When he talks, gone is his Southern drawl, replaced with a Dutch accent. The New Orleans native has lost his indigenous tongue. His E’s sound more like A’s. When asked about an old teammate, he describes him as “very hip” but says “vahry heep.”

It’s a phenomenon that his friends and family can’t believe. Still, others would say more unbelievable is his legacy.

His is a legacy that includes an individual scoring record 53 points against Virginia Commonwealth, second all-time scoring career points (which he did in just three years) and putting a whipping on six-time NBA All-Star Artis Gilmore.

He’s soft-spoken and sounds hardly like the mythological creature of his past, known by some as the greatest pure shooter.

His former coach, an NBA scout, said he had the best hook shot in the game, period. Even better than Kareem Abdul-Jabar’s.

Thirty-six years removed from his Big Easy birthplace, he’s lived his whole life away from home – away from his country – a 25-year pro career where he was first noticed in a warehouse-turned-basketball-gymnasium known as the Loyola Field House.

TREE THE SUPERHERO

“I remember reading about a 90-pound weakling and thinking to myself, ‘I’m a 90-pound a weakling,'” Tyronne Marioneaux said.

The book was “Captain America,” which transformed the 6-foot-2 Steve Rogers from a “90-pound weakling” to a super soldier after ingesting a serum that gave the young man superhuman strength to combat American enemies.

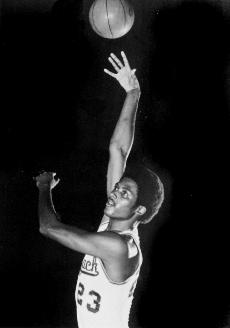

In a lot of ways, Marioneaux was like Captain America. His superhero name was “Tree,” because as former Maroon sports editor Bob Marshall described, “He was tall as a tree and had arms like branches.”

Marioneaux used his 6-foot-11 frame and branch-like wingspan to produce a hook shot that not even his villains could stop – namely, 7-foot-2 Artis Gilmore, known by his superhero pseudonym “A-train,” and in some circles, “Batman.”

But Marioneaux preferred to read about superheroes than play one. He wasn’t a gym rat. He read comics and played chess instead. He left the hustle to teammate Bobby Bissant, who once ripped a comic book from Tree’s branches on a flight to a game and shrieked, “What are you doing reading these funny books?”

He was odd, and most of his friends remember him as shy and distant from the rest. So distant that even his own alma mater doesn’t have any contact record of him.

ORIGIN

When you’re that tall, it’s hard not to play basketball. As Marioneaux recollects, he was forced into the sport.

One fall day in junior high school, a gym teacher sized him up. The man asked Marioneaux how tall he was. “6-foot-4,” Marioneaux replied. The gym teacher blurted out, “Boy, you ain’t no six-four.”

As it turned out, Marioneaux had grown four inches during the summer and now stood at 6-foot-8, a height that couldn’t be ignored at his age.

“I was kind of forced into it. It was expected of you.”

His unusual height didn’t come without teasing by his peers, but the ever-so-odd Marioneaux found the teasing funny.

“Once, someone made a joke like they asked me how old I was. When I said 13, he said he didn’t ask for my shoe size, and I laughed. I thought it was funny.”

Perhaps it was because the teasing didn’t have an effect on Marioneaux, or that he became more recognizable as a dominant force on the court, that the teasing stopped and Marioneaux became known as the ‘big man on campus.’

The University of Albuquerque first recruited The Walter L. Cohen High School product, but when offered the opportunity to stay within his comfort zone of New Orleans, he signed with Loyola.

“I preferred to stay home. I was pretty shy and didn’t want to start any journey.”

But Marioneaux was beginning a journey that would travel the country, facing the top college teams and getting recognized by pro scouts and settling for a European career 4,814 miles away in the Netherlands.

HOME COURT ADVANTAGE

The Field House was loved by the home team and hated by opponents.

