Loyola University New Orleans recently announced the accreditation of the Rayburn Correctional Center and is offering bachelor’s degree programs to more than 40 prisoners interested in earning their degrees.

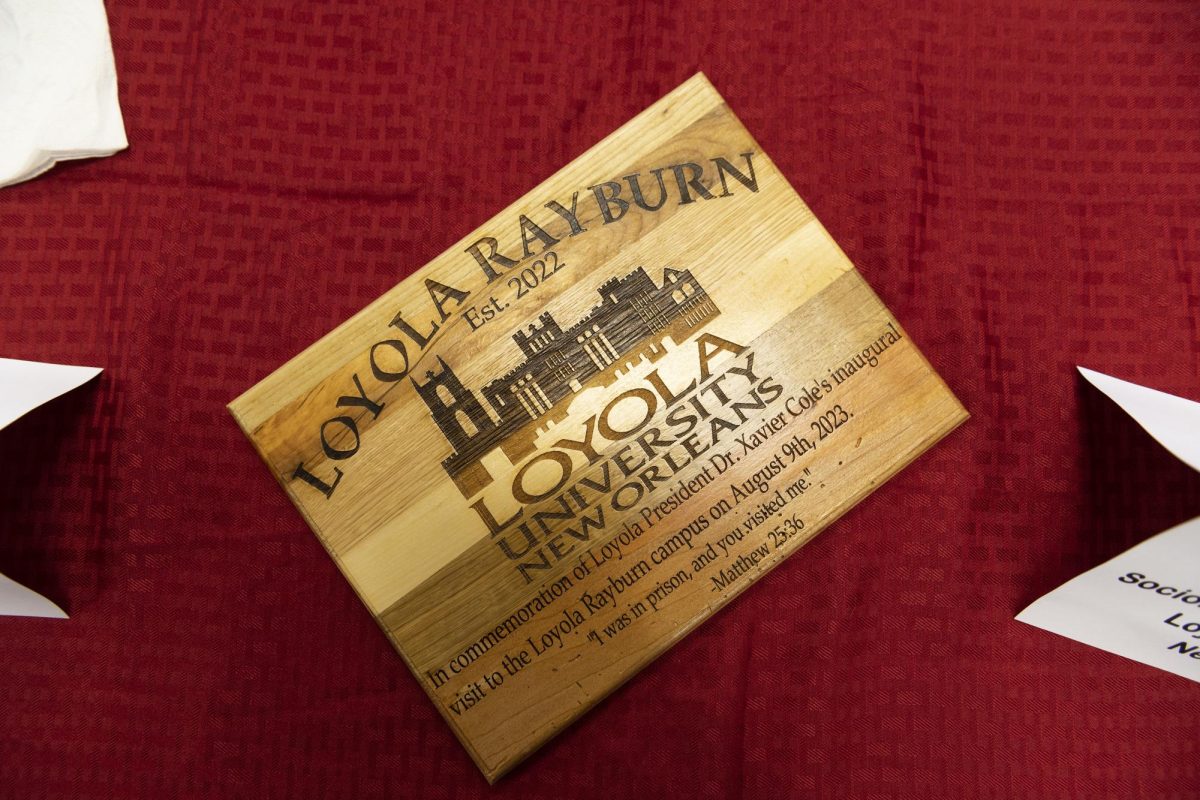

With the help of Annie Phoenix, Marcus Kondkar, Stephanie Gaskill, and Uriel Quesada, Loyola began its efforts to start a Prison Education Program at Rayburn Correctional Center. The program offered four credit classes in the fall of 2022 and earned accreditation on Aug. 1, 2024.

Stephanie Gaskill, the director of the program, explained that Loyola does not yet officially have a prison education program as defined by the U.S. Department of Education but the university is currently pursuing this status.

Higher education institutions across the country submit paperwork to open Prison Education Programs each year. While many of these requests are not approved by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges or require extensive revisions, Loyola’s program was clear in its submission to implement the program.

“We didn’t have to provide additional clarifications, and the Executive Committee of the SACSCOC Board of Trustees approved our proposal without concerns or objections,” said Quesada, who is the main liaison between SACSCOC and the university.

According to Uriel Quesada, Loyola’s SACSCOC liaison, when the program first began, more than 200 applications were submitted for just 20 spots. Due to the overwhelming interest among incarcerated individuals at Rayburn, the program now serves 40 students, and has a waitlist.

Quesada explained that the Rayburn students are part of Loyola’s Bachelor of Applied Science program, with two cohorts pursuing degrees in psychology and business management.

