narrative to draw the viewer in and,in a way, ask that the viewer do what the Höss family is unwilling to do. Very rarely does Żal use close ups, perhaps a conscious decision meant to reflect the unwillingness of some to truly examine the nature of their actions or look closely at just what exactly they are complicit in. Żal’s subtle camerawork and shot composition is a premium example of politically conscious visual storytelling and the film is made infinitely more harrowing and engaging as a result.

Similarly, English musician Mica Levi does a fantastic job not burgeoning the film with any sort of unnecessary melodramatic score but rather allows for a large period of silence and natural noise to fill the scene before crescendoing in transitions that are both jarring and deeply unnerving. Large crescendos of booming bass work in chilling conjunction with Żal’s night time sequences that opt for a black and white night-vision display, creating an underlying sense of dread and a greater sense of hunter vs hunted.

The dialogue of the film is sparse but present with each interaction between characters, revealing their internal schemas. This allows them to go about their day to day lives in a way that is not really a deluge of information but rather a slow trickling out of the characters’ psyches. Christian Friedel and Sandra Hüller are exquisite in their performances, with Friedel perfectly embodying a careerist everyman who goes about his work with ruthless banality and Hüller embodying a housewife whose desire for security and status ultimately outweighs her conscience and empathy to a disturbing end.

“The Zone of Interest” is an impeccable, disturbing, and engaging film. But what’s most astonishing about it is that it is clear that Jonathan Glazer and all who were involved with the film weren’t interested in making a saccharine melodrama that exploits the horrors of the Holocaust like “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas,” but genuinely wanted to examine how individuals can be complicit in systems of violence and oppression even when the result of their complicity is endless suffering and death. Glazer is probing for the “How” and “Why” of people’s capability for banality and complicity in the face of evil as well as how this behavior is echoed in the 21st century. There is no film more incredible and timely than “The Zone of Interest,” a film which demands to be seen for the sake of the world we live in and for the sake of those who are still suffering as a result of our banality and complicity in systems that would rather horror go on in silence.

“The Zone of Interest” is showing in some select theaters and is nominated for Best Picture at the 96th Academy Awards.

5/5 stars.