Home of Loyola’s basketball program and the American Basketball Association’s New Orleans Buccaneers for three years, the Field House included an elevated court. The legend varies as to how high the court was, elevated some as high as four feet or as little as two, depending on the account.

“This was back when elevated courts were the rage,” Marshall said. “It was elevated so that when you were in the press box, your head was as high as the court and you watched their feet.”

Marioneaux’s earliest memory of entering the famed gymnasium was the feeling that overcame him.

“I liked the Field House. I liked seeing the coach sitting up from the chairs. I felt big time.”

The elevated court created havoc on the opponents who weren’t acclimated to it.

“If you were to dive for a looseball you might go right into the scorers table,” said head coach Bob Luksta, “but it was never a concern for us.”

“We were good for about eight or nine points on the other team,” said point guard Bobby Bissant.

It was in the Field House that Marioneaux had some his most memorable performances.

He set a record 27 straight free throws. He led his team to wins over Hawaii, South Alabama, Houston and Murray State, where he torched the Racers for 49 points. In his senior campaign, Marioneaux averaged 24.6 points per outing in the Wolfpack’s first winning season (16-10) in 13 years. The team averaged 92.1 points a game, the highest team scoring average in Loyola’s history till this day.

TAKING ON BATMAN

Marioneaux’s comic book tale would come to fruition in his second season with the Wolfpack. They took on what was then known as “the tallest team in the country”: Jacksonville.

Nicknamed Batman and Robin, the Jacksonville duo of Gilmore and Rex Morgan, an All-American, had destroyed every opponent leading up to that game.

“When I came into the game, I didn’t expect much. I thought I would be overwhelmed,” Marioneaux said of facing a No. 7-ranked team that eventually went on to the NCAA National Championship game before losing to UCLA.

The result: “Marioneaux outplayed (Gilmore) to pieces,” Coach Luksta said.

“For some reason, I didn’t think I would do anything,” Marioneaux reflected. “But I was getting rebounds, making shots – everything went perfect. It just seemed I was at the right place at the right time.”

The game, as Luksta recalls, was close to the final minutes with Loyola trailing by four or six points with five minutes to go. Then Charlie Jones fouled out, enabling the Wolfpack to double-team Gilmore and Jacksonville and clinching the game in the final minutes 96-75.

But the game didn’t end without Marioneaux hitting a buzzer-beating hook shot over Batman.

Marioneaux can still picture it. Facing the basket, squared with the clock ticking its last count, he saw a “really determined” Gilmore reach to the gymnasium rafters, but Marioneaux’s shot was a little higher. With a perfect arch, it landed just above the backboard square and banked into the net.

The final bucket didn’t determine the game’s outcome, but it did give Marioneaux more total points than Gilmore, and national attention ensued.

The Wolfpack were the first team to keep Jacksonville under 100 points and the formidable tale of Tree and A-train made Sports Illustrated.

“(Gilmore) didn’t like it. When it came out in the paper that I outscored and out-rebounded him, he made a vendetta and he was determined the next time they played, he was gonna make it pretty clear who was the better player.”

The game established Marioneaux as one of the premier big men in the country with a hook shot that made people take notice.

“Ty developed to be the very best hook shooter that I have coached or even seen,” said Luksta, who also served as an NBA scout for the Bulls, Magic and 76ers. “He shot six hook shots from every point. (Abdul-Jabar) might beat him on the (baseline) but Ty would beat him in every other spot because he could shoot with his left hand with equal skill, and it’s because of that I say no one can approach him.”

FOLLOW THE LEADER

While Marioneaux served as a leading role on the court, outside of the baselines he took the role of follower.

Like the time he followed his teammates into the locker room and hid while the gym was cleared. The team waited hours to avoid paying the entrance fee of a screening. The date was March 9, 1971, and on the The Field House’s projector screen was the first contest between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier known as “The Fight of the Century.”

As people gathered into the gymnasium, the players slowly filed out of the locker room and won free admission.

There was also the time Marioneaux stayed behind with teammate Charlie Jones at the airport, while awaiting their flight to Detroit to participate in the Motor City Tournament.