These students go through the same admissions process as any other applicant. However, they must have a high school diploma, write essays, and take an entrance exam to assess their existing knowledge. Many students enter the program with prior college experience, so their credits can be applied toward their Loyola degree.

Annie Phoenix, the executive director of the Jesuit Social Research Institute, said many of the incarcerated students did not have strong educational backgrounds before entering prison.

“To have this opportunity to go to school is a really meaningful thing for folks who maybe didn’t have a good experience,” she said.

Phoenix mentioned that while the Rayburn students are excited about the accreditation process, many also feared the program might disappear.

Gaskill and Phoenix emphasized that this is a true commitment from Loyola.

“It isn’t a project on the side,” Phoenix said.

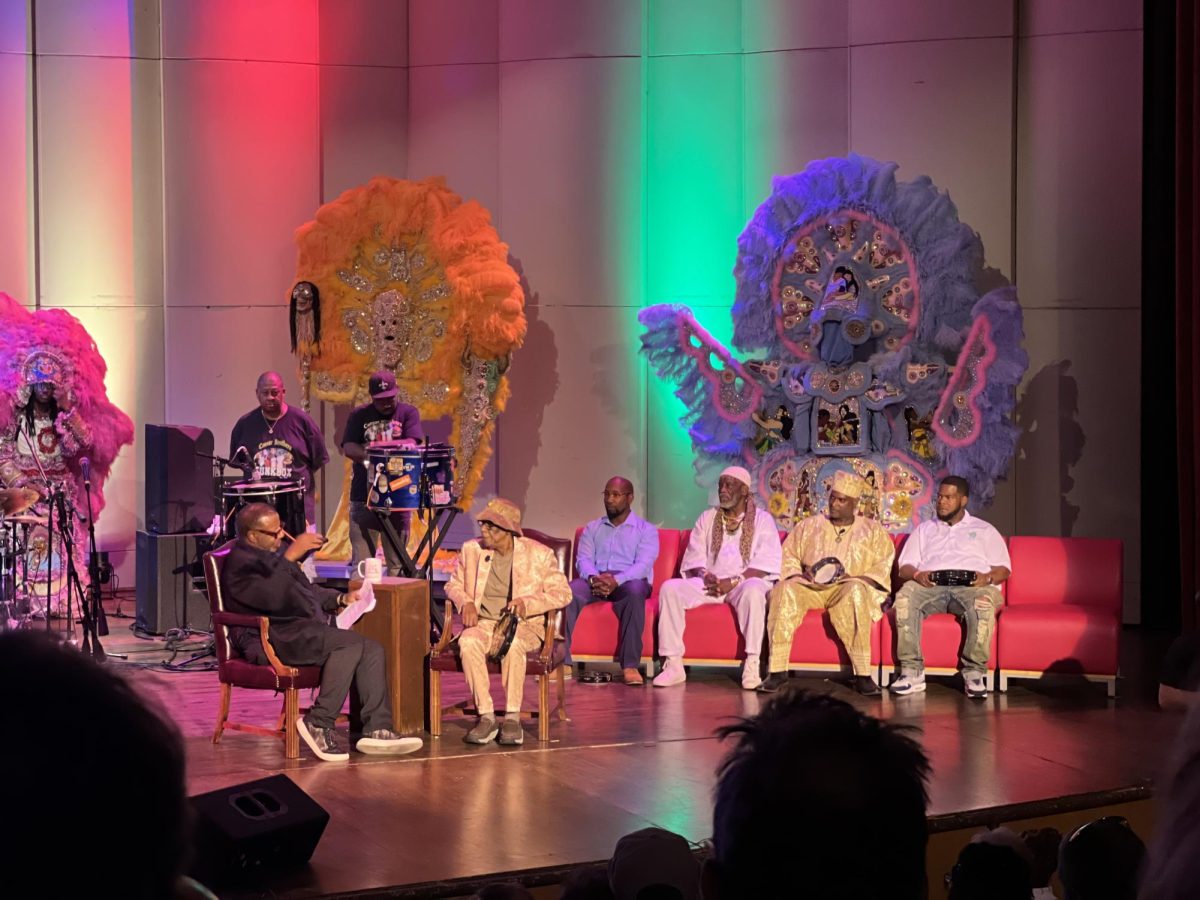

Participants in the program are made to feel part of the university just like students on campus.

