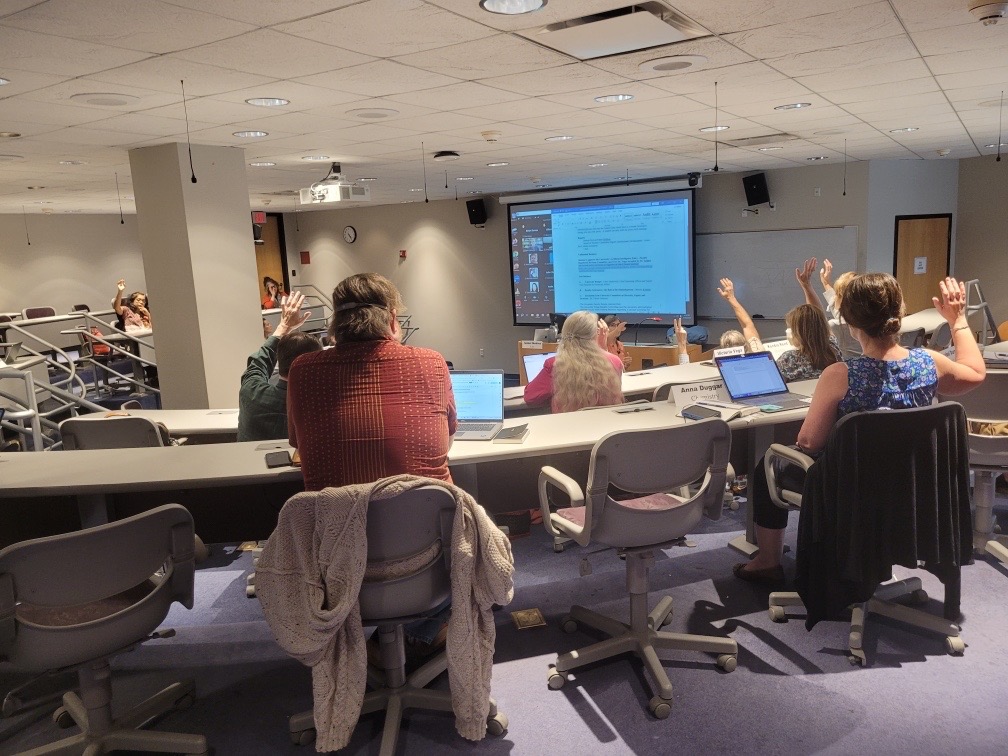

The university senate voted to endorse a new AI policy at Loyola. The policy outlines guidelines for students and faculty to follow in regards to the use of artificial intelligence in coursework.

AI has become an increasingly important conversation in academic settings, where it is becoming common for students to access content and information on any subject they may need.

Loyola’s new policy specifically focuses on generative AI, which has the ability to provide its users with original content like essays, emails, and articles.

The new guidelines, which were voted upon on April 14, allows students to practice the use of AI to promote idea generation and assistance in research.