Marioneaux pleaded with Jones to go to the terminal, but Jones, with a mouthful of food, persuaded him to stay.

The team boarded the plane without their frontcourt. Trainer Tiny Tuneus alerted coach Luksta of the player’s absence.

“Tuneus says, ‘Coach, Tyronne and Charles aren’t here.’ I said, ‘Is the pilot here?’ And he said, ‘Yes,’ so I said let’s go.”

And the team left for Detroit with Marioneaux and Jones behind.

After settling into their hotel in Detroit, the phone rang in Luksta’s room.

“It was Tyronne and he said, ‘Coach, Charles and I are here,’ and I said, “Good.'”

Marioneaux replied, “Yeah, well, the cab driver is waiting to be paid.”

Luksta responded, “Well, who took the cab?” “We did.””Then you pay it.”

APPLE OF THE TREE

Perhaps what drew Marioneaux to comics was the bond he felt with these caricatures, who had Marioneaux’s near 7-foot frame and contradicting small feet. If Marioneaux was a tree, he’d be a palm tree – long and skinny in the middle.

“I was so skinny you could count every rib from 10 blocks away,” Marioneaux said.

And beyond his caricature-like outward appearance, his life could have been scribbled on a comic strip. He’d overcome a season-ending injury his freshman year, meeting face to face with Batman and Robin and later the “Houdini of the Hardwood.”

Marioneaux met the Houdini after his senior year at Loyola when he accepted an invitation to an NBA camp.

There stood the “Houdini of the Hardwood,” Bob Cousy.

Cousy was then coach of the Cincinnati Royals. He was looking for big men and Marioneaux was on Cousey’s radar.

The Boston Celtic legend and Hall of Fame member directed Marioneaux through a number of drills.

One drill, Marioneaux recalls, included a fast break play where he ran the entire court.

As Marioneaux approached the hoop, Cousy yelled, “Dunk!”

“I don’t even remember jumping – the next thing I know, I was looking down thinking that I had never been that high in my life.”

The following drive, Marioneaux darted to the basket, but with no command to dunk, Marioneaux lay-up the basket.

An enraged Cousy swatted the ball downward with such power it cut into his veins. Cousy had to leave the court and wore a patch around his wrists for the remainder of the camp.

Marioneaux never played for Cousy. The Denver Rockets drafted him, a feat he was unaware of till weeks after it happened when a complete stranger stopped him on the street and informed him.

He had missed the ride to Denver and decided to play overseas. He played two years in the Netherlands before his hook shot caught the eye of teams in Germany and Italy where he toured before landing back in Amsterdam, something he was grateful for.

“Everything looked funny in Germany, and Italy was great, but everyone only spoke Italian.

“In Holland, everything is English. The movies, all the programs are in English. It was pretty westernized to American standards.”

As his nickname followed him across the Atlantic, Tree’s career spanned three decades, before an ankle injury at the age of 46 that never healed correctly prevented him from continuing.

His comic book story isn’t anything like it once was. No longer is he active, nor is his main opponent “Batman” Gilmore.

He’s turned his attention and powers to coaching children ages 12 to 16, where Marioneaux serves as a talent developer preparing players for Amsterdam’s top league.

Oddly enough, it was the same sport he was forced into as a teenager that he made a career out of, then forced out of because of injuries.

But as Marioneaux would say, “I’m a strange guy.” Luksta would say he’s “Ty the Guy.” And basketball aficionados would describe him as the immortal guy.

With a six-year-old daughter who shows no interest in basketball, Marioneaux said “OK.” He won’t force her like he was forced.

No, she’ll find her own superpower.

Michael Nissman can be reached at [email protected].

Dan Uneken • Nov 15, 2022 at 4:14 am

Tree was a my trainer for a while in Amsterdam, in the early ’70s. He used to play along in practice and would shout “let it!!, let it!!” (meaning pass the ball, don’t hold on to it). It was a lot of fun and a great close-up glimpse of US basketball!