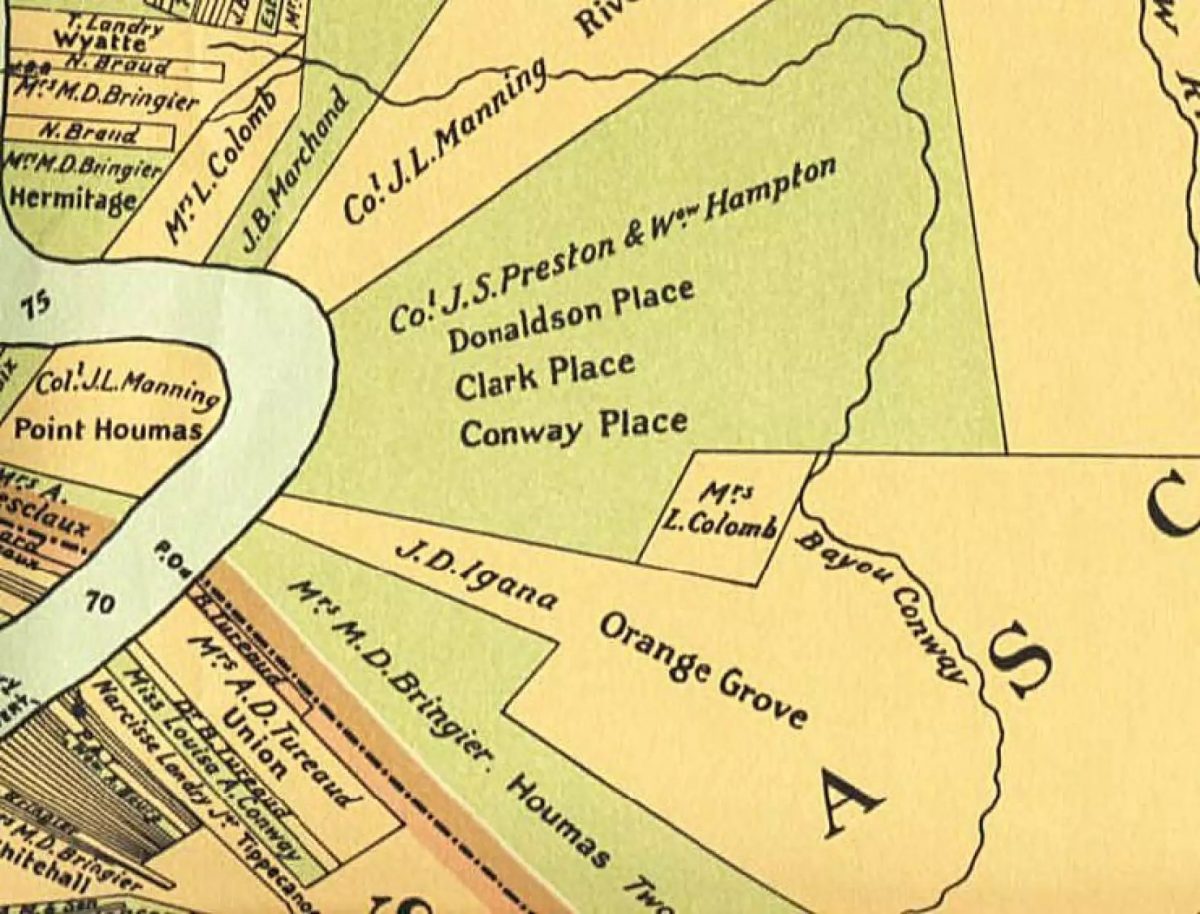

Chemical industry company Air Products plans to open a clean energy complex in Ascension Parish on the property of the Orange Grove Plantation, which endangers the burial sites of nearly 300 enslaved people.

RISE St. James, a local environmental group, is working to obtain a historical marker for the site, which will recognize it as a historically significant landmark, giving it official designations and legal protections.

In 2023, it was reported that Air Products found no evidence of burial grounds on the site beyond “scattered stones with illegible letters and numbers inscribed,” which were not determined to be graves, according to state archaeologist Charles McGimsey.