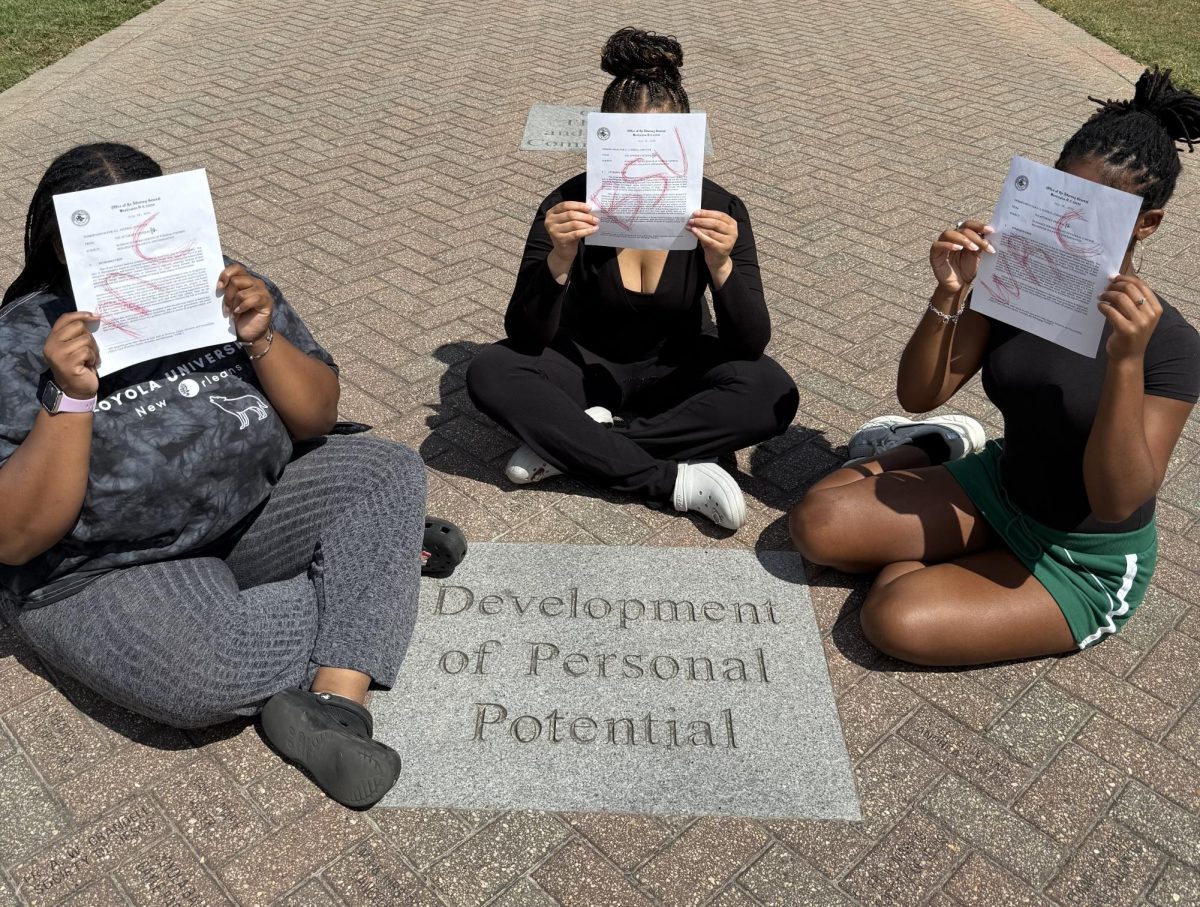

However, if a student attempts to submit work that was generated by AI as their own, it may result in the student’s violation of the academic honor code.

The new AI policy is subject to change and will be open for review every two years in order to stay up to date with new technological advancements and ethical standards.

Before the establishment of this new policy, no other like it had existed campus-wide for students and faculty to follow.

Some faculty at Loyola are welcoming to the new policy, and believe that these new frameworks can be useful in ensuring that students are properly fostering their education.

Classics professor Simon Whedbee believes that it is time well spent reflecting on how students can use AI effectively without compromising reaching the learning objectives of their courses.

“I’m glad to see that we’re working to educate our community on how these tools can be used well and what would constitute inappropriate use,” Whedbee said.

Whedbee feels that it is imperative that students use AI as a tool to grow, rather than as a means to complete work.

“The danger of AI in education is that it undermines the growth mindset,” Whedbee said. “If we lose sight of the fact that our schoolwork is supposed to foster our developing of skills that will be widely applicable elsewhere in life, then overuse of AI will leave us with good grades but without the ability to work without, around, or beyond AI capabilities.”

Other professors are open to the new technology, going so far as to implement the use of AI for research and planning purposes in their classroom.

Frankie J. Weinberg, associate professor of management, said that he has on occasion demonstrated or instructed students to use AI as a part of their research processes for projects and assignments.

Weinberg was the first professor in the College of Business to institute a student use of AI policy in his class. This same policy was then distributed by the College of Business Dean’s Office to other professors, as a suggestion on how they should regulate AI usage in their own classrooms.

Weinberg is a fan of the new policy but anticipates that AI and its capabilities may progress faster than the new policy can keep up.

“Anyone can see how rapidly AI has progressed over a much shorter period of time than that in a way that allows novice users to create projects well beyond the scope of what we could have imagined two years ago,” Weinberg said. “Therefore, I believe that the policy itself should be considered dynamic and have the flexibility to flux with the ebbs and flows of technological change more readily than that.”

Many Loyola students are accepting of the new policy and believe that it can be used as a tool to aid students who may be running low on ideas.

Graphic design sophomore Cadence Kempf said that she has used AI in some of her classes to create slogans, come up with titles, and generate ideas for essays.

Kempf sees the benefits of the policy and its ability to help students at times when they need a little extra assistance on their work.

“I’m all for the new policy, only because this is a resource to help students,” Kempf said. “Especially when you are burned out or have a lack of creative drive. Sometimes I just don’t have the energy. And I need help. I don’t see a problem with that.”

Other students feel that artificial intelligence in the academic setting can produce more trouble than it can solve.

English freshman Kaitlyn Gress believes that the use of policies and AI detectors can oftentimes flag students for the use of AI in situations where it is unwarranted.

“I don’t like how the use of AI has changed academic policies. Even though I don’t use AI to complete my assignments, I’ve still had an experience where something I turned in was detected by AI,” Gress said. “It was a very frustrating experience, and I ended up doing more work because of it, so I’m not too fond of AI.”

Guidance and clarity is an end goal shared by both faculty and students when it comes to the new policy.

Sarah Allison, director of composition and member of the university senate executive committee, said this basic agreement requires transparency about what work is getting done and whose work is being assessed.

“I have only one life on this earth and would hate to use it giving Cs to the collective wisdom of the internet applied to nineteenth-century novels,” Allison said.

According to Vice Provost and policy author Erin Dupuis, the policy can officially be approved once it has been looked over by one or two more members of the university senate.