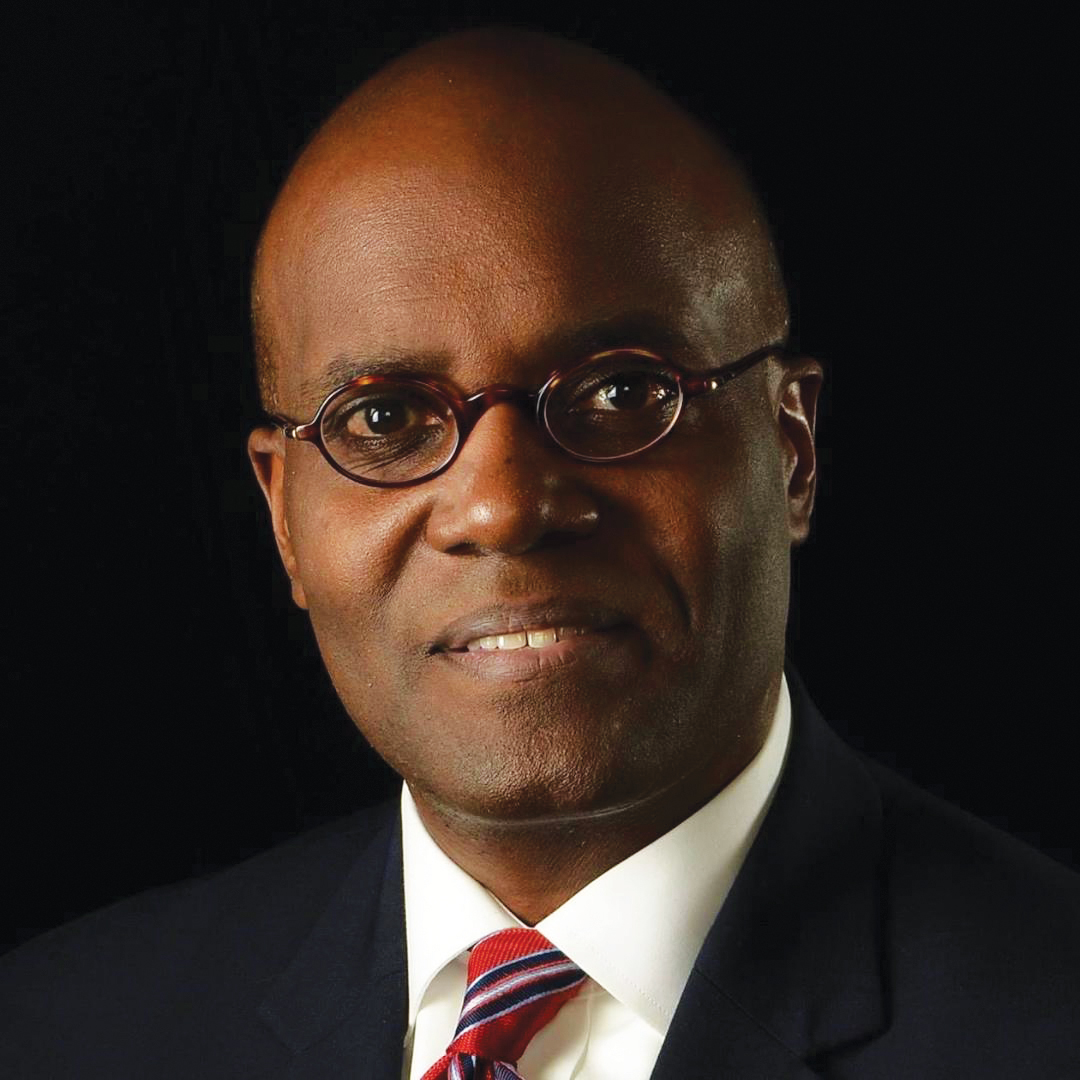

“When President Cole came to visit his new students, it just solidified that this is really happening for them,” Gaskill said.

Loyola’s mission is to provide education to students from diverse backgrounds so they can live meaningful lives.

Professor Gregory Lee said the students now have an anchor to a larger community, and when they graduate, they will have the identity of a Loyola graduate.

“A lot of these individuals are not going to be behind those walls forever, and gaining skills from a university like Loyola aligns with its social justice values,” Lee said.

According to Phoenix, the accreditation is opening more opportunities for site visits to the university and the prison, and the pursuit of Pell Grants for incarcerated students once the Prison Education Program is approved by the U.S. Department of Education.

It will allow for more classes and college prep courses to help students complete their degrees faster.

Gaskill and Phoenix urged students who want to get involved in similar programs to seek out professors doing this work, join student organizations, learn more about the topic, and take courses offered by the university.

“Education is about connecting with people,” Phoenix said.