Student researcher and advocacy partner of RISE St. James Stephanie Oblena believes it’s not an issue of unawareness, but that economic gain is more important to state officials than history.

She said there is currently no federal or Louisiana law that explicitly protects burial grounds of enslaved people. While there were attempts made within the African American Burial Grounds Preservation Program, the bill was reduced to a grants program without authorizing an entity to identify, interpret, or preserve vulnerable sites and history.

Subsequently, Air Products has no legal obligation to reconsider the complex.

The global hydrogen supplier plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by 2050 through clean hydrogen projects and production.

According to Jim Schott, Loyola professor and electric utility and environmental professional, in order to achieve net-zero carbon emissions, the world has to move away from fossil fuels, like natural gas, petroleum, coal, and oil. This requires a transition to new energy sources, such as solar, wind, nuclear, and hydrogen – the linchpin of Air Products.

When hydrogen is combusted as a fuel, it has zero carbon emissions; however, hydrogen must be manufactured by refining natural gas. With today’s technology, the process of refining natural gas to create hydrogen creates enormous amounts of carbon dioxide, the primary greenhouse gas, according to Schott.

Air Products plans to eliminate this issue by manufacturing blue hydrogen, which calls for a similar process of refining natural gas. Instead of releasing CO2 into the air, it will be injected into underground geological structures, where it is sequestered forever.

According to Air Products, the project will sequester 5 million tons of CO2 per year.

While Air Products’ primary goal in producing blue hydrogen is to improve the sustainability performance in the Gulf Coast region, Oblena believes the facility will create “a reframed version of what we already see in Cancer Alley.”

Cancer Alley refers to the 85-mile stretch of communities between New Orleans and Baton Rouge that reside alongside nearly 200 fossil fuel and petrochemical plants that have caused devastating effects to the environment and a considerable increase in cancer, upper respiratory diseases, and other health risks for residents of the area.

Air Products would produce blue hydrogen at this Clean Energy Center and inject through their existing pipeline network that stretches from Galveston to New Orleans feeding into the southeast Texas hydrogen hub for use in energy and fertilizer markets, Schott said.

However, Oblena believes this will pose many risks to the community.

“Supposedly, this would be the largest and the first in Louisiana, which sounds almost like a test run with Louisiana being an ideal site,” Oblena said. “The biggest risks are the amounts of highly concentrated toxic gases that will be handled in the complex, like methane. Regardless of where things are stored, leaks happen, and all of these substances impair human health.”

Oblena said a major concern of the project is the proximity to Sorrento Elementary School, which would be within two miles of the facility.

Schott said the Environmental Protection Agency and the state have laws and regulations that apply to any type of source of emissions, which are required to consider public health and welfare standards.

“Any industrial facility, or any human made structure, will have some impact on a surrounding community,” Schott said. “Air, water, noise, and light pollution are all relevant considerations in siting any facility.”

The EPA and the state require facilities to apply the latest technologies to prevent impacts on health and welfare, and the operating permits require monitoring, reporting, and compliance audits, he said.

Even with the proposed improvements the facility would provide, Oblena believes there are still harmful implications in disrupting the Orange Grove Plantation.

“Throughout all of the literature on cemetery sacredness and history, there is this emphasis on the importance of burial grounds as a ritual for human life and how it comes to an end,” Oblena said. “In the National Register of Historic Places Bulletin on Cemeteries, burial grounds have an ‘inviolate nature.’”

Oblena said the long-term goal of RISE St. James is for the Orange Grove Plantation to be recognized as a National Historic Landmark or listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but for now, they’re attempting to register it as a historic cemetery with expected deadlines for May.

To continue to help protect the sanctity of other vulnerable places, the organization is establishing the St. James Historic Preservation Committee, which consists of historians, archaeologists, and concerned community members. The organization will not only determine the next steps of preserving burial grounds but also tell the stories of the people buried there.

“The system and relationship of power is the same; the circumstances are just different,” Oblena said. “The fact that people who lived, labored, and died as human property are being disrespected in their burial is appalling.”